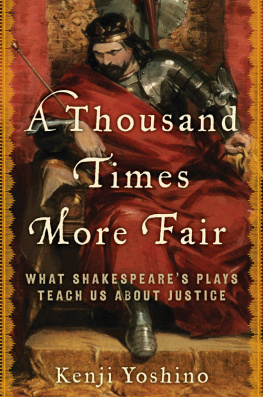

A Thousand Times More Fair

What Shakespeares Plays Teach Us About Justice

Kenji Yoshino

For Ron Stoneham

Thy lifes a miracle

Contents

The Avenger

Titus Andronicus

The Lawyer

The Merchant of Venice

The Judge

Measure for Measure

The Factfinder

Othello

The Sovereign

The Henriad

The Natural World

Macbeth

The Intellectual

Hamlet

The Madman

King Lear

The Magician

The Tempest

I initially attempted to write about Shakespeare and the law in my first year of law school, hot off an argument with my Constitutional Law professor. We were learning about stare decisis, the doctrine that legal precedents must be followed. My professor made an offhand remark about how law had a fundamentally different attitude toward originality than literature did. Put bluntly, law did not value originality. If a judge found a case essentially identical to the one he was deciding, he gained, rather than lost, authority by relying on it. In literature, he said, one did not gain authority by saying someone else had already made the point.

This contention piqued my curiosity because my major extracurricular activity in law school was wondering why I was there. As an undergraduate English major, I had seriously considered pursuing a career as a writer or literature professor. I chose law school because I wanted to acquire the language of power, for myself and for my causes. I had not realized how narrow or dry the texts of power would be. (I am not sure what I was expectingperhaps Prosperos grimoire, or book of magic.) So I was excited that a law professor was giving me an idea I could test against what I was sadly coming to think of as my prior literary life.

I pondered his claim for a few weeks before going to speak with him. After telling him that literary studies still felt like my native heath, I asked him if I could write a paper with him on theories of literary and legal precedent. I proposed to look at how literary works also drew strength from their canonical predecessors. A lifelong Shakespeare devotee, I had even chosen my texts. I planned to contrast the strategy Tom Stoppard used in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead to revise Hamlet (indirect subversion in which the later play changes the meaning of the prior one without contesting any of its facts) with the strategy Aim Csaire used in Une Tempte to revise The Tempest (direct subversion in which the later play rewrites the facts of its predecessor).

My professor attempted to dissuade me. He told me I was being trained to think like a lawyer. Confronted with a strange new discipline, I would find it natural to cling to my old one. But doing so would delay the necessary transition. He was not unsympathetic. He had been an English major himself, but had gone into law to addressI remember his neat phrasingjustice itself rather than justice represented in fiction. He was gentle about it, which I admired, not least because he had manifestly had this conversation many times before. But I received the clear message that my literary life was a thing of the past. It was time to put childish pastimes away, and to focus on my adult profession.

I do not think human beings are particularly plastic. A few weeks later, I was back in my professors office, saying I had thought hard about his advice, but that I still wanted to write the paper. To his eternal credit, he respected the set of my jaw and agreed to let me do so. The paper was my first publication in a law review. As legal scholarship, it was a failureI did not know enough law at the time. But it served its purpose. It fixed my conviction that I could and would always make a place for literature in my life in the law.

My focus as a law professor over the past twelve years has been on civil rights and constitutional law: justice itself rather than justice represented in fiction. I have come to love the law and have never seriously regretted my decision to pursue it. Nonetheless, I have also never stopped teaching classes on law and literature. I do not regard this as a vestige of my past. To the contrary, I use this class to keep steadily visible that the law itself is a set of storiestold by legislators and judges, plaintiffs and defendants. As the late law-and-literature scholar Robert Cover put it: for every constitution there is an epic, for each decalogue a scripture. We cannot understand the law unless we see how its formal texts are embedded in the narratives that accord them shape and meaning.

Some of my colleagues view my law-and-literature classes as soft or suspect, for many of the reasons that my original professor told me to surrender literature for law. In their view, literature is too different from law to illuminate it. Reading literature as a guide to legal decision making is, in Judge Richard Posners memorable phrase, like reading Animal Farm as a tract on farm management. Such criticism has its fiercest bite when I know the critic loves both literature and law but thinks the two practices do not enrich each other.

My students feel different. As of late, my Constitutional Law classes tend to be oversubscribed by a ratio of about two to one, but my Law and Literature classes are oversubscribed by a ratio of about six to one. These students know that literature will complete their legal educations. They get the formal legal texts every day. They miss the scriptures and the epics. I recognize my old self in their hunger, and I stand with them.

Over time, my general class on Law and Literature has morphed into a class on Justice in Shakespeare. I switched because I did not like flitting from author to author. Once I decided to focus on a single author, the choice was obvious. If I was going to teach the class under the canopy of one authors work, I wanted it to be, as Hamlet says, fretted with golden fire ( Hamlet, 2.2.267). As my first student foray into law and literature suggests, nothing makes me feel as I do when I read Shakespeare. To read Shakespeare is to feel encompassedthe plays contain practically every word I know, practically every character type I have ever met, and practically every idea I have ever had.

In writing this book, I am not relying on the claim that the author of the plays was, as Mark Twain argued, a lawyer. I believe Shakespeare knew a lot about the law, but only as a by-product of knowing a lot about everything. Freud was convinced Shakespeare had anticipated most major issues in psychoanalysis. I think Shakespeare got there first with respect to issues of social justice as well.

I do not have a definition of justice. I am drawn to literature rather than to philosophy because I would rather deal with the messy, fine-grained, gloriously idiosyncratic lives of human beings than with vaulting abstractions. At the same time, I think some cases illuminate timeless principles. For this reason, I have selected plays that raise these issues, making the contemporary links explicit where appropriate. I look at how Titus Andronicus illuminates our current engagements in Afghanistan and Iraq because it describes how revenge cycles escalate when no credible central authority exists. I look at how the white handkerchief in Othello can be compared to the black glove in the O. J. Simpson trial, as both forms of ocular proof wrongly overwhelmed all other evidence of guilt or innocence. I look at the Tempest as an exemplary instance of an omnipotent ruler voluntarily surrendering power as Cincinnatus did before him and George Washington did after him, asking who is willing to do that for us today.

Even Shakespeare cannot give us all the answers. I identify with James Joyces Leopold Bloom, who applied to the works of William Shakespeare more than once for the solution of difficult problems in imaginary or real life. Despite careful study, Bloom derived imperfect conviction from the text, the answers not bearing on all points. Shakespeare himself expressed skepticism about whether justice could be achieved through beauty: How with this rage shall beauty hold a plea, / Whose action is no stronger than a flower? (Sonnet 65, 34).

Next page