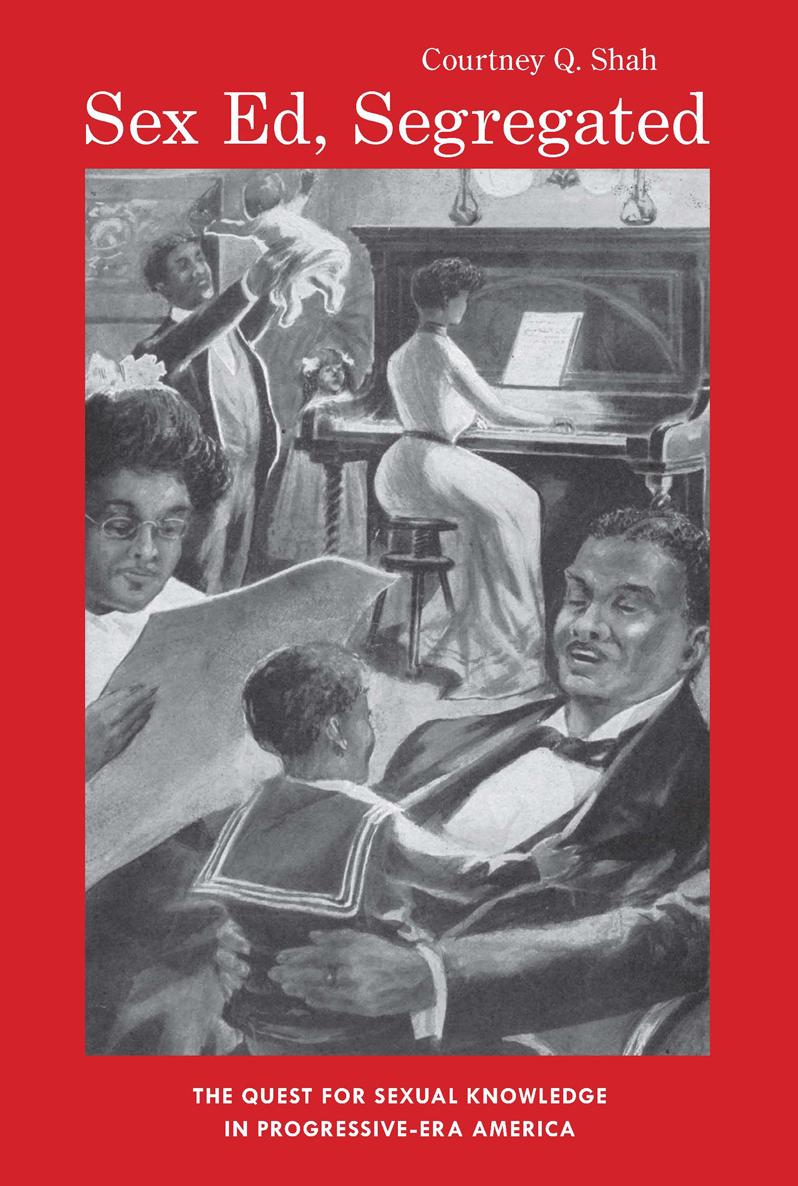

Against the backdrop of the Progressive Era, World War I, and the 1920s, sex education burgeoned in the United States through institutions like the YMCA, the popular press, girls schools, and the US military. As access to sexual knowledge increased, reformers debated what the messages of a sex-education curriculum should be and, perhaps more important, who would receive those messages.

Courtney Shahs study chronicles this debate, showing that sex education then, just as in our own era, had as much to do with politics and morals as it did with biology and medicine. Examining how different population groups in the United States were given contrasting types of sex education, Shah demonstrates that such education was used as a tool to reinforce or challenge racial segregation, womens rights, religious diversity, and class identity.

Courtney Shah is an instructor of history at Lower Columbia College in Longview, Washington.

[Shah] exposes ways that whiteness denoted purity and middle-class respectability, excluding racial minorities, the working class, and poor, rural, and Southern populations from many reform efforts. Recommended. CHOICE.

Gender and Race in American History

Alison M. Parker, The College at Brockport,

State University of New York

Carol Faulkner, Syracuse University

The Men and Women We Want

Jeanne D. Petit

Manhood Enslaved:

Bondmen in Eighteenth- and Early Nineteenth-Century New Jersey

Kenneth E. Marshall

Interconnections:

Gender and Race in American History

Edited by Carol Faulkner and Alison M. Parker

Susan B. Anthony and the Struggle for Equal Rights

Edited by Christine L. Ridarsky and Mary M. Huth

The Reverend Jennie Johnson

and African Canadian History, 18681967

Nina Reid-Maroney

Sex Ed, Segregated:

The Quest for Sexual Knowledge in Progressive-Era America

Courtney Q. Shah

Contents

Acknowledgments

I could not have completed this book without the support and assistance of many people. My first and principal debt is to Dr. Landon R. Y. Storrs, who advised me throughout my graduate career and beyond. Thank you to the University of Rochester Press, particularly Sonia Kane, Alison M. Parker, and Carol Faulkner, as well as my anonymous readers, who provided invaluable critiques of my manuscript and pushed me to think more deeply and produce a stronger work.

