Routledge Library Editions

THREE STYLES IN THE STUDY

OF KINSHIP

ANTHROPOLOGY AND ETHNOGRAPHY

Routledge Library Editions

Anthropology and Ethnography

FAMILY & KINSHIP

In 7 Volumes

| I | Three Styles in the Study of Kinship | Barnes |

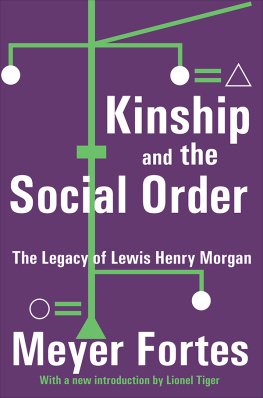

| II | Kinship and the Social Order | Fortes |

| III | Comparative Studies in Kinship | Goody |

| IV | Elementary Structures Reconsidered | Korn |

| V | Remarks and Inventions | Needham |

| VI | Rethinking Kinship and Marriage | Needham |

| VII | A West Country Village: Ashworthy | Williams |

THREE STYLES IN THE

STUDY OF KINSHIP

J A BARNES

First published in 1971

Reprinted in 2004 by

Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon, OX 14 4RN

Transferred to Digital Printing 2006

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group

1971 J A Barnes

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or

reproduced or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical,

or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including

photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval

system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

The publishers have made every effort to contact authors/copyright

holders of the works reprinted in Routledge Library Editions -

Anthropology and Ethnography. This has not been possible in every case,

however, and we would welcome correspondence from those

individuals/companies we have been unable to trace.

These reprints are taken from original copies of each book. In many

cases the condition of these originals is not perfect. The publisher has

gone to great lengths to ensure the quality of these reprints, but wishes

to point out that certain characteristics of the original copies will, of

necessity, be apparent in reprints thereof.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Three Styles in the Study of Kinship

ISBN 978-0-415-33008-4

ISBN 978-1-136-53500-0 (ePub)

Miniset: Family & Kinship

Series: Routledge Library Editions Anthropology and Ethnography

Printed and bound by CPI Antony Rowe, Eastbourne

Three Styles in the

Study of Kinship

J. A. Barnes

First published in 1971

by Tavistock Publications Limited

II New Fetter Lane, London E.C.4

SBN 422 73820 4

J. A. Barnes 1971

To Frances

Part of was written during 1965-1966 while I was in Churchill College, Cambridge, as an Overseas Fellow. I am much indebted to the Master, the late Sir John Cockcroft, and to the Fellows of the College for their hospitality. The greater portion of the book was written at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Australian National University. I am grateful for this opportunity to record my deep appreciation of the stimulus derived from participation in the vigorous intellectual life of the Institute. I am also very conscious of the ample provision of time and facilities for scholarship which made work in the Institute so pleasurable. I was greatly helped and encouraged by Anne-Marie Johnson and owe much to the comments made on early drafts of portions of the book by my colleagues Paula Brown Glick and L. R. Hiatt. I wish to thank the Faculty of Economics and Politics, University of Cambridge, for assistance in preparing the final typescript.

Most books on kinship contain descriptions of selected social institutions - families, marriage patterns, clans and lineages, kinship terminology, and so on. There are no descriptions of this kind here. This book is on the study of kinship, not on kinship itself. The reader primarily interested in kinship, or in some similar substantive division of social and cultural behaviour, may well ask what need is there for a book whose subject-matter stands at one or more removes from the empirical world. I therefore begin with an attempt to explain and justify what I am trying to do.

This extended analysis of the writings of three anthropologists, Murdock, Lvi-Strauss, and Fortes, in the field of kinship was begun in an effort to assist the transformation of social anthropology from an intuitive art to a cumulative science. For several decades sociologists and social anthropologists have maintained as an article of faith that their dual discipline aims at the discovery of social laws, at the formulation and validation of significant generalizations about culture and society. I have no quarrel with this article of faith but find it chronically embarrassing to have to present such an apparently meagre set of works as our only claim to scientific salvation. In social science there are plenty of high-level tautologies masquerading as laws, and innumerable low-level generalizations which stand up well to test but which cannot readily be linked together in an embracing logical scheme. There are taxonomies galore, many of which sharpen our vision and enable us to see contrasts and connexions previously overlooked. But taxonomies in social science, unlike those in evolutionary biology, have no temporal implication and cannot be proved or disproved, only used or discarded.

There are many people who maintain that this state of affairs is inevitable. Man, they say, is born free, unlike the atom. There is no inexorable regularity in human affairs, and the only generalizations possible about social life are merely statistical summaries of past events, with no predictive power. Other people argue that the fault lies in the phenomena we chose to generalize about. We are too much concerned with accidental features that are the result of specific historic sequences, whereas if only we were to shift to using broad enough categories, everything really significant would be explained by ethology, general systems theory, or something similar. There is merit in both these views. On the one hand the laws of social science must necessarily be of a different order from the laws of physics, if only for the reason that men modify their behaviour in the light of knowledge of the laws to which it is supposed to conform, whereas the planets continue in their courses in blissful ignorance of whether Ptolemy, Newton, or Einstein wears the mantle of orthodoxy. On the other hand brains, men, and societies are nothing but gigantic configurations of law-abiding atoms. It is scarcely surprising that at a sufficiently empty level of generality there are similarities in all thoughts, all systems of interaction and symbolic interchange, all mammalian behaviour, all primate societies, and so on. Indeed, these two contrasted criticisms pose problems for social science that will become more acute in the future. We need to know to what extent the generalizations of social science are self-negating or self-fulfilling prophecies. Once we know how the system works, we think we also know how to make it work differently, and on the other hand, once the mode and mean are published, they become available as approved norms, as for example with Kinsey, so that