Bibliography and Suggested Reading

Bordewich, Fergus. Washington: The Making of the American Capital. New York: Amistad (Harper-Collins), 2008.

Boundary Stones of the District of Columbia, www.boundarystones.org.

Carrier, Thomas J. Washington, DC: A Historical Walking Tour. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2005.

Gilmore, Matthew. A Timeline of Washington DC History. H-Net: Humanities and Social Sciences Online. www.h-net.org/~dclist/timeline1.html

Gutheim, Frederick. Worthy of the Nation: Washington, DC, from LEnfant to the National Capital Planning Commission. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2006.

Heritage Preservation Services, American Battle-field Protection Program. Fort Stevens, Civil War Sites Advisory Commission Battle Summaries, www.nps.gov/hps/abpp/battles/dc001.htm.

The Historical Society of Washington, DC DC History Resources, www.historydc.org/resources/.

Minetor, Randi S. Passport To Your National Parks Companion Guide: National Capital Region. Guilford, Conn.: The Globe Pequot Press, 2008.

Mitchell, Alexander D. Washington, DC, Then and Now. San Diego, Calif.: Thunder Bay Press, 1999.

National Park Service Web site, www.nps.gov.

National Register of Historic Places website, www.nps.gov/nr.

Solomon, Mary Jane, Barbara Ruben, and Rebecca Aloisi. Insiders Guide: Washington, DC Guilford, Conn.: The Globe Pequot Press, 2007.

Standiford, Les. Washington Burning: How a Frenchmans Vision for Our Nations Capital Survived Congress, the Founding Fathers, and the Invading British Army. New York: Crown Publishing Group, 2008.

