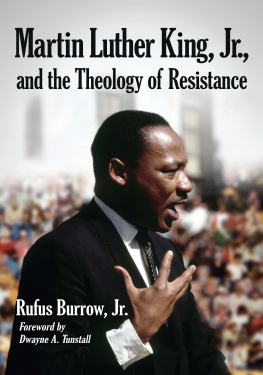

The Critique of Nonviolence

Martin Luther King, Jr., and Philosophy

Mark Christian Thompson

Stanford University Press

Stanford, California

STANFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS

Stanford, California

2022 by Mark Christian Thompson. All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system without the prior written permission of Stanford University Press.

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free, archival-quality paper

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Thompson, Mark Christian, author.

Title: The critique of nonviolence : Martin Luther King, Jr., and philosophy / Mark Christian Thompson.

Description: Stanford, California : Stanford University Press, 2022. | Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021045650 (print) | LCCN 2021045651 (ebook) | ISBN 9781503631137 (cloth) | ISBN 9781503632073 (paperback) | ISBN 9781503632080 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: King, Martin Luther, Jr., 1929-1968Philosophy. | RacePhilosophy. | Nonviolence--Philosophy. | Ontology. | African American philosophy. | Philosophy, German. | African AmericansCivil rights.

Classification: LCC E185.97.K5 T455 2022 (print) | LCC E185.97.K5 (ebook) | DDC 323.092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045650

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021045651

Cover art: Robert Motherwell, In Plato's Cave No. 1, 1972. Acrylic on canvas, 182.9 x 243.8 cm (72 x 96 in.)

Typeset by Newgen in Minion Pro 10/15

For my wife, Kerri

Love is an ontological concept. Its emotional element is a consequence of its ontological nature. It is false to define love by its emotional side. This leads necessarily to sentimental misinterpretations of the meaning of love and calls into question its symbolic application to the divine life. But God is love. And, since God is being-itself, one must say that being-itself is love.

Paul Tillich (Systematic Theology, Volume One 1951, 279)

Table of Contents

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank everyone at Stanford University Press who read and worked on this book. I am particularly grateful to Erica Wetter and Kate Wahl for their interest and belief in the project, and to two anonymous readers for their encouraging and illuminating reviews. I thank early readers Nan Z. Da and Anahid Nersessian for their invaluable input, along with my colleague Jeanne-Marie Jackson for her continual support. As always, I give my deepest thanks to my wife and children for making this book possible in the most fundamental way.

Introduction

Ontology and Nonviolence

I. Kings Black power

WHAT IS BLACK POWER? On June 16, 1966, in the wake of the James Meredith shooting, Stokely Carmichael publicly announced his preliminary formulation of Black Power, which he continued to refine for years after. It was an occasion Martin Luther King, Jr. recalled with great restraint in Where Do We Go from Here: Chaos or Community? (originally published in 1967), given that Carmichael admitted to having used him to gain the widest audience possible for the announcement. Representing the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), King, along with Carmichael, then chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and Floyd McKissick, the national director of the Congress of Racial Equity (CORE), organized a joint march meant to continue activist James Merediths solitary March Against Fear. In the wake of the Voting Rights Act (1965), Meredith had set out to walk from Memphis, Tennessee, to Jackson, Mississippi, to rally Blacks to vote. He was shot June 6, 1966the second day of his march. Having survived the attempt on his life, Meredith remained hospitalized as the SCLC, SNCC, CORE, and any other Civil Rights organization that would join, immediately continued his journey, now dubbed Merediths Mississippi Freedom March.

Once during the afternoon, King recounts,

we stopped to sing We Shall Overcome. The voices rang out with all the traditional fervor, the glad thunder and gentle strength that had always characterized the singing of this noble song. But when we came to the stanza which speaks of black and white together, the voices of a few of the marchers were muted. I asked them later why they refused to sing that verse. The retort was: This is a new day, we dont sing those words any more. In fact, the whole song should be discarded. Not We Shall Overcome, but We Shall Overrun. As I listened to all these comments, the words fell on my ears like strange music from a foreign land. My hearing was not attuned to the sound of such bitterness. I guess I should not have been surprised. I should have known that in an atmosphere where false promises are daily realities, where deferred dreams are nightly facts, where acts of unpunished violence toward Negroes are a way of life, nonviolence would eventually be seriously questioned. I should have been reminded that disappointment produces despair and despair produces bitterness, and that the one thing certain about bitterness is its blindness. Bitterness has not the capacity to make the distinction between some and all. When some members of the dominant group, particularly those in power, are racist in attitude and practice, bitterness accuses the whole group. (King 2010a, 182)

Stunned by the sound of this strange music from a foreign land, King seeks to decipher this new musical language in conversation with Carmichael. It is then King realizes that Carmichael has used him to announce the Black Power slogan to mainstream America, and the world. Carmichael admits to his ruse and rejects nonviolence, calling the new movement Black Power after refusing in private Kings request he use some less aggressive alternative.

The fact that Martin Luther King, Jr. suggested names for Black Power to Stokely Carmichael may seem odd. How can there be racial communities in the absence of essential difference, where race is not a matter of ideological and historical contingency? Once Black political and economic power is amassed and equality achieved, will race disappear from American society?

In other words, Black Power intellectuals including King did not present a systematic understanding of racial ontology. That is, they did not explicitly ask, what is the being and end of race? What is the being and end of Blackness? What is racial being and what are the ends of race? Of course, it is perfectly understandable they did not. With more practical matters in mind and a wider public to reach, Black Power leaders did not bother to expound theories of gnostic being and eschatological end. Nevertheless, they could engage in high theory in public speeches, meetings, and writings; among Black radicals, reading philosophy and philosophizing were thought crucial to understanding racism.

Additionally, when they posited Black community in the face of white supremacy, Black radicals made philosophic decisions to clarify their practical aims. Although concerned with the material means and ends of racial oppression, their mode of apprehending racisms concrete causes and conditions identifies race as a naturalized (when not natural) phenomenon. Rarely distinguishing between race as a construct and race as a metaphysical truth, many Black radical thinkers of the period left ambiguous how they understood Blackness ontologically, as either a cause, product, or event. Indeed, their conceptual separation of Black and white went beyond race as the ideological imposition of white supremacy, implying instead a metaphysical force. In this understanding, races teleological unfolding has been either unjustly altered or is about to undergo revolutionary change according to a greater plan of justice. In other words, even though Black Power thinkers do not overtly describe a racial ontology, they nevertheless still possess one, both as an effect of the philosophical tradition in which they intervened and as a condition of their practical analyses of racial oppression.