First published 1995 by Westview Press

Published 2019 by Routledge

52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright 1995 by Cornell University Medical College

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

The Metropolitan Academic Medical Center : its role in an era of tight

money and changing expectations / edited by David E. Rogers and Eli

Ginzberg.

p. cm.

This is the Ninth Cornell University Medical College Conference on

Health Policy.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

1. Health care reformUnited States.2. Academic medical

centersUnited States.I. Rogers, David E. (David Elliott), 1926-.

II. Ginzberg, Eli, 1911-.III. Cornell University Medical

College Conference on Health Policy (9th)

RA395.A3M468 1995

362.110973dc20

94-43239

CIP

ISBN 13: 978-0-367-29382-6 (hbk)

David E. Rogers

This year, our focus on urban academic health centers represented our ninth conference on health policy. Although we started planning it over a year ago, its timing was exquisite. The concerns about how those academic medical centers (AMCs) located in urban areas should or will conduct themselvesindeed, whether they could survive in an era of tight money, changing expectations, and looming health care reformwas very much on the minds of many. The papers were provocative, and some fine intellects focused intensely on that question over a two-day period.

Though we did not settle the deceptively simple questions posed, the discussion provided new insights into how these remarkable institutions can preserve what is precious about them as they adapt to some very different times.

This subjectthe fate of medical academehas long concerned me. During my fifteen years at the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation, my colleagues and I looked intensely at the mission, the health, and the trajectory of AMCs. Fifteen years ago I published a paper with Dr. Robert Blendon entitled, The Academic Medical Center: A Stressed Institution. In that paper we concluded that we seemed to be witnessing a progressive dissolution of what had been an unusually productive symbiotic partnership between government and medical academe. That symbiosis had allowed AMCs to become the worlds largest and most sophisticated biomedical research enterprises, as well as major referral centers for the provision of complex tertiary hospital care. They were also a critical source of care for the urban poor. They trained all of the U.S. physicians and many of the other health professionals needed to care for the sick and did research and developed the technology required for a better future.

But even then there were indications that this wonderful relationship had begun to go awry. It was increasingly the view within government circles and the broader community that AMCs, once believed to be the solution to the nations health problems, had become a big part of the problem. Certain dilemmas apparent even then were threatening their future.

First was the problem posed by their unique contact with the public. Not only were the AMCs the educators of all physicians trained in the United States and the generators of most of the new biomedical knowledge, they also carried disproportionate responsibilities for providing medical care to the poor and the uninsured. In 1978 teaching hospitals connected to AMCs had only about 6 percent of the acute care beds, yet they provided almost 50 percent of the free care. This situation remains virtually unchanged today.

Second, and now very much on everyones minds, were the problems posed by their locations. More than one-quarter of the 126 AMCs are located in inner cities, where they face some of the most wrenching social and transmedical agonies of our day. Problems posed by their size and by the uncontrolled drift toward subspecialties and away from general medicine, were even then becoming worrisome.

Last, AMCs faced some serious problems, not of their own making, created by the consistent failure of government and private medicine to fix responsibilities for the equitable delivery of medical care. These problems remain. But even then this failure had led to governmental pressure on AMCs alone, rather than on medicine as a whole, to get the health care job done.

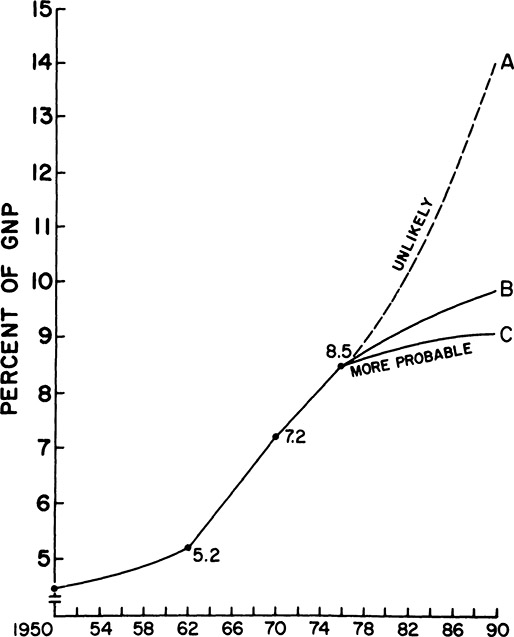

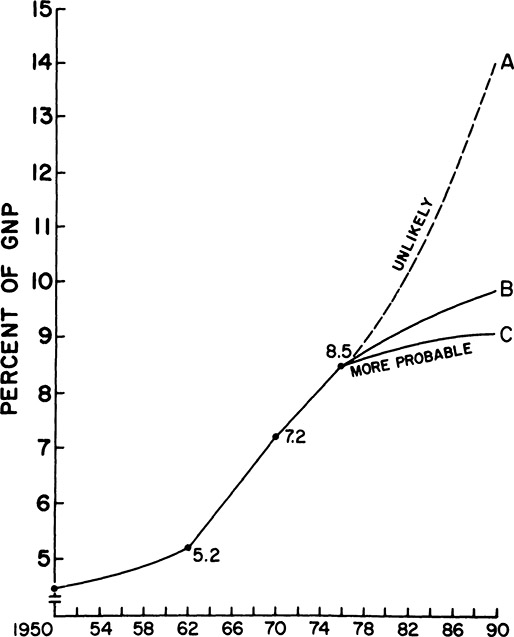

That statement shows my track record as an economic futurologist; we plowed ahead almost exactly along line A. But I was more accurate in forecasting what might happen if medical schools failed to plan carefully to be more responsive to an increasingly troubled public and tried simply to continue business as usual. If this happened, I suggested, the following scenario would ensue:

- Major teaching hospitals would begin to desert the academic ship. The pressures for cost containment would cause them to make every effort to divest themselves of medical school activities such as ongoing support of research or ambulatory care programs for the poor.

The Health Sector Growth Curve: National Health Expenditures as Percent of GNP, 19501990

- 2. There would be a steady erosion in the gains we were then making in training more generalist physicians.

- 3. The pressure for revenues would force academic medical institutions to increase the amount of private practice assumed by their faculty, and they would do so by developing increasingly specialized faculty members who would use large amounts of high-cost technology and draw high-paying patients. As a result, faculty primarily involved in clinical research or in the delivery of more generalist forms of care would have a progressively more difficult time maintaining their positions in academe.

- 4. Last, the pressures of practice would allow faculty less time for teaching medical students, and the tensions between those who generated income and those who were involved in less time-dependent, hence less reimbursable, academic pursuits would steadily escalate.

Alas, all of those things have happened. Despite increasing evidence of public and government disenchantment with the directions AMCs were taking and the kinds of health professionals we were producing, we marched resolutely onward. But now change is in the air. Every AMC is now looking anxiously inward to decide how it might best position itself to fit into a very different scheme of things.