Many colleagues near and far shaped my thinking through coursework, conversation, and collegiality. Roberta Bivins, Kathleen Brosnan, Sarah Fishman, Karl Ittmann, Jacqueline Jones, Jane Kamensky, Craig Livingston, Steven Mintz, Martin Pernick, Joseph Pratt, Helen K. Valier, Eric Walther, and Michael Willrich each contributed in their own ways. I am grateful for the inestimable gift of my writing sisterhood! Marjorie Denise Brown, LaGuana Gray, Theresa Jach, and Angela Murphy provided emotional as well as intellectual support. They contributed suggestions on manuscripts, supportive emails, and lunches out so that none of us would become isolated and buried in our work. Emily Straus told me I could (and should) publish the book and continues to take good care of me from afar. In addition, Sonia Hernandez, Clayton Lust, and Albert Rodriguez provided a sounding board at critical moments in the process. My colleagues in the Department of Social Sciences at Lower Columbia College, especially Dennis Shaw, provided valuable support. Kristy Thompson and Neel Mehta read parts of the manuscript and provided me access to the American Film Institute silent film database. Maulin Shah enabled my work throughout the process.

The Department of History at the University of Houston assisted me through its generous financial support in the form of a King Fellowship and a Murry Miller travel grant to complete my research. I would like to thank the University of Minnesota for the Clarke Chambers Fellowship and David Klaassen and his staff at the Social Welfare History Archives for their expert assistance during my research trip. Lower Columbia College provided a travel grant, enabling me to present at the Organization of American Historians conference, which reinvigorated the project. I would also like to thank the Houston Academy of Medicine library, Bexar County Clerk Gerry Rickhoff and his staff at the Bexar County Courthouse, and the staff at the Institute of Texan Cultures at the University of Texas at San Antonio. The wonderful people at the University of Houston interlibrary loan department allowed me to access a wide range of materials from across the nation. I would like to thank the staff of Portland State University Millar Library and the Lower Columbia College Library for their assistance. And I thank the University of Texas Press for their permission to reproduce in chapter 6 portions of my article Against Their Own Weakness: Policing Sexuality and Women in San Antonio, Texas, during World War I, Journal of the History of Sexuality 19, no. 3 (2010): 45882. 2010 by the University of Texas Press.

More personally, I want to express my gratitude to Camie Wilson, who takes wonderful care of my children (and me). Thank you to my parents, Jim and Maureen Forsloff, for supporting my education in every way. And last, to Maya and Kamran: Mama wrote a book!

Introduction

In 1903, concerned newlyweds or curious adolescents may have found themselves furtively reading advice manuals on courtship, marriage, and sex. A proper young African American lady may have received Golden Thoughts on Chastity and Procreation , written by a married couple in conjunction with a medical doctor, to learn the most healthful and responsible way to live her life. The book aimed to teach Victorian, middle-class sexual respectability. It included paradoxical messages on sexuality and procreation: Prudery says: Keep still; do not talk about our sexual natures. Duty says: Cry aloud; let the truth be known; publish it to the world; save the people from pollution and destruction; from death. God says: My people are destroyed for lack of knowledge.Hosea iv. 6. The book provided explicit discussion of puberty, sexual intercourse, reproduction, and venereal diseases (VD). It combined the science of the time with a solid moral and Christian justification. Sexual knowledge, it argued, was a blessing to both good health and morality.

But the story of Golden Thoughts was more complicated. On the other side of town, outside of the Jim Crow neighborhoods, white audiences could furtively read the same book, this time entitled Social Purity, or, the Life of the Home and Nation . Drawings of black families in one and white families in the other made clear who the intended audience was. It appeared that blacks and whites had much in common and faced many of the same difficulties, but book publishers and sex educators were determined to keep them separate. Why?

The titles themselves suggest racial assumptions. Golden Thoughts is far more euphemistic, stressing chastity and procreation as the main tenets of sexual education. The stress on chastity implies the politics of respectability, so crucial to black middle class status, and defines sexuality as procreative rather than pleasurable. Social Purity links this individual book to the emerging national social purity movement and indeed suggests the importance of the nation in its title. Readers of Social Purity could improve the life of the home and the nation, institutions to reproduce (white) American culture.

![Russell - On education [recurso electrónico]](/uploads/posts/book/137691/thumbs/russell-on-education-recurso-electro-nico.jpg)