First published 1997 by Westview Press

Published 2018 by Routledge

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1997 Taylor & Francis

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

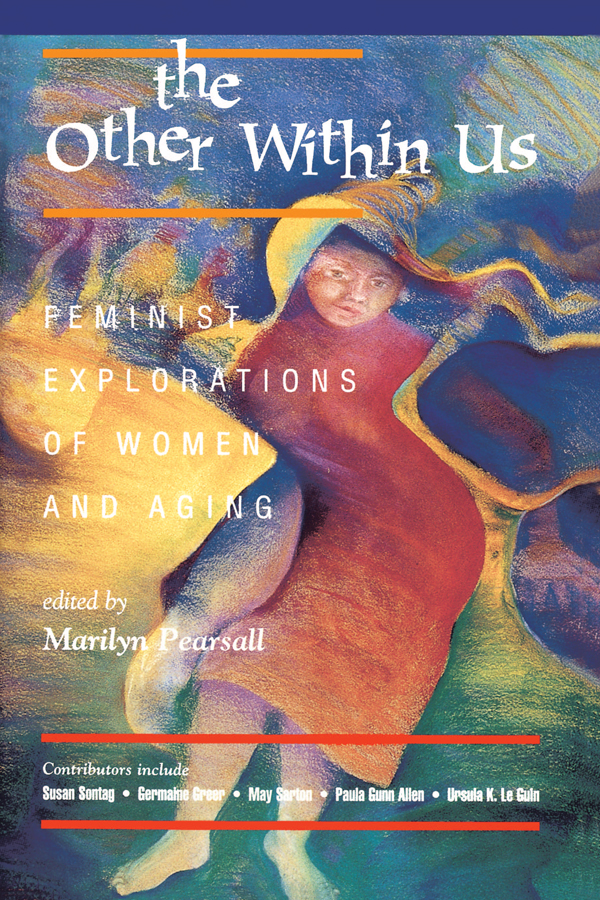

The other within us: feminist explorations of women and aging /

[compiled by] Marilyn Pearsall,

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 0-8133-8162-2 (hc).ISBN 0-8133-8163-0 (pbk.)

1. Gerontology. 2. Aging. 3. Feminist theory. I. Pearsall,

Marilyn.

HQ1061.087 1997

305.26dc21

96-47508

CIP

Design by Heather Hutchison

ISBN 13: 978-0-8133-8163-3 (pbk)

Marilyn Pearsall

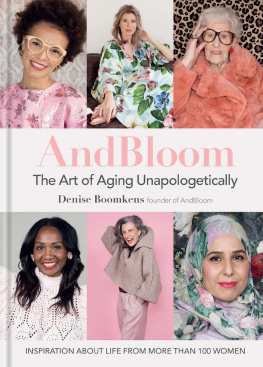

Looking in the mirror these days is not easy for most feminist women fifty years old or older who went through the second wave of the womens movement in the United States or Europe in the 1970s and 1980s. For years we have personally and politically critiqued the obsession with beauty and impossible body ideals that the media and advertisements lay on women. Many of us gave up various sorts of makeup and refused to shave our legs and underarms, and many stopped wearing high heels and short, tight skirts. However, now that we see our faces slowly assuming the visage of the older woman, our feminist rejection of beauty standards is put to its most exacting test. Can we resist being undermined by the lack of self-worth we feel when arriving, finally, at the most stigmatized stage in a womans life cycle: old age?

Part of the problem with aging from a feminist perspective is that as an issue it has been relatively neglected by contemporary feminism (is this denial, perhaps?). In any case, The Other Within Us redresses this omission by assembling essays that address the multifaceted collectivity of women and issues raised for them by the process of becoming old women.

This volume seeks to offer fresh paradigms to supplement, revise, and extend existing discoursesmedical, scientific, and social service orientedthat may be designated as gerontological. Feminist theorists deploying such discourses wish to dismantle the structure of their masculinist bias. Women in later life have been massively and familiarly objectified in gerontological literature. They have been negatively stereotyped both in popular writings and in media images. The term career path has been used to indicate the disciplinary technology that keeps the woman elder in her place. The chapters in this volume have been selected as situating, problematizing, and, above all, resisting that containment.

Women must undergo more than one process of becoming. According to Simone de Beauvoirs well-known dictum for the social construction of women as the second sex, One is not born, but rather becomes a woman. But as hard as it is to become a woman, it is even harder to become an old woman in patriarchal society. To undo the double process of objectification and self-objectification of women in these two social becomings, the chapters in this volume offer new paradigms to redescribe aging from a feminist perspective.

It may be helpful at this point to summarize de Beauvoirs description in The Second Sex of the social construction of the older woman. Parallel to her formulation of the becoming-woman is the leading idea of The Coming of Age, written some twenty years later, from which I draw the title of this collection: Within me it is the Otherthat is to say the person I am for the outsiderwho is old and that Other is myself. Together, these markers form an oblique entry into the chapters that follow on women and aging from a feminist perspective.

For these two discourses, the first on gender, the second on age, are mutually implicated. As Kathleen Woodward comments: Both books arose out of de Beau-voirs desire to write from the base of her own experience, which leads her unerringly to two of the most pressing social issues of our time: the subjection of women and the devaluation of the elderly. However, there is a hiatus both in time and in analysis in de Beauvoirs treatment of these two discourses. The relationship between the subjection of women and the devaluation of the elderly, between sexism and ageism, needs more development. Contemporary feminist theory seeks both to connect the two discourses of gender and age, of women and aging, and to show their imbrication with other categories such as race, class, sexuality, ethnicity, and nationality. The contributors to this volume eloquently attest to their commitment to this project. They respond to the feminist imperative to critique and challenge both the body in decline and the other within us.

The focus of the description of the older woman in The Second Sex is on the body in decline. Referring to the social construction of woman from maturity to old age, de Beauvoir proceeds from the phenomenology of becoming-a-woman. Her formulation rests on the existential grid of self and other. Each (human) consciousness, or self, according to her analysis, is fundamentaly hostile to every other consciousness. Each of us desires to be self, or essential being, and to make every other consciousness an inessential being, or other.

The groundbreaking application of this formulation in The Second Sex announces that man makes himself essential being, or self, and makes woman inessential being, or other; and woman becomes partially complicitous in the social construction of her otherness. As de Beauvoir comments: Now, what specifically defines the situation of woman is that shea free and autonomous being like all human creaturesnevertheless discovers and chooses herself in a world where men compel her to assume the status of the Other.

The social construction of femininity, or becoming-a-woman, establishes the conditions that characterize women throughout the life course. De Beauvoirs account identifies several negative features in womens transition from maturity to old age. First, the aging of women, in contrast to the aging of men, is discontinuous. In womens life course there is rupture that corresponds to changes in her reproductive cycle (that is, menopause). Mens continuous life course is presented by de Beauvoir as the positive side of the dualism of continuous/discontinuous In the attempt to reject such images, de Beauvoir claims that there is a consequent refusal by women to accept their own aging and the designation of old.