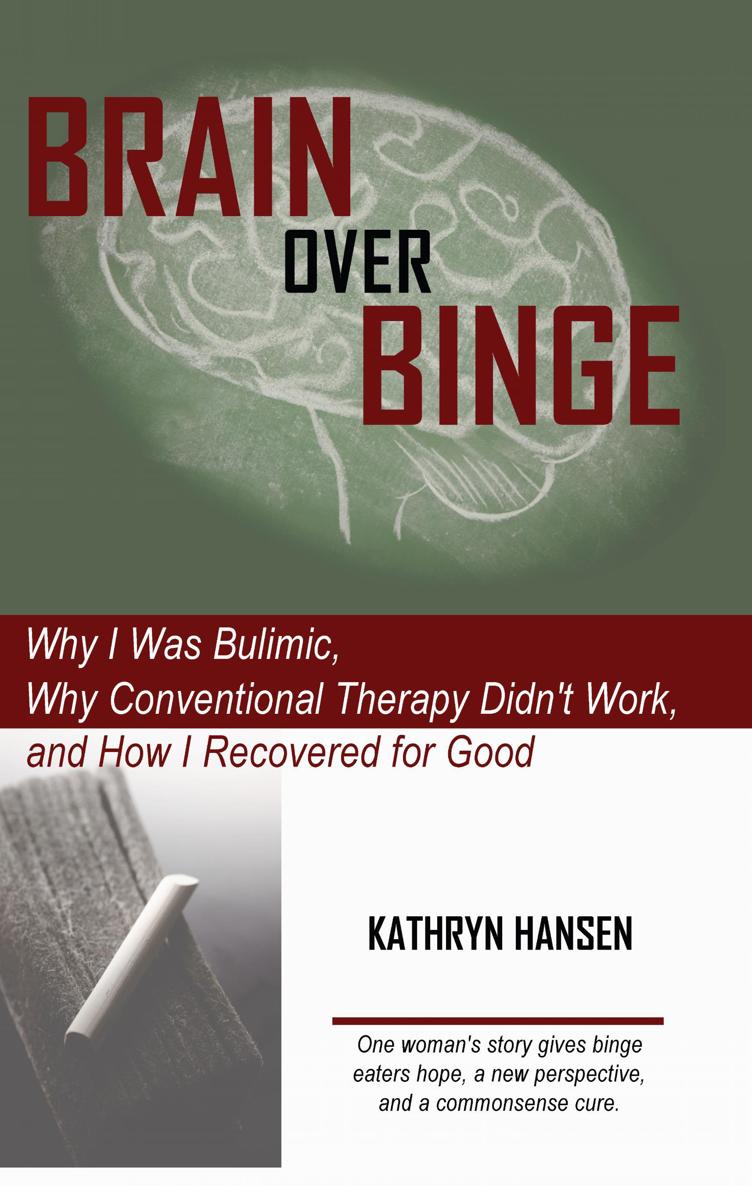

BRAIN OVER BINGE

Why I Was Bulimic, Why Conventional Therapy Didn't Work, and How I Recovered for Good

Kathryn Hansen

Copyright 2011 by Kathryn Hansen

Camellia Publishing

6825 S. 7th St.

Box 8305

Phoenix, AZ 85066

www.camelliapublishing.com

Printed in the United States of America

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the written prior permission of the publisher.

ISBN: 978-0-9844817-2-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010911736

NOTICE OF LIABILITY: This is a personal story of recovery. It is not intended to replace the services of trained health professionals or be a substitute for medical advice. You are advised to consult with your health care professional with regard to matters relating to your health and, in particular, regarding matters that may require diagnosis or medical attention. The author and publisher disclaim any liability arising directly or indirectly from the use of this book.

This book is for the 19-year-old bulimic who felt hopeless yet swore to conquer her problem one day and then write about it.

That bulimic was me ten years ago....

So now I dedicate Brain over Binge to my former self and to all those who want to be free of binge eating.

Contents

Preface

"[A]n eating disorder provides solutions to one's problems in life and is not simply about food and weight."

I n November 2007, two and a half years after I recovered from bulimia, I visited my doctor about some stomach pain. I told him about my past eating disorder, because I thought years of binge eating could have caused some damage to my digestive system. Even though I made it very clear that I had not binged in a long time and was no longer bulimic, he asked me, "Do you think your eating disorder is" He hesitated, so I finished the sentence for him: "Gone?" Then I answered my own question with a simple "yes."

"That's great," he said. "So I assume you sought help?"

