Copyright 1987 by Annette Tapert

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by Times Books, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

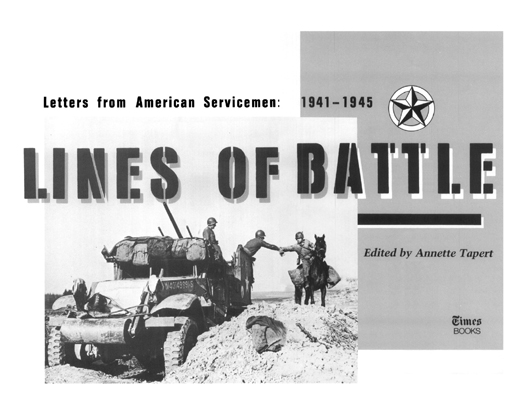

All photographs are reprinted by kind permission of the picture libraries of the National Archives and the Library of Congress or have been generously loaned by the letter writers or their heirs, with the exception of the photographs of John F. Kennedy (provided by the John F. Kennedy Memorial Library) and Russell Lloyd (provided by the Marine Corps Museum). The photograph of the letter written by Andrew Sivi on Hitlers personal stationery was loaned by Colonel Larry J. Michael. The cartoons on are reprinted by permission of Bill Mauldin and WIL-JO Associates, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Lines of battle.

Bibliography: p.

1. World War, 19391945Personal narratives, American. I. Tapert, Annette.

D811.A2L53 1987 940.548173 86-14478

eISBN: 978-0-307-81877-5

is an extension of this copyright page.

v3.1

Contents

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Most of the letters that appear in this anthology have never been published before. Some were acquired through personal solicitation, but the majority came to me in response to public appeals in regional newspapers, magazines, and military journals. I am indebted to the many publications that publicized my request for war letters. Although it was impossible for me to include all of the letters I received, I wish to thank everyone who took the time and interest to respond to my appeal.

A few of the letters I have included were selected from the outstanding collections at the Military History Institute at Carlisle Barracks in Carlisle, Pennsylvania. I want to thank Dr. Richard Sommers, Chief Archivist-Historian, and his conscientious and courteous staff for all their assistance. I am also grateful to Michael Miller, Curator of Personal Papers at the Marine Corps History Museum, and Terry Anderson at the Witness to the Holocaust Project, Emory University.

On a more personal note, I want to thank my parents, who dealt with the mountain of correspondence that arrived on their doorstep almost every day for nearly a year. And a special thank you to Jesse Kornbluth; his support and invaluable help went above and beyond the call of duty.

The last and most important acknowledgment goes to my contributorsthe true authors of this book.

FOREWORD

BY

David Eisenhower

As the years go by, the events recounted in Lines of Battle recede in time, but World War II remains a subject of intense interest. The fortieth anniversaries of D-Day, V-E Day, and other events have come and gone, but others approach, beginning next year with the fiftieth anniversary of Munich. Though Munich will not be celebrated, other events will be, particularly by the American people who look back on World War II as a supreme national achievement. For Americans and millions more, the war remains a living memory, a fact borne out by the recent controversies over President Reagans visit to the military cemetery at Bitburg, West Germany, and Kurt Waldheims election as president of Austria. Equally dramatic proof of this was the selection of Elie Wiesel as the recipient of the 1986 Nobel Peace Prize, an award tendered not for his involvement in any current crisis but in recognition of Wiesels thirty-year effort to keep alive the memory of the Holocaust. These episodes reaffirm the universal feeling that the world dare not forget World War II.

And so the memories live on, for reasons that are self-evident. The scale of World War II was unprecedented. So was its savagery, which stands as a timeless warning about the illusions of progress. The political, military, social, and economic ramifications of the war are still deeply felt. In short, for the foreseeable future, the war looms as a unique event and its outcome remains the foundation of world politics, albeit an eroding foundation. For as time goes on, as William Jovanovich put it, the past is always compromised by the present; many of the assurances of long ago, on reexamination, turn into questions and speculations. And as the speculations grow, it is crucial to recall the assurances accepted by the participants of the war, lest the past be forgotten altogether.

Thus, Lines of Battle is more than a selection of letters about a bygone period of special interest to the families of the recipients and of passing interest to the public. This book is a valuable resource, doubly so since the letters in this volume were written with no expectation that they would ever be published. Lines of Battle is an authentic sample of the firsthand accounts left by the servicemen who actually experienced World War II, a book of vivid descriptions and significant insights written as the war unfolded. Through these letters, a reader can transport himself back in time and imagine himself following this story as the recipients must have. In this way, a reader gains insight to the persisting question: What was the American experience like?

Annette Tapert has arranged the letters chronologically and so the story told here and the conclusions one draws from it evolve in steps. The men who wrote home individually describe episodes, rarely touching on the large aspects of the war. Philosophical passages multiply in the closing days of the war as weariness sets in, but American aims in World War II, never systematically spelled out by Roosevelt, are not articulated boldly here. Indeed, in the early years of this story, it seems as though Americas war effort simply happened, that it was action preceding thought, rather than action based on firm ideas. But this is hard to reconcile with the sheer immensity of the war effort, in which eleven million servicemen crossed two oceans to fight the Axis powers at points separated by twelve thousand miles.

Why did America fight? There is no evidence here that American soil was threatened, or that an accommodation with the Axis, advocated in 1941 by the America First movement, was impossible. It becomes apparent that American motives were political, a fact that distinguishes the perspective of the American soldier from his British, French, German, or Russian counterparts, all of whom waged struggles close to home for the very existence of their countries.

As the story unfolds, the reader sees in these letters a deep appreciation for Americas standing in the world and her responsibilities, a discovery which belies caricatures of the American GI as unfeeling or belatedly informed after the fact. Plainly, America did not seek direct involvement in the war; in time, however, Americans found that they could not justify abstention in a conflict in which America had the power to influence the outcome in favor of her friends. In these letters, one encounters the dismay felt by Americas soldiers about home-front complacency and the tendency toward national selfishness which almost kept the U.S. out of war, which undermined conduct of the war and threatened to resurface as the war ended. But the soldiers in this book did not question that America had to stand up and be countedwhat they wanted were weapons, support, and assurances that the life they returned to would resemble the life they left behind. This was perhaps best put in a letter by Lieutenant Charles Leiber of the 34th Infantry Division written on the eve of his death in the American advance into Bologna. Why we fight has been a topic for all of us to ponder, he wrote. All one has to do is to look at Italy to appreciate all the good things at home. I like to feel I am fighting for the privilege of enjoying all that we as a people have been blessed with.