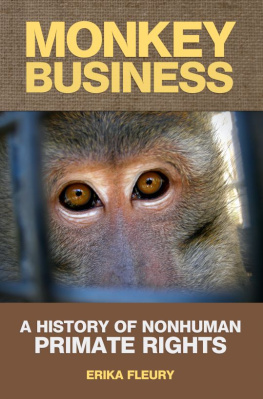

MonkeyBusiness

A Historyof

Nonhuman Primate Rights

ErikaFleury

MonkeyBusiness: A History of Nonhuman Primate Rights

ErikaFleury

Smashwordsedition

Copyright 2013, Erika Fleury

Cover photoused courtesy of Primate Rescue Center, KY.

SmashwordsEdition License Notes

This ebook islicensed for your personal enjoyment only. This ebook may not bere-sold or given away to other people. If you would like to sharethis book with another person, please purchase an additional copyfor each recipient. If youre reading this book and did notpurchase it, or it was not purchased for your use only, then pleasereturn to Smashwords.com and purchase your own copy. Thank you forrespecting the hard work of this author.

Library ofCongress Control Number: 2013910787

ISBN-13:978-1301679423

08042013v1

This book isdedicated to Grandma Ruth,

who would havebeen proud.

Contents

Preface

This book isdesigned to document progress that has been made in the strugglefor nonhuman primate rights. As I researched the subject, I learnedthat many early efforts to support a major causeor a fight forrights or protections for a grouphave been met not only with adefensive wall to hurdle but, even worse, with outright publicapathy. In this case, whenever I explained the concept of my book,I would hear over and over, Primate what? Primate rights?" Aftermaking a comparison with the animal rights movement (a differentbut related and much more well-known concept), I would then oftenbe asked what primates were. I knew I had important work ahead ofme.

It is my hopethat documenting the history of primate rights will make the causeeven more real and important. Earlier works have covered some ofthis material; however, recent changes to lawsand, thankfully, topublic opinion about the proper treatment of nonhumanprimatesencouraged me to write and collect this information intoone cohesive history. I wanted to assemble it as quickly aspossible, for I knew that the sooner I could get it out in theworldbound, printed, and ready to educate readersthe more quicklyour culture might progress toward legal freedom for our closestanimal relatives, the nonhuman primates.

ErikaFleury

Thank you to:

My family, forsupporting my dreams.

Those whodirectly helped to make this book a reality,including

(but notlimited to):

April Truittand the Primate Rescue Center, for giving me a chance andcontinuing to help me so many times in my travels throughoutthe world of primatology; my brother-in-law, Kyle Aaron, for hisamazing cover design talents; and my night-owl of an editor,Deanna Brady, for turning my book into something I would wantto read.

My daughter,the beautiful Leila Jaye Fleury,

for wiselydelaying her birth and allowing this book to be completed.

And mostly,thank you to my husband, Teague Fleury,

for alwaysinspiring me in our shared mission to protect little things.

PS: I have muchgratitude for the readers of this book. I look forward to yourinput and thoughts. Please visit me at www.authorerikafleury.blogspot.com for my news and contact information.

Prologue

"Blood isthicker than water," promises an old proverb, and the actions ofmost of us prove this to be true. People naturally place a highlevel of importance on the safety, happiness, and comfort of theirrelatives. It is generally understood that individuals are morelikely to value the overall quality of life of their kin above thewell being of absolute strangers.

Even in theanimal world, members of various species seem to know that certainother members are part of their extended family and, as such, aremore deserving of patience, favors, and protection from threats totheir welfare. This is how bloodlines are perpetuated. Livingcreatures have a Darwinian instinct to act in such a way as to bestpreserve themselves and their descendants. Without this drive,their offspring would not live long enough to reproduce, and thefamily line would die out.

When thispreservation instinct is acted upon, a species usually continues toevolve and grow ever more prosperous in its environment. As highernumbers of relatives survive and reproduce, families expand at anexponential rate. This means that, at some point, a thrivingbloodline could grow large enough that it would be difficult forits members to recognize some of their own more distantrelations.

How thin canblood become before it appears to be no more than water? Where dowe draw the line between family and the rest of the world? Is therea point at which we stop feeling connected to distant relatives?Certainly our mothers, grandfathers, aunts, and nephews are ourrelatives. What about their relatives by marriage or remarriage?What about second and third cousins? How do we consider theirchildren?

With eachdilution of the genetic bond to us, individuals will likely beconsidered less and less as family members. At a genetic distancethey will typically garner less of our sympathy and concern andseem less deserving of our protection.

Most humansocieties place a high value on human life. Cultures may assignlevels of inherent worth to specific human lives, depending on suchcharacteristics as race, gender, religion, ethnicity, behavior, andsexual orientation, but individuals and groups typically align andfeel united with those most like themselves. As a corollary to thistendency, humans tend to value human life over that of otherspecies. Past the dividing lines of family, friends, acquaintances,and strangers is a boundary where the human species abuts others,and humans generally consider that line to be sacrosanct.

Humanbeings are members of a vast and varied order of intelligent andhighly specialized animals known as primates. Considering thatthere are more than 230 other distinct species of primates,however, it becomes clear that human beings are but a blip on theprimate radar.

Despite thatminority status, we often refer to our closest relatives in thisorder as nonhuman primates, which is a way to define them as notlike us but which can be misleading in terms of the group as awhole. To refer to all other primates as nonhuman, simply in orderto separate them from the less than one percent of the primatepopulation that is human, is akin to referring to almost all applesas non Macintosh, when only a small fraction of the apple worldis actually of the Macintosh variety. In fact, this is only oneexample, among many, of the way humans categorize the worlds otherspecies in purely anthropocentric terms.

The best way toillustrate the biological relationships between humans and otherspecies is through the universally accepted system of ranking theliving world developed by Carl Linnaeus in the mid 1700s. TheLinnaean Classification System establishes distinct points at whichvarious groups of living beings branched off evolutionarily fromtheir common ancestors, with each branching producing anincreasingly distinctive group.

Each of thesebranches is delineated with a new category so that the path a givenspecies followed to evolve its particular traits can be traced. Forexample, the vast class Mammalia includes all mammals, andwithin this class resides the order Primates, to which belong themore than two hundred species of apes, monkeys, andprosimians. Moving down the primate chain a bit farther,through suborder Anthropoidea, infraorder Catarrhini, superfamilyHominoidea, and all the way through family Hominidae (greatapes) and subfamily Homininae, we reach the point at which thegenus Homo (human beings) finally separates from the otherprimates.

Within theprimate family, the genetics of humans are most similar to thebonobo (genus Pan and species paniscus), even more so than to thechimpanzee (genus Pan and species troglodytes). The genus namerefers to the Greek god Pan, a herder who had goat legs but thetorso of a man. The name may have been chosen for chimpanzees andbonobos in order to reflect how close they really are to humans.Seeming to have one foot in the animal kingdom and one in thehuman, chimpanzees and bonobos appear to be the missing linkbetween man and the rest of the natural world.