The Language of Fruit

PENN STUDIES IN LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE

John Dixon Hunt, Series Editor

This series is dedicated to the study and promotion of a wide variety of approaches to landscape architecture, with special emphasis on connections between theory and practice. It includes monographs on key topics in history and theory, descriptions of projects by both established and rising designers, translations of major foreign-language texts, anthologies of theoretical and historical writings on classic issues, and critical writing by members of the profession of landscape architecture. The series was the recipient of the Award of Honor in Communications from the American Society of Landscape Architects, 2006.

THE

LANGUAGE

OF FRUIT

Literature and Horticulture

in the Long Eighteenth Century

Liz Bellamy

Copyright 2019 University of Pennsylvania Press

All rights reserved. Except for brief quotations used for purposes of

review or scholarly citation, none of this book may be reproduced in any

form by any means without written permission from the publisher.

Published by

University of Pennsylvania Press

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 191044112

www.upenn.edu/pennpress

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

A catalogue record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

ISBN 978-0-8122-5083-1

CONTENTS

Chapter 1. I Am the True Vine:

The Uses of Fruit in Biblical and Classical Tradition

Chapter 2. A Chiefe Meanes to Enrich This Common-Wealth:

The Language of Fruit in Horticultural Literature

Chapter 3. Stumbling on Melons:

Negotiating the Garden in Seventeenth-Century Verse

Chapter 4. You Have Only Squeezed My Orange:

The Fungibility of Fruit in Restoration Drama

Chapter 5. The Native Zest and Flavour of the Fruit:

Constructions of the Apple in Eighteenth-Century Georgic

Chapter 6. Unnatural Productions:

Cultivating the Pineapple in the Romantic Period Novel

In his Dialogue (or Familiar Discourse) and Conference between the Husbandman and Fruit-Trees (1676), the horticultural writer and successful nurseryman Ralph Austen advises his readers that they need to discourse with Fruit-trees having learned to understand their Language. He argues that, although this language is not Articulate and distinct to the outward sence of hearing in the sound of words, trees nonetheless speak plainly, and distinctly, to the inward sence, the understanding. This book can be read as a response to Austens injunction, since it aims to discourse with fruit trees, understand their language, and recognize how they communicate with our inward sense. It will explore the meanings of fruits and fruit trees by considering how they have been represented in texts across a period stretching from the Restoration to the Romantic era, or, roughly, from Ralph Austen to Jane Austen. The focus will be on how poets, playwrights, and novelists have deployed fruit in their works, and how they have responded to changes in cultivation techniques, the range of available varieties, and mechanisms for the exchange and distribution of fruit.

Of course, literary depictions cannot be read as direct and unproblematic reactions to developments in fruticultural practice. Fruit has so many symbolic associations that its portrayal is inevitably inflected by inherited topoi, cultural resonances, and stories, which all shape how it is perceived and how it functions within a text. Representations are also influenced by cultural codes embedded within the formal conventions of different genres or discourses. These factors of stasis or tradition interact with horticultural innovations to ensure that change is interpreted through a lens of inherited assumptions. To achieve Austens aim of allowing fruit to speak directly to our understanding, we need to explore the meanings accruing to fruit in the early modern period and how these meanings are articulated within a range of forms. This will involve not only the biblical sources that feature in Austens dialogues, with the story of

Fruit is freighted with symbolism derived from its physical form and its origins in sexual reproduction as well as its literary heritage. Its swelling and ripening can represent female fecundity and fruitfulness as well as male sexuality and tumescence. Sexual maturity or availability can be expressed in terms of ripeness and those who have not reached this condition may be identified as green or unripe fruit. The loss of virginity is suggested by the plucking and biting of fruit, particularly the cherry, and some of these associations have continued to the present day. Particular body parts can be identified with specific fruits: female buttocks and breasts with peaches and melons; male genitals with pears, plums, and nuts, as well as with wrinkly dried fruits such as apricots and raisins. The literary representation of fruit can thus be explored as an aesthetic negotiation of the links and boundaries between the figurative and the quotidian, inherited allusion and contemporary change at a time when Britain was developing the characteristics of a consumer society and an exchange economy.

The many references to fruit in literary texts indicate its importance in early modern society. Ken Albala suggests that Renaissance writings on health and regimen manifest a fear of fruits bordering on the pathological, yet the centrality of orchard fruits within British cuisine is evident from early modern cookbooks, with numerous recipes for stewing and baking but also pickling and preserving apples and pears, as well as hardy stone fruits like cherries, plums, and damsons.

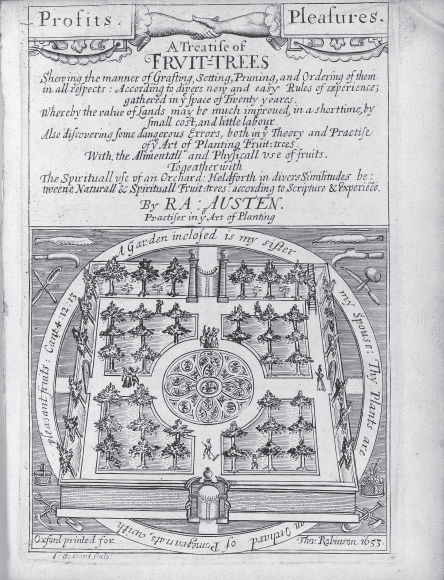

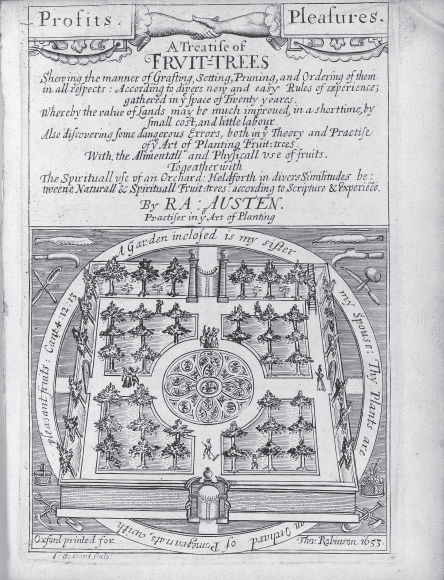

Figure 1. Ralph Austen, A Treatise of Fruit-Trees (Oxford: Printed for Tho. Robinson, 1653), title page, showing the significance of biblical references within practical gardening tracts.

Fruit thus encompassed both the hardy and abundant orchard crops consumed by the lower classes and the delicate produce of the kitchen garden, reared with intensive labor and care for the tables of the affluent, furnishing metaphors that could be appropriated for the representation of different social groups.

John Parkinson lists twenty-one different varieties of peach in his 1629 Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris (Park-in-Suns Earthly Paradise), commenting that Their varieties are many, and more knowne in these dayes then in former times (580). Some of the new fruits were hardier than their predecessors and more able to withstand the British climate, some had new flavors or culinary applications, and some had different flowering and fruiting patterns, making it possible to extend the period of harvest. This was part of a growing enthusiasm for the cultivation of out-of-season fruits in the hope of limiting the period in which fresh fruits were unavailable. Improvements in the technology of hotbeds and the subsequent development of hothouses were likewise associated with the drive to extend the fruiting season and these innovations eventually encouraged attempts to cultivate more exotic fruit trees, such as the subtropical citrus. This culminated in the eighteenth century in the production of tropical fruits such as pineapples and mangoes. There was thus a progressive extension of the types of fruit that could be raised in Britain, as well as improvements in cultivation techniques and fruticultural equipment, with increasing emphasis on human intervention and the control or mastery of nature.

Next page