BOOKS BY STEVE RAYMOND

Kamloops

Backcasts

The Year of the Angler

The Year of the Trout

Steelhead Country

Copyright 1994 by Steve Raymond

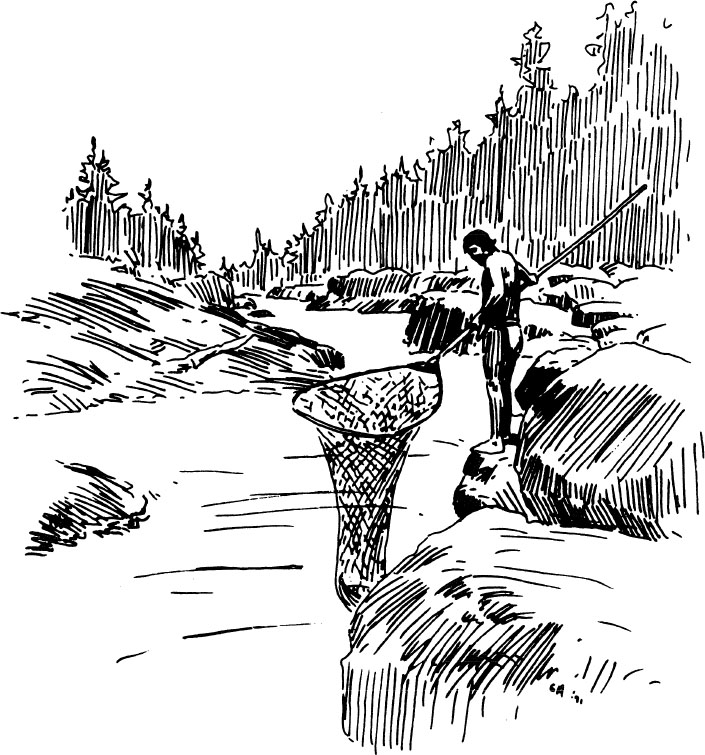

Illustrations copyright 1994 by Gordon Allen

Originally published as a hardcover edition in 1991 by Lyons & Burford, Publishers, New York, NY

First Skyhorse Publishing edition 2015

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any manner without the express written consent of the publisher, except in the case of brief excerpts in critical reviews or articles. All inquiries should be addressed to Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018.

Skyhorse Publishing books may be purchased in bulk at special discounts for sales promotion, corporate gifts, fund-raising, or educational purposes. Special editions can also be created to specifications. For details, contact the Special Sales Department, Skyhorse Publishing, 307 West 36th Street, 11th Floor, New York, NY 10018 or info@skyhorsepublishing.com.

Skyhorse and Skyhorse Publishing are registered trademarks of Skyhorse Publishing, Inc., a Delaware corporation.

Visit our website at www.skyhorsepublishing.com.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Raymond, Steve.

Steelhead country: angling for a fish of legend/Steve Raymond; illustrations by Gordon Allen. First Skyhorse Publishing edition.

pages cm

Originally published: New York: Lyons & Burford, 1991.

ISBN 978-1-63450-414-0 (pbk.: alk. paper) ISBN 978-1-5107-0143-4 (ebook) 1. Steelhead fishingNorthwest, Pacific. 2. Fly fishing Northwest, Pacific. I. Title.

SH687.7.R39 2015

799.1757dc23

2015026019

Cover design by Richard Rossiter

Cover photo: Thinkstock

Printed in the United States of America

F OR

Enos Bradner and Ralph Wahl

C ONTENTS

P ROLOGUE

T HE NORTHWESTERN tip of North America leans over the Pacific Ocean like an old cedar limb weighted down with rain. The limb has a long reach and casts a long shadow that falls all the way down to the northern California coast. Out of that shadow ten thousand rivers run.

In these rivers the steelhead trout evolved.

Probably the steelhead could have come from nowhere else but this misty, dark corner of the world. It is a realm of vast landscapes, of cold mountain rivers flowing down through silent, shadowed forests, of relentless gray skies and unremitting rain, of ragged coastlines honeycombed with hidden harbors and secret bays where bright rivers mingle with the sea.

Certainly the steelhead is well matched to this environment in all respectsin its color, in its shape and strength, even in its temperament. It can be as dour as the misty weather one day and as bold as bright sunshine on the next. It fits into the rivers smoothly and easily, blending with the camouflage of their rubbled bottoms or disappearing into the deep shade from fir and cedar limbs along their banks. It is elusive and mysterious, but also strong and spirited enough to force its way upstream against the momentum and force of the vast weight of water ever spilling down from the foothills and the snowy peaks beyond them.

The steelhead is born in the quick and lively waters of these mountain rivers and it spends its early life feeding and growing in their shallow shaded runs until it feels the first tugs of the migratory instinct coded deeply in its genes. Then it rides the spring torrents down to the ocean and makes its way along fog-shrouded passages winding through a labyrinth of offshore islands until at last it finds itself alone beneath the broad Pacific swells. Following strong currents that flow like invisible rivers through the sea, it sets forth on a great feeding migration far to the north and west where it mingles in the trackless ocean with thousands of others of its kind, born of hundreds of other rivers.

For months or even years the steelhead continues on this journey, growing ever larger and stronger as it forages in the rich dark pastures of the ocean until finally, deep inside, it feels the seeds of its offspring take root and begin to grow. And then, in response to some exquisite mechanism of natural timing, it obeys an instinctive urge to turn toward home.

Back it comes, swimming now against the invisible currents that have borne it so far, pressing onward until the clouded coast is once again within its reach. As it enters the sheltered coastal waters it somehow perceives the scent of its home river, unique from all others, and follows that scent back to the estuary it left so many months before. There it waits restlessly for a rising tide to boost it back into the familiar current where it first knew life.

Only a few come back of all the silvery host that left the river years before, only the few that were quick and strong enough to survive all the predators and perils of the long journey. But those few have grown into mighty fish, fat and strong with the stored-up energy of the ocean, streamlined in shape to breast the forceful current, bright as the gleam of sunlight reflected from a wave.

Little wonder it is, then, that anglers wait anxiously for the steelheads return. This they have always done, from the days when Indians fished only for food and sport was an unknown concept, and this they still do in greater numbers than ever before. Now the riverbanks are lined with long ranks of weekend anglers, a fresh gantlet of rods waits at every turn of the river, and each returning steelhead faces a new test at every foot of its upstream journey.

The fishermen wait and scheme and fuss with a great singleness of purpose for a chance to grapple with one of the few returning fish. They know, either from hearsay or experience, that hooking a steelhead is a little like hooking a lightning bolt, that the fight of their lives awaits them, and they look forward to it with a degree of anticipation and perseverance that is impossible for a nonfisherman to understand.

But for the steelhead there is a heartbreaking finality to these struggles for life, so close to completion of its long journeyunless, as now happens more and more frequently, the victorious angler is willing to settle for the memory rather than the fish itself, and the exhausted steelhead is returned to the river to rest, recover, and continue on its way.

The return of the steelhead is an integral part of life in the great Pacific Northwest. A whole tradition has grown up around it, a tradition with a complicated code of behavior and ethics, a complex set of tactics, and a growing body of literature and lore to which each succeeding generation of anglers contributes its own share. The steelhead has become a fish of legend in tales told around the campfires that flicker on countless riverbanks in the raining dawn, or in tall stories swapped over steaming cups of coffee in the greasy-spoon diners of little towns clustered along the rivers. There are other great fishing traditions, but none quite the same as this. Perhaps one must be born in the Pacific Northwest, or at least spend much of his life here, to fully understand and become a part of it.

Next page