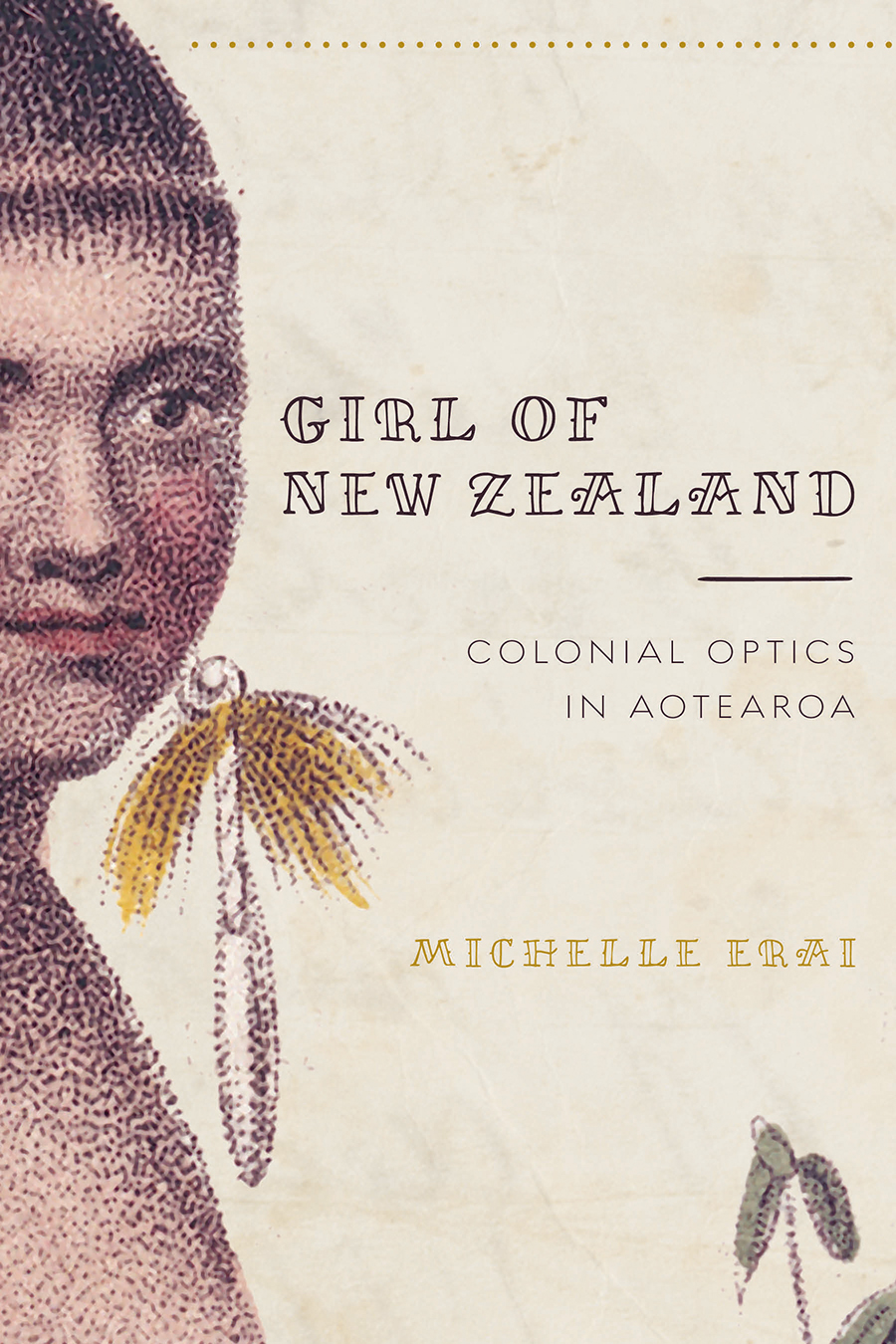

Girl of New Zealand

Critical Issues in Indigenous Studies

Jeffrey P. Shepherd and Myla Vicenti Carpio

SERIES EDITORS

ADVISORY BOARD

Hklani Aikau

Jennifer Nez Denetdale

Eva Marie Garroutte

John Maynard

Alejandra Navarro-Smith

Gladys Tzul Tzul

Keith Camacho

Margaret Elizabeth Kovach

Vicente Diaz

Girl of New Zealand

COLONIAL OPTICS IN AOTEAROA

Michelle Erai

The University of Arizona Press

www.uapress.arizona.edu

2020 by The Arizona Board of Regents

All rights reserved. Published 2020

ISBN-13: 978-0-8165-3702-0 (paper)

