Contents

Guide

Praise for How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog

Anthony McGowans wonderful survey of philosophy Hugely entertaining and accessible, there cant have been more delightful exponents of Socratic dialogue than McGowan and Monty, his scruffy and evidently delightful Maltese terrier.

Tom Holland, Best Books of the Year, New Statesman

For essential reading on both the meaning of dogs and the meaning of life, I can recommend Anthony McGowans wonderful book How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog, a series of conversations he had with his dog, Monty, while out walking together. The final chapter is a touching meditation on death and the existence or not of God, that takes in everything from Aristotle to Schopenhauer and leaves you suspecting dogs might already have had many of the answers all along. There are more things in heaven and earth, Horatio / Than are dreamed of in your philosophy.

Guardian

Filled with sparkling insights, a joy from start to finish. In turns witty, brilliant and irreverent, McGowan explains nothing less than the meaning of life to his dog. If only we were all as lucky as Monty to go for long walks with the author

Peter Frankopan, author of The Silk Roads

Genuinely profound as well as very funny.

Alex Preston

An accessible, amusing guide to key philosophical questions Perfect for novice philosophers.

Idler

Readable, funny but enlightening.

Church of England Newspaper

There is no sharper, funnier, cleverer writer in Britain today.

Robert Twigger, author of Micromastery

Anthony McGowans How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog is a delightful, quirky book that deserves a wide readership and may well get it A witty, enjoyable book that gently introduces some serious philosophy, with plenty of smiles along the way.

Nigel Warburton, Five Books

A charming, informative, unique introduction to Western philosophy.

Kirkus

McGowan playfully explores philosophy in this amusing collection of imaginary dialogues conducted with his Maltese terrier, Monty. Readers who have never roamed the paths of philosophy before, or who could use a return trip, will appreciate this enjoyable tour from a friendly guide and his loyal companion.

Publishers Weekly

To Gabriel, Rosie and, of course, Monty

Contents

Preamble

Reader, meet Monty, who is to play a role in this book: not perhaps the star, but definitely up for best supporting actor. Monty is a Maltese. I sometimes erroneously describe him as a Maltese terrier, which is straightforwardly incorrect. Although in some ways terrier-like in his tenacity and occasionally unfocused aggression, the Maltese is from a quite different family of dogs, and belongs on the lap, not down tunnels hunting for rats. Its always struck me as odd that Maltese are always referred to as Maltese dogs. This seems rather unnecessary: no one is going to mistake Monty for a Maltese rabbit, or Maltese guinea pig, although I suppose you might mistake him for a Maltese muff. Hes fluffy and white and when washed and blow-dried resembles a dandelion clock. At other times he can appear a bit scraggy and bedraggled, like a heavy sneeze come to life. And the tendency of Maltese to develop dark tear stains below their eyes, for all the world like run mascara, makes him look like an albino goth in the midst of an emotional crisis. Although Maltese are not renowned for their intellect, Monty has a quizzical, enquiring sort of look, and often cocks his little head to one side, which makes him at least appear to be a good listener.

So much for Montys appearance, but here were more interested in his character. I expect that you, if youre a dog owner, chat to your dog. Perhaps its mainly a matter of endearments and encouragement, interspersed with demands that they come or sit or stop chasing that postman. I also suspect that for some of you at least, your dog talks back. Perhaps he does it by the traditional canine mediums of barking, yowling, growling and tail-wagging. Perhaps it takes a more eloquent form, the words appearing in your mind, in a way that you can then articulate. Whats that? You want a biscuit? And you want it now?

Monty is an unusual dog in quite how well he manages to convey his thoughts. This was a skill he developed in a series of walks recorded in How to Teach Philosophy to Your Dog, which gave Monty a thorough grounding in the dialectical method, in other words, how to learn through conversation.

Now, one understands that there might be, in the mind of the reader, a small degree of scepticism (a subject, incidentally, dealt with at length in the aforementioned book) about the extent to which a mere pooch could engage in relatively sophisticated intellectual debate. In that case I will offer you an alternative. In The Third Policeman, the great Irish novelist and humorist Flann OBrien describes the process by which a man and a bicycle can, by means of the simple scientific truth of Brownian motion the jiggling about of molecules in any substance combined with the close contact of the fundament and the saddle, become so intertwined and enmeshed that no clear distinction between the one and the other can be drawn. This leads to the many instances of human-like behaviour in bicycles that tendency, for example, for bikes to nestle next to radiators in hallways during inclement weather. Something similar undoubtedly occurs with a dog and its owner. Those hours of stroking and lap-sitting (which is where Monty is right now, by the way, having his post-supper nap) have inevitably taken us to the point at which Monty is, to some unspecified degree, me, and me, Monty. So, in the walks that follow, you are at liberty to imagine either a McGowan-infused Monty, or a Monty-infused McGowan, as the junior partner in these discussions.