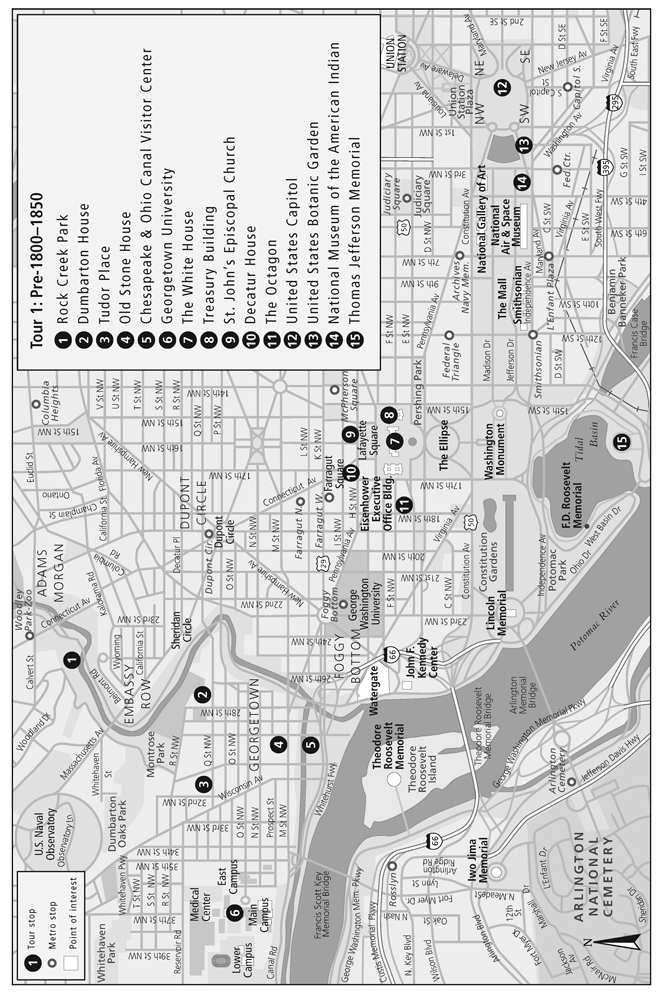

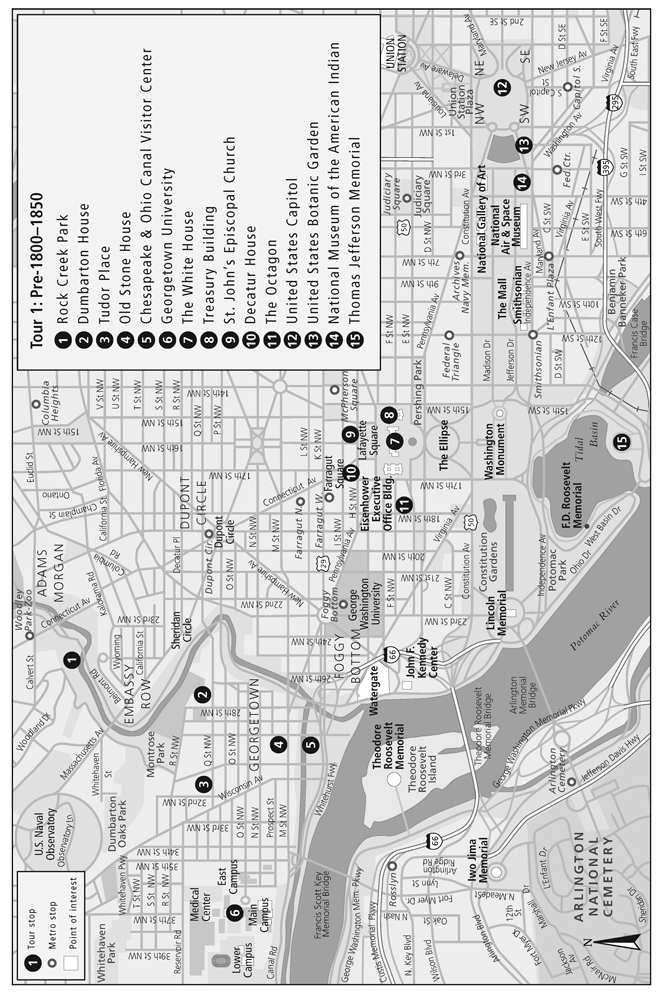

Tour 1: Pre-18001850

Washington: The End of the Manors, the Beginning of a Nation

In 1790, when George Washington chose this diamond-shaped slice of land to become the site of the nations capital, this territory was divided into a network of manor houses and estates, farmed by slaves. Here at the intersection of the Potomac and Eastern Branch Rivers, colonists were attracted to the farthest point to which large ships could navigate up the Potomac. There they established an early settlement, formalizing it as Georgetown in 1751. The new town quickly became an inland center of trade and commerce.

Once construction of the nations capital city began, residents recognized the arrival of a period of considerable change throughout this corner of Maryland and Virginia. Landowners with large estates objected strongly to the purchase of their land for creation of a city, finally agreeing to an arrangement through which they would keep half their land, while the government would pay a fair price for the rest. Washington brought Pierre LEnfant to the table to begin the grand plan for the majestic capital city, while Andrew Ellicott and Benjamin Banneker set up the forty sandstone markers that delineated the boundaries of the capital district.

Despite the urgent need for a capital city, the fledgling capital did not receive adequate financial support from Congress to grow and flourish from the outset. LEnfant was forced to abandon his project just ten months after he began it, when he met resistance to completing the entire design from the commissionersThomas Jefferson, Daniel Carroll, and David Stuart. By the time the Presidents House and Capitol Building were ready for occupancy in 1800, only a fraction of LEnfants grand plan was in place, the rest of it either under construction or shelved until additional funds could be acquired.

One wing of the Capitol only had been erected, which with the Presidents House, a mile distant, both constructed with white sandstone, were shining objects in dismal contrast with the scene around them. Instead of recognizing the avenues and streets portrayed in the plan of the city, not one was visible, unless we except a road with two buildings on each side of it called the New Jersey Avenue. The Pennsylvania Avenue, leading as laid down on paper, from the Capitol to the Presidents Mansion, was then nearly the whole distance a deep morass, covered with alder bushes.... The roads in every direction were muddy and unimproved.... In short, it was a new settlement.

John Cotton Smith, member of Congress from Connecticut in the Sixth Congress

How to Find the Four Original Cornerstones

To the south: The marker is at Jones Point Lighthouse in Alexandriain an opening in the seawall, where the stone was hidden until 1912.

To the west: Andrew Ellicott Park at 2824 N. Arizona Street, south of West Street in Falls Church, Virginia, has the second marker.

To the north: The marker resides at the west corner of Arlington County, at the 1880 block of the East-West Highway in Silver Spring, Maryland, just south of the highway at the edge of a forest.

To the east: Find the marker between Seat Pleasant and Capitol Heights, about 100 feet east of the intersection of Eastern and Southern Avenues.

Theres more information on the locations of all forty boundary stones at www.boundarystones.org.

Meanwhile, rumblings of another war began to increase in volume as the nineteenth century began. The War of 1812 gained momentum until the English navy succeeded in reaching the capital city in August 1814, and while First Lady Dolley Madison quickly thought to rescue the artwork, members of Congress secured the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, keeping them safe while the British set fire to the city. In one day, on August 24, the British burned the War Department, the Treasury Building, the Presidents House, and the Capitoland they would have left nothing but charred remains, had it not been for a driving rain that fell that night, drenching the burning buildings and quenching the fire.

As reconstruction began, workmen had no choice but to paint the burnt-black Presidents House with white paint, changing its appearance so completely that area residents began to call it the White House. (President Theodore Roosevelt would officially rename the building the White House in 1901.)

The sky was brilliantly illuminated by the different conflagrations, and a dark red light was thrown upon the road, sufficient to permit each man to view distinctly his comrades face.... When the detachment sent out to destroy Mr. Madisons house entered his dining parlor, they found a dinner table spread and covers laid for forty guests.... They sat down to it,... and, having satisfied their appetites with fewer complaints than would have probably escaped their rival gourmands, and partaken pretty freely of the wines, they finished by setting fire to the house which had so liberally entertained them.

George Robert Gleig, a British soldier who participated in the attack on Washington, August 24, 1814

With the war ended and a new sense of optimism bubbling throughout the country, Washingtons development could move forward again. Construction began on the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which would bring raw goods and products from the nations interior states to the capital, cementing Washingtons place as a national port and commercial center. As the canal neared its final length, however, the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad arrived in Washington, opening the city to an unprecedented level of commercial activityand signaling the slower canal routes imminent decline.

Begin your tour of Washingtons earliest days in Georgetown, where many historic sites hearken back to the late 1700s and early 1800s. Youll find a fascinating contrast between wealthy, genteel landowners lives and the simple home of a local carpenter, as well as the beginnings of commercial activity that would grow to place Washington at the heart of international trade, making the city a conduit to the nations interior states and a hub of daily market activity.