IMAGES

of America

REMEMBERING

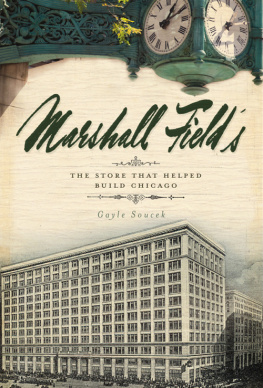

MARSHALL FIELDS

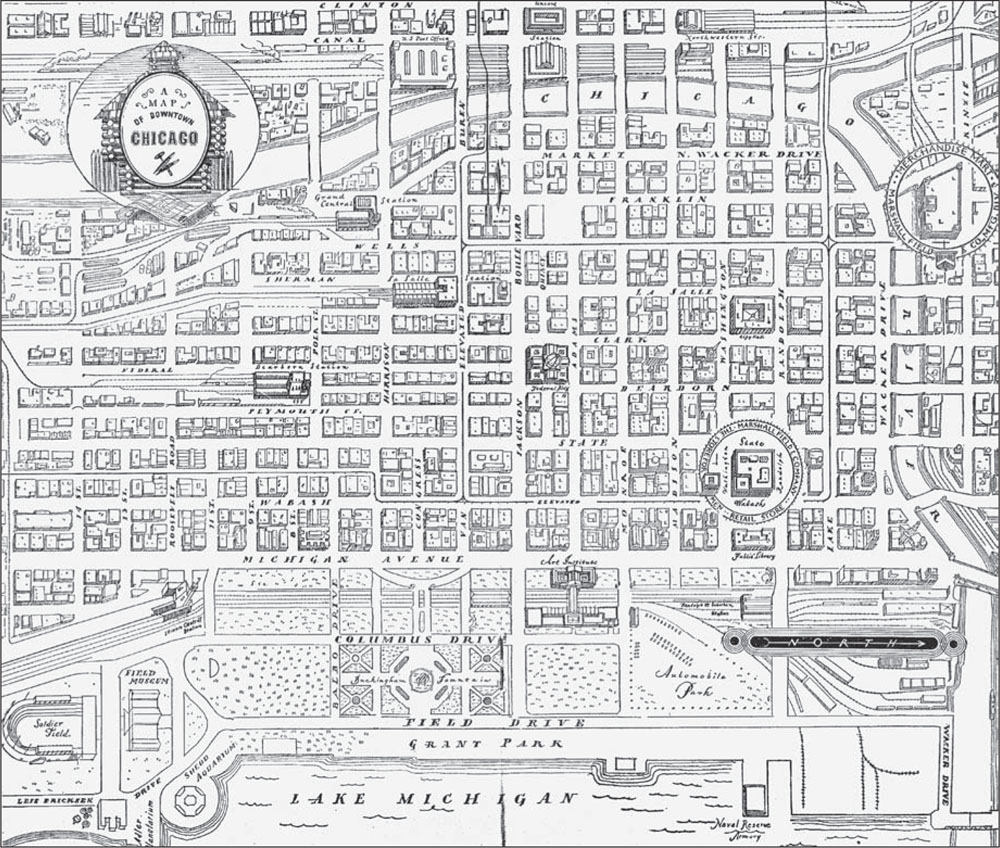

Marshall Field & Companys retail store (center right, circled) stood at the nucleus of Chicagos booming downtown Loop district in 1946. At this point, the 94-year-old company was the biggest department store in the Midwest and as famous nationally as Chicagos stockyards. The company no longer owned the Merchandise Mart (upper right, also circled), but still maintained space there for merchandise from its manufacturing division. (Authors collection.)

ON THE COVER: A bustling crowd converges outside Marshall Field & Company during the holiday season of 1938. At this point, the store had 234 selling sections, 45 passenger elevators, and 7,500 employees serving 65,000 customers daily (up to 200,000 on special occasions). Together, the 13-story main building, along with the six-story Store for Men on an adjacent corner covered approximately one-and-a-quarter city blocks with just over 61 acres of retail floor space. (Courtesy Chicago History Museum, ICHi-59534.)

IMAGES

of America

REMEMBERING

MARSHALL FIELDS

Leslie Goddard

Copyright 2011 by Leslie Goddard

ISBN 978-0-7385-8368-6

Ebook ISBN 978-1-4396-7057-6

Published by Arcadia Publishing

Charleston, South Carolina

Library of Congress Control Number: 2010939829

For all general information, please contact Arcadia Publishing:

Telephone 843-853-2070

Fax 843-853-0044

E-mail

For customer service and orders:

Toll-Free 1-888-313-2665

Visit us on the Internet at www.arcadiapublishing.com

To Douma and Boppa, who introduced me to Marshall Fields; to Meme,who made that love a family tradition; and to Bruce, my dearest friend

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

When dealing with a department store that existed for 153 years, employed thousands, and sold to millions, the challenge is sifting through thousands upon thousands of photographs, advertisements, promotional items, and personal memories. In the case of Marshall Fields, a store that inspired passionate devotion, the chore is that much more challengingand rewarding.

