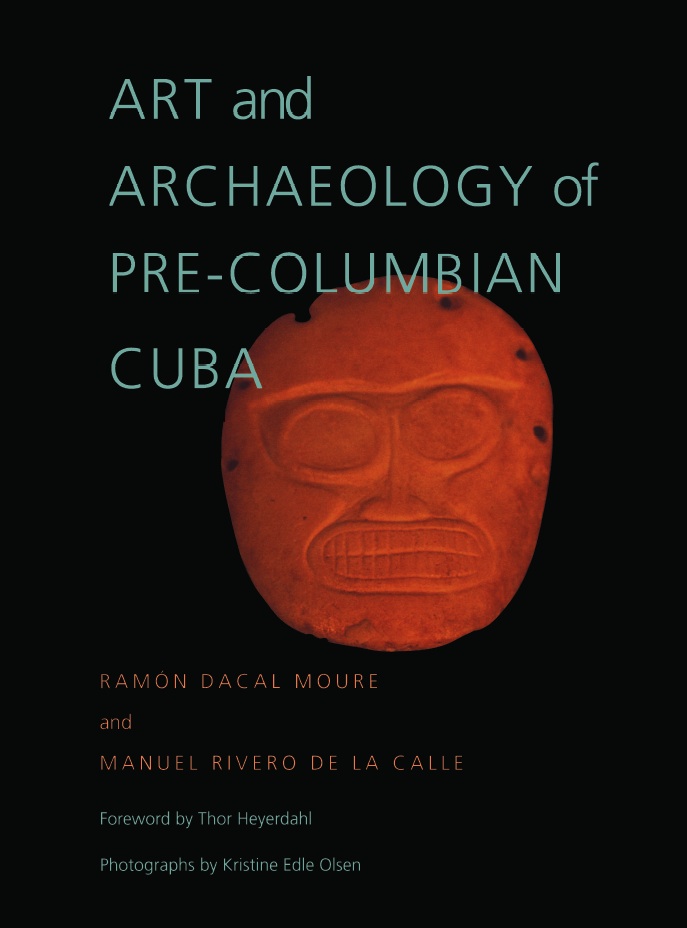

Published by the University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa. 15261, in cooperation with Ediciones Plaza, Havana

All photographs beginning on page 55 by Kristine Edle Olsen except as otherwise noted.

Dacal Moure, Ramon.

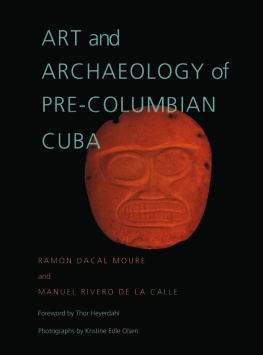

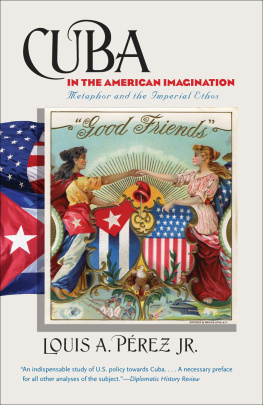

Art and archaeology of pre-Columbian Cuba / Ramon Dacal Moure and Manuel Rivero de la Calle ; translated by Daniel H. Sandweiss ; edited by Daniel H. Sandweiss and David R. Watters ; foreword by Thor Heyerdahl ; photographs by Kristine Edle Olsen.

p. cm.(Pitt Latin American series)

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

1. Taino art. 2. Taino IndiansAntiquities. 5. Excavations (Archaeology)Cuba. 6. CubaAntiquities. I. Rivero de la Calle, Manuel. II. Title. III. Series.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the Foundation for Explorations and Research on Cultural Origins (FERCO) in Tenerife for support that made this publication possible.

ABBREVIATIONS

CAC Collection of the Academy of Sciences, Center for Anthropology, Havana

GA Laboratory of Archaeology, Office of the Historian of the City of Havana

MAM Montan Anthropological Museum, University of Havana

MG Provincial Museum, Guantanamo

MIB Ban Indocuban Museum, Banes, Holgun Province

MM Mayar Museum, Holgun Province

MPH Holgun Provincial Museum, Holgun Province

MSCM Site Museum, Chorro de Mata

FOREWORD

THOR HEYERDAHL

Cuba plays a central part in the historic events of 1492, events that the world at large will forever recall as a milepost in human history. It was on this great mountainous island that Christopher Columbus landed when the first Americans received him in their homes. After passing through the small coral atolls of the Bahamas, Cuba was the first large land mass Columbus encountered in the New World.