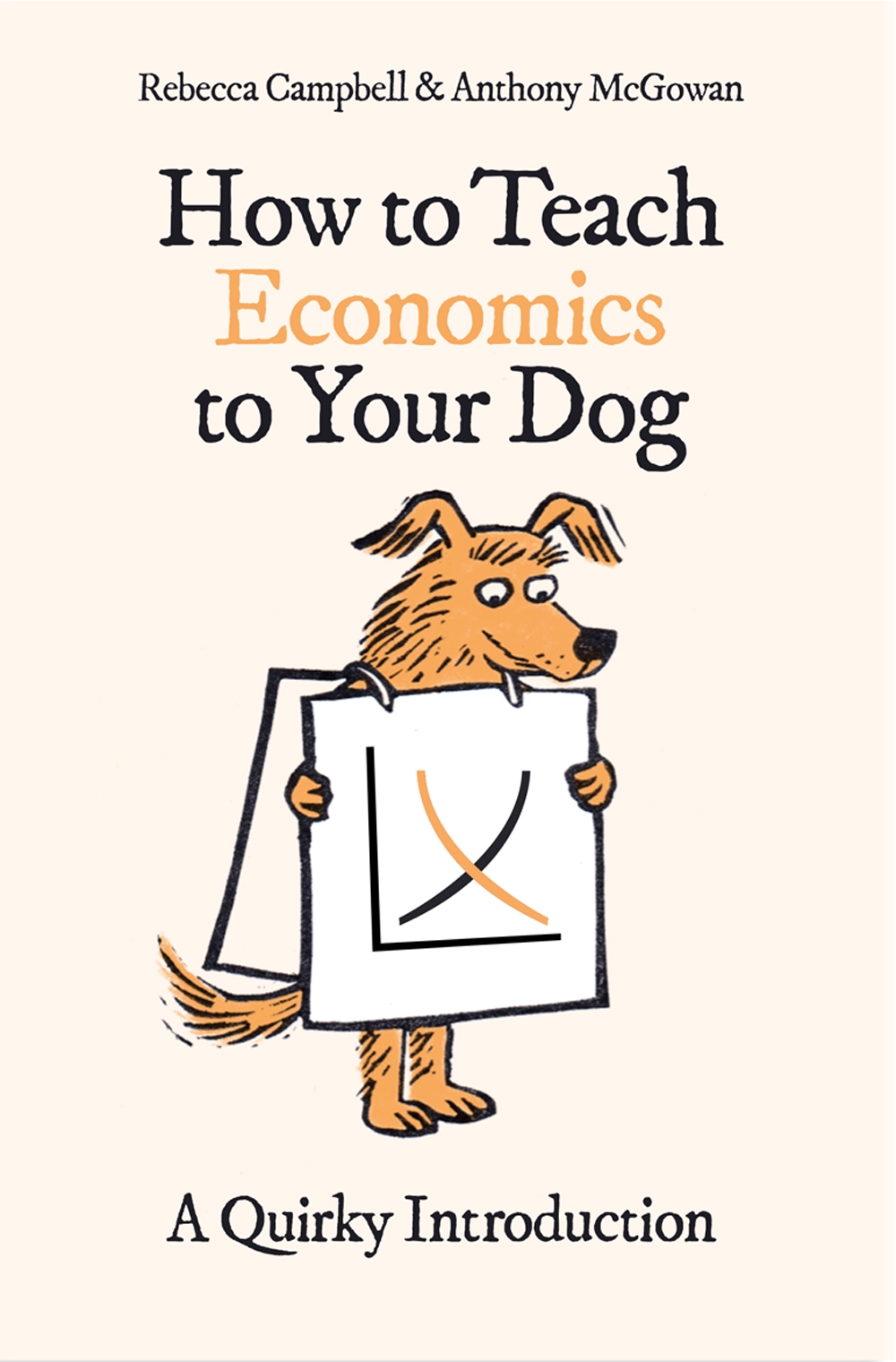

Following our philosophical perambulations, it was quite clear that Monty wanted more. Philosophy is many things: a way to polish the blunted tool of your rationality; an engaging series of stories about what may make up the nature of reality; a guide to living a more ethical life. However, it could be argued that philosophy leaves much of the reality of existence out of the picture, everything on the small scale about our daily struggle to earn a living, to, on the larger, the way in which societies should be organised to bring the maximum benefit to the greatest number of people. This is quite a big hole in the understanding of any person (canine or human). It is the job of economics to fill this gap, hence the title of Robert Heilbroners classic book on the history of economics, The Worldly Philosophers. It is economics that gives we philosophers a sharp kick in the pants, redirecting our attention from the clouds to ground level.

In our lives, we are enmeshed in complex economic forces, generated by the way things are made, traded, sold. These forces determine the kind of lives we are able to lead. Of course there is an underlying humanity connecting us all, but the infinitely complex texture of modern life, how we spend our working days, where we live, what we wear, what we eat, how finally we spend our retirement, is determined by these vast inhuman forces. Economics is the greatest tool we have (and, as a philosopher, this stings, it truly does) for understanding these forces.