I am indebted to the Chicago History Museum (CHM), whose collections include a vast quantity of Marshall Fields materials. Without the assistance of CHM staffers, including Lesley Martin, Erin Tikovitsch, Elizabeth Reilly, and Leah Recht, this book would not have been possiblefor their help I am immensely grateful.

Collections at other archives, libraries, and companies enrich our understanding of this remarkable store. Special thanks go to Morag Walsh and Sarah Zimmerman at the Chicago Public Library, Danielle N. Kramer at the Ryerson and Burnham Libraries at the Art Institute of Chicago, Jane Nicoll at the Park Forest Historical Society, Jane Rozek at the Schaumburg Township District Library, Lori Osborne and Eden Juron Pearlman at the Evanston History Center, Pat Barch at the Hoffman Estates Museum, Dave Gregoire at Those Funny Little People Enterprises, Inc., Deanna Boss at the Maccabee Group, and Nancy Wilson at the Elmhurst Historical Museum.

Many individuals made this book possible by digging through their own photograph albums and indulging me in long conversations about the past. Thank you for generously sharing your memories with us.

I also need to thank Melissa Basilone, my talented and supportive editor at Arcadia Publishing, and John Pearson, Arcadias Midwest publisher. Ann Wendell, whose history of Frederick & Nelson inspired me, generously shared advice that steered my course.

My mother, Carol Goddard, and my sister, Laura Amann, provided early encouragement and steadfast support, while my nieces Elizabeth, Caroline, and Anna renewed my love for the Walnut Room, willingly helped with photographs, and listened to endless stories. Finally, to my husband, Bruce Allardice, thank you from the bottom of my heart for your expert guidance and your dogged encouragement, without which this book would not have been possible.

Where not otherwise indicated, images are from the authors collection.

INTRODUCTION

In the pantheon of American department stores, few names loom larger than that of Marshall Field & Company. Macys and Hudsons might have been bigger, and A.T. Stewart earlier, but few department stores could match Fields for elegance, quality, luxury, and service.

When I was a little kid, I had this sense of awe whenever I went there, said cultural historian and author David Garrard Lowe. And when the Fields van came to your house to deliver something, that was an event. Nearly everyone who grew up in the Chicago area in living memory went to see the Marshall Fields holiday windows at least once. The words fourth-floor toy department still ring magically in the ears of many Chicagoans, and the stores huge bronze clocks have been rendezvous spots for more than a century. For its entire history, the stores stately granite retail building with its four grand entrance columns required no large sign, just discrete plaques set into the corners.

What distinguished Marshall Field & Company from the dozens of other stores stretching up and down Chicagos State Street shopping district in its heyday? How did this retailer earn its place as Chicagos leading department store and one of the top merchandisers in the world?

To understand that, we must go back to 1852, a time when Chicago had barely 30,000 residents and Marshall Field, the teenage son of a farmer, was clerking at a dry goods store in rural Massachusetts, little dreaming of Chicago.

That year, however, a remarkable young New Yorker named Potter Palmer stepped off the train in Chicago. Amidst the muddy streets and ramshackle wooden buildings, Palmer saw opportunity. This vigorous city, despite its youth and rough edges, had energy, an exceptional location, and the potential to become the countrys greatest mercantile hub. Palmer abandoned plans to head farther west and opened a dry goods business on Lake Street, then Chicagos leading commercial district.

Palmer instituted many policies for which Marshall Fields would become famous. Borrowing ideas from New York dry goods pioneer A.T. Stewart (who in turn borrowed from the Bon March in Paris), he set fixed prices on his goods, displayed merchandise attractively, undersold his competitors on selected items, and stocked his store with both modestly priced wares and luxury merchandisefine silks, soft woolens, sturdy cottons, and lace goods. Most importantly, he accepted returns for any reason, at a time when most merchants refunded money only if the goods arrived damaged. Palmer did not invent the one-price, no-haggle system or the satisfaction guarantee, but he did make them fundamental to his business.

What began as a 20-by-160-foot, retail-only shop became, within 13 years, one of Chicagos leading wholesale and retail dry goods businesses. When Palmer decided to sell, he turned to two energetic young men at a competing dry goods firm: Marshall Field, who had arrived in Chicago in 1856, and finance wunderkind Levi Leiter. Field and Leiter took up the offer, and in 1865, the firm of Field, Palmer & Leiter was launched. Palmer and his brother Milton stayed on as partners.

While the economic conditions of the postwar years tested the young company, Marshall Field and Levi Leiter were able to buy out the Palmers in 1867 and reorganize as Field, Leiter & Company. The partners continued many policies, especially the targeting of the wives and daughters of Chicagos newly wealthy. Field moved to New York City so he could oversee purchasing, selecting stylish products to appeal to those prosperous customers who were known as the carriage trade.

Next page