Columbus had crossed the Atlantic Ocean with a letter of introduction from King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella to the Great Khan of the Orient, and he wasted no time on the sandy atolls in the Bahamas. He was heading for Cipango (Japan) and Cathay (China), and the very day after reaching the first little atoll he pushed on, writing in his diary: In order not to lose time I intend to go and see if I can find the island of Cipango. Two weeks later, on 27 October 1492, he reached Cuba, and now his reaction was different. He wrote: Truly, I was so astonished at the sight of so much beauty that I know not to express myself.

These were strong words from the pen of an experienced explorer who was familiar with the most beautiful coasts of the Mediterranean and West Africa, the Canary Islands, and even Madeira and the Azores. Columbus came to Cuba on all but the third of his four trans-Atlantic voyages. And on his second visit he was already so desperate at not living up to his promises to find a shortcut to the riches of the Orient for the sovereigns of Spain that he called all his shipmates together and made them swear that Cuba was a continent and not an island.

Despite the controversy that began when admirers of Columbus decided to prepare the quincentennial celebrations of his first trans-Atlantic crossing, some facts cannot be disputed. There may be different opinions on the identity of the four unsettled islets he left uncharted as he passed through the Bahamas. But it was on Cuba that the first great encounter between Americans and Europeans took place that was to set world history on a new course. The arrival of Columbus's three caravels on Cuba in 1492 started a series of transoceanic contacts that were to weld two separate branches of mankind together and to change human lives throughout the world.

Christopher Columbus was the single individual who laid the plans and took the calculated risks that led to this historic event. Both blessings and disasters proved to be the outcome of his successful ocean crossings. Endless shiploads of American art objects in gold and silver, often melted down to be valued as metal weight, saved poverty-stricken nations in Europe, where millions of hungry families were fed with food plants never before seen east of the Atlantic. But westward, in the wake of the cross and the Scriptures, came also conquest and diseases that wiped out entire tribes and put an end to old and mighty nations.

No wonder then that the arrival of the first Europeans in America is viewed with mixed feelings throughout the world. But history must not blame the intrepid navigator Columbus for the crimes and horrors committed by people of all creeds and colors who followed in his wake. Individuals, tribes, and whole nations had fought each other on either side of the world oceans for untold ages before Columbus sailed the seas.

Historians and archaeologists throughout the world divide America's past into a pre-Columbian and a post-Columbian period. For those who look at the events in 1492 with a European perspective, American history begins with Columbus. What happened on the west side of the Atlantic earlier is prehistory, and by definition history begins with the European written record. The oral history of the pre-Columbian civilizations in America, even what some Native Americans wrote with their own script on stone stele and in folded paper books, was treated with suspicion and generally called myth and legend, not history. To the despair of modern scholars who attempt to reconstruct the American past, some of the first Christian clergy to reach the New World burned as many of the ancient paper codices as they could lay their hands on. To them the history of the pagan priest-kings was evil heresy that ignored the biblical genealogy andthe royal dynasties known in Europe. Our zero year for the early Americans begins when European history and Abraham's faith were imported across the Atlantic.

When we celebrate the anniversary of Columbus's arrival, let us bear in mind that this event began American history only for those who lived in Europe. For those who lived in Cuba at that time, it marked not the beginning, but the end. The Cuban population today is composed mostly of people of Old World origin. Let us not blame Columbus for all that happened, but let us celebrate the memory of those who were there to give him a friendly welcome.

No less authority than Columbus himself wrote the lines that could be on the common tombstone of Cuba's pre-Columbian inhabitants. On Christmas Day in 1492, with the memories of the Great Encounter still fresh in his mind, Columbus wrote to the sovereigns of Spain his own impression of the reception he experienced in Cuba: I assure Your Highnesses that I believe that in all the world there is no better people nor better country. They love their neighbors as themselves, and they have the sweetest talk in the world, and are gentle and always laughing. The same words of praise were repeated in his own Diario for both Christmas Eve and Christmas Day.

With these words, Columbus left the friendly and peaceful people of the New World behind in December 1492, a date that for us marks the end of the pre-Columbian period. Neither priests nor soldiers accompanied Columbus on this first voyage to America. And his praise of the people he encountered was repeated in the writings of his contemporaries with access to firsthand descriptions from Columbus and his companions.