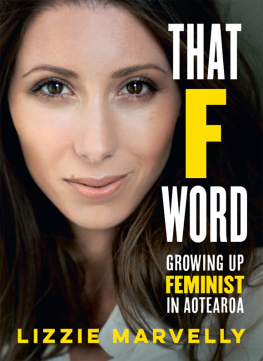

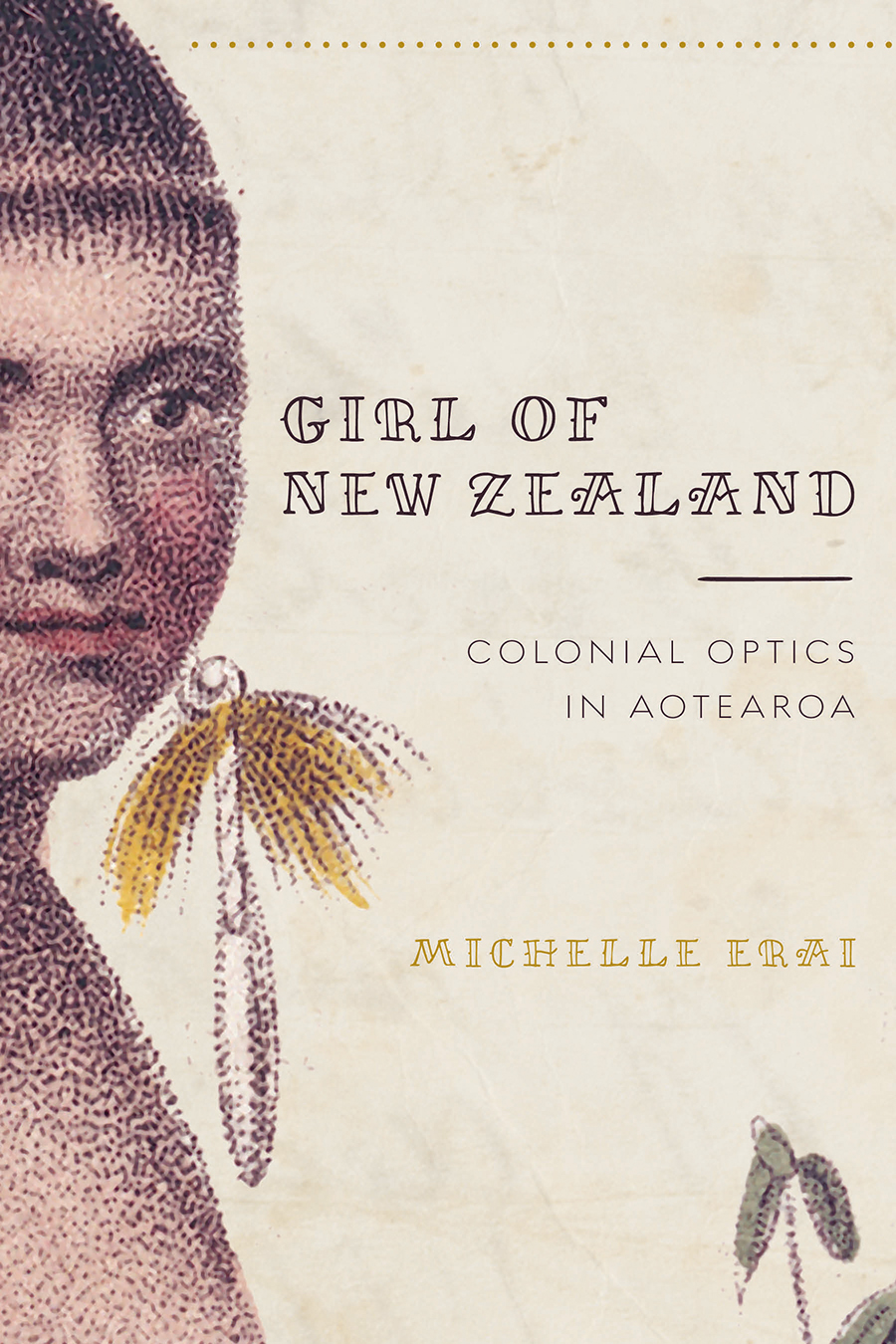

Cover design by Leigh McDonald

Cover art: Piron, Jean, Girl of New Zealand, 1793. Courtesy of Alexander Turnbull Library, Wellington, New Zealand, Reference No. PUBL-0172-2-13.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Erai, Michelle, author.

Title: Girl of New Zealand : Colonial Optics in Aotearoa / Michelle Erai.

Other titles: Critical issues in indigenous studies.

Description: Tucson : The University of Arizona Press, 2020. | Series: Critical issues in indigenous studies | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019046620 | ISBN 9780816537020 (paperback)

Subjects: LCSH: Women, MaoriSocial conditions. | Women, MaoriViolence against. | Maori (New Zealand people)History. | Maori (New Zealand people) in art.

