AUTHOR'S NOTE

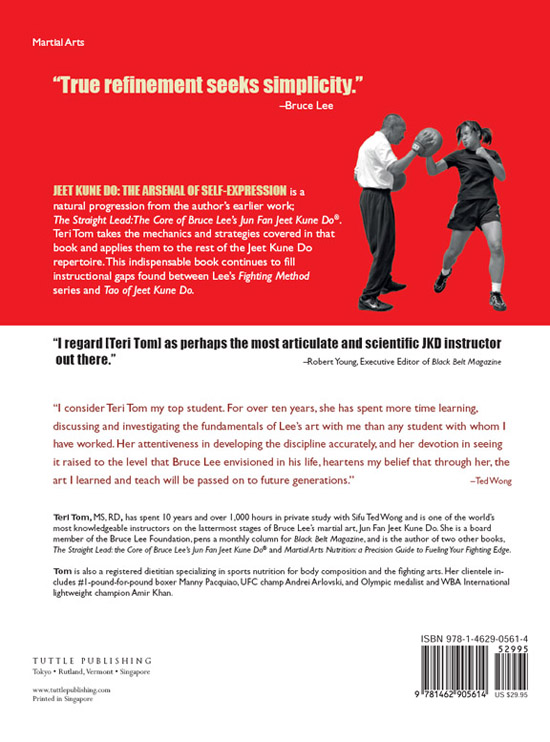

A s you may already know, the volume that you now hold in your hands was preceded several years ago by a little book called The Straight Lead: The Core of Bruce Lee's Jun Fan Jeet Kune Do. Through the study of a single technique, I traced the evolution of Bruce Lee's martial arts development out of Western boxing and fencing. I thought it important to come right out of the gate with an argument for the technique that is really the cornerstone of Jeet Kune Do, or more precisely in Bruce Lee's own words, "the core of Jeet Kune Do." All other aspects of the artother punches, evasive techniques, even the stancewere selected and developed around delivery of the straight lead.

While we briefly cover the lead punch in this book, we don't have enough room here to go into its history and origins. Nor do we have the space to cover some of the finer details of the mechanics. For a full understanding of the art, then, I recommend your reading this book's predecessor, as the material you are about to read is a natural progression from The Straight Lead. I've taken some of the basic mechanics and strategies covered in that book and applied them to the rest of the JKD arsenal.

The purpose of both volumes is to fill in some of the instructional gaps between the Fighting Method series and the Tao of Jeet Kune Do. As we noted in the last book, Bruce Lee did not intend for the Tao to be published as an instruction manual. It is merely a collection of his personal notes, most of which were taken from other sources. It is not a how-to booknor is the Fighting Method series. Unfortunately, Bruce Lee was never able to assemble what became the Fighting Method series as an instructional manual, and much of the material had become outdated by the time of his death. The photos that would comprise the Fighting Method books were taken early in the development of JKD in 1967. If you compare them to movie stills from Game of Death in 1972 and Enter the Dragon in 1973, you'll see that he'd made some very important modifications in the interim.

This is where we are so fortunate to have Ted Wong's powers of observation and analysis. As I've mentioned elsewhere, Ted Wong spent more time in private instruction with Bruce Lee than any of Lee's other students. Unlike many who claim to know Bruce Lee's art, Wong may be the only one truly qualified to make that claim. He was there. This is on record in Bruce Lee's own Day-Timer notes. Even more important than the frequency of sessions, though, is the time of those sessions. Wong had the fortune to study privately with Bruce Lee more than anyone else, but he also did so during the last stages of JKD development, right up until Lee's death in 1973. He is the most frequent, if not the onlyand this is documented as such in Lee's own handwritingwitness to JKD in its most advanced stages. Without his tireless study, Bruce Lee's life's work would be lost forever.

What you will find in the following pages are a lot of the small details that Ted Wong had observed during his time with Bruce Lee and his own discoveries as to how and why they work. You might think of this book as providing the information that connects the dots found in the Tao. Those small, nuanced movementslike footwork, feinting, weight transfer, and the sequencing of those elementsand how they're used to transition from movement to movement make all the difference. But they are not discussed in the Fighting Method series, which for the most part, just catalogs the techniques of JKD. Nor are they illustrated in the Tao. This book should be considered a supplement to both.

I've argued many times that Bruce Lee was and still is light years ahead of his time. In most sports, it's now a given that coaches incorporate principles of biomechanics into their training. For some reason, this shift has not occurred to the same degree in the martial arts. Lee, however, was already looking into biomechanics in the 1960's, when it was still unconventional to do so. As you'll see, there are passages in the Tao taken directly from one of the first kinesiology textbooks, which was written by Philip J. Rasch and R.K. Burke. You'll find that all the techniques in the JKD arsenal are in accordance with the principles of biomechanics and kinesiology and still hold true and are taught today. Because this is such an important part of JKD, I've dedicated a chapter solely to general biomechanics. As we go through each technique, you will want to refer to this chapter for further insight on the how's and why's behind them.

Finally, there has been so much malicious misrepresentation of Bruce Lee's art over the last three decades, I've cross-referenced, as I did in my last book, the original sources of Bruce Lee's writings. In accordance with the saying "talent borrows, genius steals," almost all of the technical notes that comprise the Tao of Jeet Kune Do and Commentaries on the Martial Way are passages that come from other sources. You will see that there are no references to wing chun, kali, or escrima. There is also very little coverage of grappling techniques. This is why there are only nine pages of grappling techniques in the Tao. The majority of that book, as is the case with Bruce Lee's personal notes, is almost exclusively comprised of passages on boxing technique and fencing strategy. Having actually been through Bruce Lee's handwritten notebooks, I can say that, with the exception of the sections on Zen philosophy, virtually everything is Western in origin. Most of the fencing notes come from Aldo Nadi, Julio Martinez Castello, and Roger Crosnier. There are also boxing influences from a wide range of sources including Jack Dempsy, Jim Driscoll, Thomas Inch, Edwin Haislet, Peter McInnes, and Bobby Neill.

The passages in those volumes of personal notes make up the majority of the Tao and are also found in Commentaries on the Martial Way. These notes are from the most advanced stages of JKD development. There are those who claim all sorts of origins of JKDfrom Filipino martial arts to wing chun. They will want to argue this point endlessly. I suggest they first take the cross-references here, track down the original sources and see for themselves, clear as daylight, that Jeet Kune Do is Western in origin.

CHAPTER ONE

BIOMECHANICS 101

T his isn't a biomechanics textbook, and it's beyond the scope of this volume to go into the finer details of that science, but an understanding of some basic principles will give you a much better understanding of Jeet Kune Do. On so many fronts, Bruce Lee was light years ahead of his time, and this arena is no exception. Breaking down professional sports to a science may be commonplace these days, but in Lee's time, that kind of analysis was only just beginning. While he may have surveyed many other arts, what he chose to incorporate into his own repertoire was very specific and considered, resulting in an art essentially limited to 4 or 5 punches, 3 or 4 kicks, and a few grappling techniques.

We'll touch on some of the strategic elements later on, but first, we must learn to perform them correctly. And what will help you refine these techniques to perfection is a basic understanding of why Bruce Lee chose to do things a certain way. A lot of people neglect this aspect of the art and move on to application. But failing to build a strong technical foundation is like trying to drive without learning how to put the key in the ignition. It makes no sense, and you'll end up going nowhere. Sloppy technique makes for sloppy application.