Poor Peoples Energy Briefing 3

The EnergyWaterFood Nexus at Decentralized Scales

Synergies, trade-offs, and how to manage them

Lucy Stevens and Mary Gallagher, Practical Action, UK

This paper uses Practical Actions experiences with micro-hydro schemes to connect global nexus debates to the experiences of and solutions for remote off-grid communities and smallholder farmers. Through examples in Peru, Nepal, and Zimbabwe we exemplify the need for an integrated approach to energy, water, and food security. We show that decentralized energy provision has a huge potential to deliver the services that communities need and have a right to, while balancing the constraints of an increasingly resource-scarce environment.

Contents

A notable feature of almost all the discussions surrounding the energywaterfood nexus to date is that they have focused on national or supra-national scales. Most key background documents lack discussion of smaller, more localized scales. This is despite the fact that the majority of the food in developing countries is provided locally by smallholder farmers (IFAD and UNEP, 2013), fishers or herders; and the International Energy Agencys calculation that 55 per cent of all new electricity supply will need to be from decentralized systems if we are to reach the goal of universal energy access by 2030 (IEA, 2010).

This paper uses Practical Actions experiences with micro-hydro schemes to illustrate some of the nexus conflicts and synergies that arise for remote communities and smallholder farmers. We recognize that electricity provision through micro-hydro schemes is not the only example of nexus issues connecting water, energy, and food for poor communities. However, using examples from Peru, Nepal, and Zimbabwe we exemplify the potential added value of an integrated approach to energy, water, and food security.

Taking a Total Energy Access perspective, we demonstrate the huge potential for decentralized energy provision to deliver for poverty reduction. However, opportunities can be missed and inequalities arise where energy provision is not linked with mainstream agricultural practices. Stand-alone energy schemes have reasonably good levels of sustainability, but they may perform below their optimum and fail to account for the full needs of the community without sufficient focus on nexus issues which are well understood by communities themselves as well as ensuring that the right kinds of institutions are in place to handle trade-offs as they arise.

Opportunities can be missed where energy provision is not linked with mainstream agricultural practices

Nexus debates are still relatively new; the practical lessons of adopting a nexus approach still need to be explored. There is an urgent need for capacity building at different levels within both donors and governments to bring better cross-sectoral working and a greater focus on decentralized scales and the needs of smallholder farmers. A focus on productive uses should not over-emphasize off-farm enterprises, but build on what people are already doing. Initiatives such as the SE4ALL High Impact Opportunity on nexus issues which brings key players in the sector together must support this drive, and ensure that the emphasis lies not only on large-scale national and supra-national issues, but also on the needs of poor people.