Classification: LCC DU423.W65 E73 2020 | DDC 305.48/899442dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019046620

Printed in the United States of America

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

Contents

Illustrations

Prologue

O ne evening driving home from San Francisco I was listening to an interview with author Toni Morrison on the radio, and when asked about the ghost narratives in her writing she said she wanted to make history get up out of the grave and sit at the kitchen table. I want these images to climb down from the archives and onto your desk. It is no accident that I align this book within a heritage of fictionit belongs there as much as on the shelves of history, feminism, visual culture, and postcolonial theory. The analyses here come from those intellectual lineages, but there are many genealogies at work; so much of what I suggest is conjecture, and the gaps between certainties far too wide for one person or theory to bridge. Ultimately, I hope that you will look at these images and see things I did not and that you will imagine other ways to denaturalize the uneven operations of power through violence and its sometimes benign-seeming optic representations.

Acknowledgments

F irst, Id like to acknowledge my tribes, Ngpuhi and Ngti Porou, and the tribes of North America on whose land I wrote and worked, particularly the Tongva and Ohlone. While I was a graduate student I was lucky to be part of an amazing cohort of students in the History of Consciousness program at the University of California, Santa Cruz; the Womens Studies (now Feminist Studies) Department was also incredibly generous and supportive. I was fortunate to receive funding for early research from the UC Pacific Rim Group (no longer in existence). I found intellectual homes in the Native American and Indigenous Studies Association, the UC Office of the President, American Indian Studies Center and Gender Studies at UC Los Angeles, and Ng Pae o te Mramatanga, Aotearoa. The Faculty in Residence Program at UCLA provided me with a physical home and greater access to a broad range of students, as did my associations with the Center for the Study of Women, Faculty Support Program, Amerasia Journal, and the Fowler Museum at UCLA. The University of Arizona Press has shown great patience and support in the production of this book, for which Im especially appreciative. In Aotearoa it was a privilege to take a break from academia and work with Amokura, a consortium of the seven northernmost tribes brought together to try to end violence within Mori families. Their analyses have since guided much of my life and work. During my archival searches, I was helped immensely by staff at Victoria University, Alexander Turnbull Library, the National Library of New Zealand, Victoria State Library (Australia), the School of Oriental and African Studies at the University of London, the British Library, and the archives held in Birmingham University.

There are many people I need to thank personallyIm so sorry for names left outif youve housed, fed, or hugged me during this process Im thinking of you. In particular, Im grateful to my family, Leone, Roy, Steven, Kath, Sean, Olivia, Annette, John, Chrissy, Sarah, George, Juneen, and Logan. My rainbow whanau, Andy, Cathie, Ruth, Karyn, Jody, Rose, Jo, Janine, Fiona, Tharron, Jack, Dot, Gay, and Gwenn. My Uncle Jax and his friends were my measure for hard work (and kindness) at the Waipoua Forest Caf and Campgrounds, and Te Mauri Maori Cancer Support group at Kkiri Marae picked me up and carried me over the finish line.

To my teacher, Angela Davis, my eternal gratitude; other teachers have included Bettina Aptheker, Jim Clifford, Rosa Linda Fregoso, Herman Gray, Andrea Smith, Tracey Tawhiao, Keith Camacho, Juliann Anesi, Aurora Chang, Mishuana Goeman, Elizabeth Marchant, Piya Chatterjee, Di Grennell, Witi Ashby, Liz Deloughry, Jessica Cattalino, Rosamonde Miller, Lina Chhun, Allison Matheis, Lori Vogelgesang, Andrea Eve Hopkins, Kirsty Strong, and Alicia Cox. In Aotearoa three incredible women provided feedback on an early draftthank you, Alice Te Punga Somerville, Leonie Pihama, and Hinurewa te Hau. Im grateful to every student Ive worked with, and to four people without whom this book could never have happenedJenna, Van, Richard, and Samantha.

He mihi aroha ki a koutou katoa.

My gratitude and love to all of you.

Girl of New Zealand

Introduction

Colonial Optics

A nyone who has spent a good amount of time on the ocean will have seen low-lying land on the horizon, with cloud masses mirroring above. Aotearoa, the Mori name for the small group of islands known as New Zealand, translates into Land of the Long White Cloud. The effect of imagining this perspective fixes the viewer as already a voyager, who, from a seat on an airplane or the boards of a canoe or ship, might discern, beneath those clouds, a land of possibilities.

In reading the description of the phenomenon of the clouds, you are being asked to build a picture in your mind, either from recalling a memory or by using your imagination. This process of employing a practice of optics is what this book is about. In particular, the book will propose three arguments: first, that the space between the mode of apprehensionin this case, the retinaand an object is not empty, it is filled with political ideologies; second, that consuming images can change a person; and finally, that the optic-izing process itself can be a violence. Based on a selection of images of Mori women, I explore how it is necessary to refuse the idea of an innocent eye in order to fully recognize how optics have been employed in the colonization of Aotearoa and conclude that art is a critical antidote to the damage committed through colonial ideologies.

In this introduction I outline some of the many theories and approaches I have drawn from to make sense of specific images reproduced within these pages. Some of these frames of reference are academic; others are processes that have emerged from growing up in Aotearoa and being taught to read and understand my environment in a broad, culturally expansive sense.

Next page