"Yes, I did go to therapy, but then I realized it was just a habit and I quit."

A look of interest, or perhaps doubt, came across his face. "Well," he said, "I'm sure your bulimia was fulfilling some need."

Fulfilling some need ... the words struck me, and suddenly, I felt as if I were sitting in a therapist's office again.

I was attempting to write this book at the time but wasn't making much progress. I found new motivation that day. My doctor's comment made me realize that there is a big problem with the way bulimia is viewed, not just among therapists and patients, but throughout society.

Today, eating disorders are primarily thought to be symptoms of psychological problems like depression, anxiety, low self-esteem, and family conflicts. Eating disorder experts assert that the destructive eating behavior signals an inner emotional crisis, just as fever indicates an underlying infection. An affected individual supposedly uses the eating disorder as a coping mechanism to deal with issues and feelings she can't face in her life. In this way, eating disorders are thought to fill an important need or void in the person's lifea need that is much more than physical, which is why it's so common to hear that eating disorders are not about food.

I believe that the widespread view of bulimia as a complicated problem that helps victims fill some sort of emotional need is a shaky hypothesis at best; and in practice, it can be downright harmful to people suffering daily with incessant urges to binge and purge.

A bulimic typically seeks therapy because she can't seem to stop eating large quantities of food. But in therapy, she learns that food really isn't the problemthe problem is her personality, her inability to cope with life, her childhood, and/or her relationships. In short, she learns that she is psychologically unwell. No one tells her exactly how to stop the behavior she so desperately wants to stop. There are no specific directions, no pinpoint cure. No one tells her that she has the power to stop binge eating anytime she chooses. Instead, she learns she doesn't have much control over her own behaviorthat is, until she addresses the underlying emotional issues.

So the bulimic sets out on a path of self-discovery, hoping to find some answers to why she binges, hoping that if she makes some changes in her life, heals past hurts, or builds new relationships, the incredible urges to binge and purge will go away. She learns to deal with depression, reduce anxiety, and build healthy self-esteem. She works on her nutrition, battles her perfectionism, and learns to cope with the events and feelings that supposedly trigger her binge eating episodes. She tries to figure out what purpose the bulimia serves in her life. But all the while, she continues to binge and purge.

This was my story for six years. After an initial reluctance, I embraced therapy. I embraced the view that my bulimia was about something more than food; I embraced the idea that I was using my eating disorder to cope; I embraced the idea that I was ill, that I needed professional help to get well, that I needed to get to the root of my problem before I could quit. I did everything I was supposed to do in therapy, and when it didn't work, I tried different therapists, slightly different approaches. But all this had the same result: I remained bulimic.

I don't blame my therapists because, after all, they were only trying to help me and they were always sensitive and supportive. Therapy simply didn't empower me to stop binge eating, and there are many like me who have had the same experience. Although there is a wide range of recovery rates in the available literature, current therapies for binge eaters do not come close to curing everyone. There is no consensus on exact recovery rates because of problems in research, including a limited number of studies, study design flaws, differing definitions of eating disorders and recovery, different treatment types, and patient withdrawal from studies.

One study showed that, after treatment, 50 percent of bulimics maintained bulimic behavior with episodic remissions and 20 percent remained symptomatic.

These statistics show that although therapy does help some bulimics, it does not help them all. Therefore, alternatives are needed. After talking to my doctor that November day, I felt a strong desire to provide an alternative. I realized the view of bulimia as a coping mechanism is so pervasive in our society that it is generally accepted as fact, even by those outside of the therapy community, like my medical doctor. I decided that a new voice was urgently neededa voice to challenge this orthodoxy and reach those who are not being helped by this view of bulimia. I also want to give hope to those who are not currently seeking therapy, because about nine out of ten people do not receive treatment for their eating disorder.

Fulfilling some need ... I thought about those words over and over, trying to understand why my doctor's simple and innocent comment kept lingering in my mind. I reflected on my experience in therapy and how the experts led me to believe that by binge eating, I was using food to cope with my problems, stuff down emotions, or fulfill a more complex psychological need.

Then I thought about the way I changed once I'd decided to view my eating disorder differently: by dismissing the belief that I ate for deeper, more profound reasons and, in turn, completely changing how I approached my problem. I'd discovered another path to recovery, a simple and quick way to stop my bulimiawithout therapy. I have completely stopped bingeing, and I have had no desire to do so in years. I believe that I am at zero risk for relapse, even during stressful times in my life. My bulimia is over.

Next page