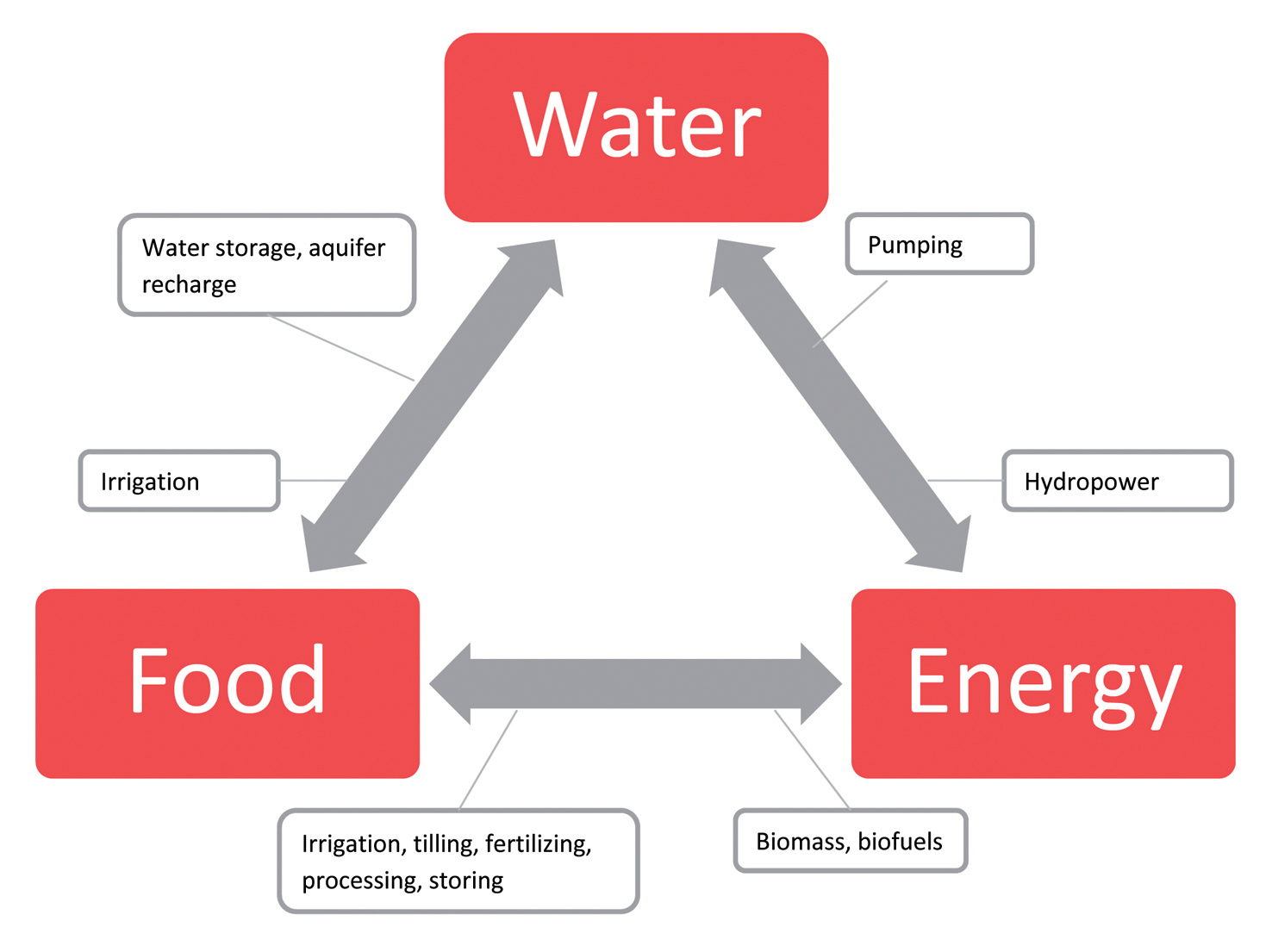

We live in a world of growing resource scarcity. Demands on water, food, and energy in particular will only increase as populations rise. It is now widely recognized that these resources are deeply interlinked. If we are to respond to the challenge in any one of these areas we must consider each resource as part of an interconnected system an approach now commonly referred to as nexus thinking. Some of the connections are illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1 Connections between water, energy, and food

This nexus is complex. The competing uses of water, energy, and food can be controversial; in the energy sector, modern fossil fuel energy consumption is directly linked to climate change, and the replacement of traditional food crops with fuel on a large scale is a challenging option when fertile land is increasingly sought after and food security is at risk.

Nexus thinking is also not a wholly new approach. For Practical Action, making the connections between different elements of the nexus relates to our Total Energy Access approach (Practical Action, 2014). This highlights how poor people need access to a range of energy supplies and services in households, productive uses, and community services to support human, social, and economic development. Smallholder farmers are acutely aware of the importance of an integrated approach at home and in the fields. They use various resources to ensure food security every day. Animal waste for example can provide a free, sustainable source of power all year round in the form of biogas, and biomass is a useful form of fertilizer to grow healthy crops.

Making the connections between different elements of the nexus relates to Total Energy Access

We have many decades of experience of bottom-up, community-based planning to design energy systems with and for poor people whose needs, due to location, weak institutions or lack of political or economic influence are not normally factored into national energy plans. In this paper we consider what relevance current literature and the global debate have to a poor persons experience of energy access and resource scarcity.

We draw on our practical experience of micro-hydro systems in Nepal, Peru, and Zimbabwe. This is not because micro-hydro is the only appropriate option to meet resource challenges, or the only example of the nexus at these scales, but because our experience of competing demands on water and energy for household and productive uses offers us some useful lessons about the benefits and trade-offs that arise.

In some cases, nexus thinking was not an explicit goal at the start of a project. Where this is the case we retrospectively apply a nexus lens to see the extent to which trade-offs were present and the potential for synergies missed. Finally we analyse some of Practical Actions current work in Zimbabwe which makes a more deliberate attempt to tackle nexus issues. We review the potential of these schemes to maximize benefits from the energy infrastructure in terms of increased incomes and improved resilience.

In recent years, the importance of the connections (or nexus) between the key resources of water, energy, and food has been increasingly recognized. The concept gained momentum at events such as the German government-sponsored 2011 conference in Bonn titled The Water, Energy and Food Security Nexus Solutions for the Green Economy and the resulting web platform it launched. It has been further promoted by international agencies, donors, governments, and NGOs in the name of achieving sustainable development. It has been adopted by technical experts in these fields and the private sector, especially multinationals searching for ways to ensure resource security within value chains. There are also examples of different stakeholders coming together to discuss shared risks, such as the report published by WWF and the brewers Saab Miller on