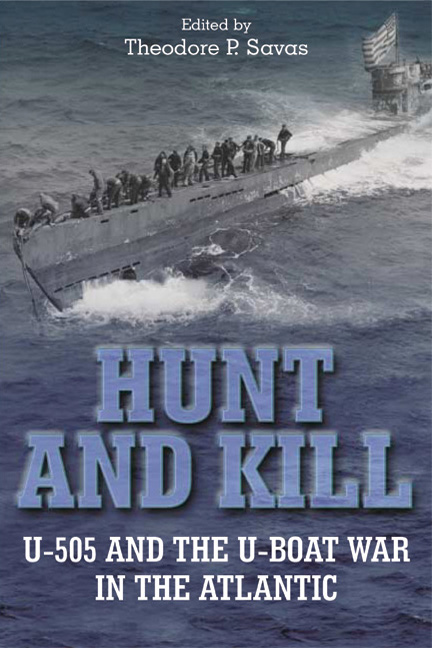

U-505s remarkable history, including its astonishing transformation from frontline U-boat to Chicago landmark, is only cursorily understood by most readerseven those with a deep interest in World War II naval history. This incomplete appreciation is understandable because most published accounts highlight only narrow slices of the boats complex three-year wartime history

Theodore P. Savas

Editors Preface

In the mid-1990s I organized and had the pleasure of serving as editor of a collection of essays written by leading U-boat scholars and published under the title Silent Hunters: German U-boat Commanders of World War II (Campbell, CA: Savas, 1997; Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2003). The criteria set forth for the selection of the biographical portraits were simple: choose a U-boat commander who has not received the scholarly treatment he deserves, one who either accomplished his record incrementally over several patrols or someone whose experiences were somehow unique and worthy of study. The result was a well-received compilation. Hopefully, others think it added something significant to the genres literature. At that time I believed other aspects of the U-boat war needed similar treatment, but my transformation from active lawyer to the publishing world, coupled with two cross-country moves in two years, delayed the book you now hold in your hands.

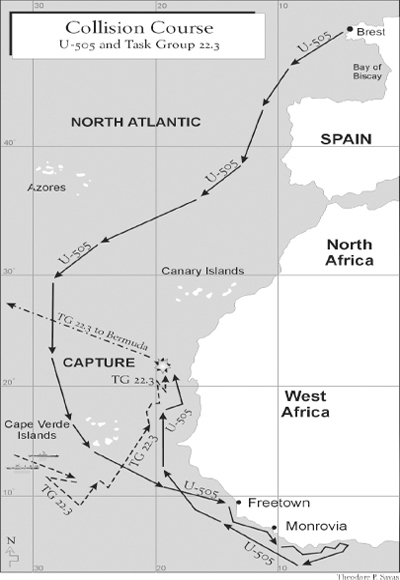

U-505 s remarkable history, including its astonishing transformation from frontline U-boat to Chicago landmark, is only cursorily understood by most readerseven those with a deep interest in World War II naval history. This incomplete appreciation is understandable because most published accounts highlight only narrow slices of the boats complex three-year wartime history: Axel-Olaf Loewes appendicitis while on patrol, Peter Zschechs gunshot-to-the-head suicide in the control room, and Harald Langes fateful June 4, 1944, encounter with the audacious Daniel V. Gallery and his Task Group 22.3. The boats postwar fate is similarly planed smooth, usually with little more than a sentence or two explaining that U-505 was transported to Illinois and can be toured at Chicagos Museum of Science and Industry.

The historical record of U-505 and its crew is much more interesting than these paltry few points and, until now, has never been fully told. After a long and thought-provoking tour of the boat in the late 1990s, I decided it was time to reassemble the team members and challenge them to tell it. The individual chapters they have prepared provide what we all hope is a broad and deep portrait of the history of U-505, its crew, the naval intelligence behind its discovery and seizure in 1944, and its final journey to Chicago and significance to future generations as a historical artifact and war memorial. Captain Gallerys capture of the boat off the African coast has been told and retold from his perspective, and so a conscious decision was made to weave the various threads of that event within several different chapters, which also made it easier to avoid having to present readers with what would otherwise have been an irksome overlap of coverage.

I remember clearly the first time I met Erich Topp. He was visiting family in Texas and was on his way to southern California before returning to Germany. Baylor Universitys Eric Rust provided me with his phone number. At Topps invitation I flew down to the desert on January 27, 1996. He walked outside to greet me and flashed a broad smile. He was 82 years old but looked 55tall, erect and handsome, with piercing ice-blue eyes, a firm handshake, and a hearty laugh. We struck it off immediately and I ended up staying many hours longer than originally planned. The honesty and forthrightness of his responses impressed me. Admiral Topp contributed to Silent Hunters with a moving essay about his deep friendship with fellow ace Engelbert Endrass, written while on patrol in the North Atlantic. Topp believed a book on U-505 was long overdue and kindly agreed to pen the Foreword for it. I have enjoyed our friendship over the years, and wish him continued good health.

Type IX U-boats played a unique role in the war. Their bulky size and slow diving capabilities rendered them less suited for convoy work than the more agile Type VII, though this was only fully realized after many good crews met their end raking North Atlantic lanes in search of clustered prey. The same girth and weight that made Type IXs clumsy convoy participants, however, furnished them with their potency as solo warriors. Their extra tanks held substantially more fuel, allowing them to operate as lone hunters for long periods of time in distant waters. First engineered in the mid-1930s, the Type IX series evolved over the years to become one of the most effective submarines in history. All of this and much more is carefully presented in our opening contribution, No Target Too Far: The Genesis, Concept, and Operations of Type IX U-Boats in World War II, by Eric C. Rust of Baylor University. Dr. Rust meticulously explains the evolution of the German navy and naval doctrine from the First World War through the tumultuous years preceding World War II, the development and technical aspects of this U-boat series, how the Type IX was employed during the war, and its place in German naval history. He also willingly compiled the technical data related to Type IXC boats that appears as Appendix A. As he did so ably with Silent Hunters, Eric graciously agreed to review and help edit each of the essays that appear in this book as well as pen its insightful Introduction. Erics keen observations, always graciously delivered, made this study stronger and more cohesive than it otherwise would have been. Over the years our friendship has grown, and for that I am both thankful and fortunate.