THE BREATHLESS ZOO

Nigel Rothfels and Garry Marvin

GENERAL EDITORS

ADVISORY BOARD:

Steve Baker

University of Central Lancashire

Susan McHugh

University of New England

Jules Pretty

University of Essex

Alan Rauch

University of North Carolina at Charlotte

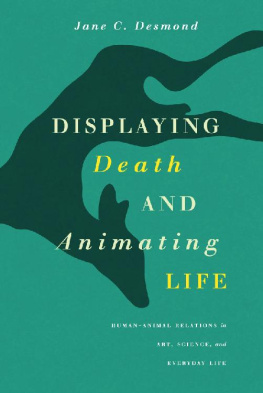

Books in the Animalibus series share a fascination with the status and the role of animals in human life. Crossing the humanities and the social sciences to include work in history, anthropology, social and cultural geography, environmental studies, and literary and art criticism, these books ask what thinking about nonhuman animals can teach us about human cultures, about what it means to be human, and about how that meaning might shift across times and places.

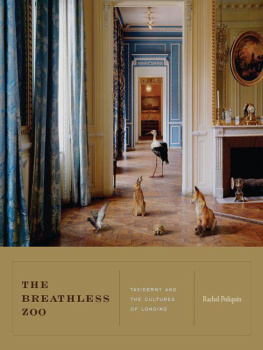

THE BREATHLESS ZOO | TAXIDERMY AND THE CULTURES OF LONGING | Rachel Poliquin |

THE PENNSYLVANIA

STATE UNIVERSITY

PRESS

UNIVERSITY PARK,

PENNSYLVANIA

Library of Congress

Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Poliquin, Rachel, 1975

The breathless zoo : taxidermy and the cultures of longing / Rachel Poliquin.

p. cm. (Animalibus : of animals and cultures)

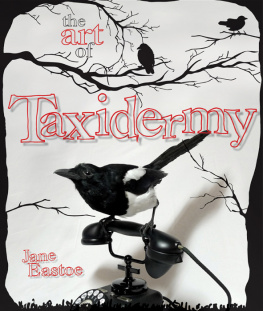

Summary: A cultural and poetic analysis of the art and science of taxidermy, from sixteenth-century cabinets of wonders to contemporary animal artProvided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-271-05372-1

(cloth : acid-free paper)

1. TaxidermyHistory.

2. TaxidermySocial aspects.

3. TaxidermyPsychological aspects.

4. Human-animal relationships.

5. DesireSocial aspects.

6. Animals in art.

7. Animals in literature.

I. Title.

QL 63. P 65 2012

590.752dc23

2011045700

Copyright 2012

The Pennsylvania State University

All rights reserved

Printed in Singapore by

Tien Wah Press, Ltd.

Published by

The Pennsylvania State University Press, University Park, PA 16802-1003

The Pennsylvania State University Press is a member of the Association of American University Presses.

It is the policy of The Pennsylvania State University Press to use acid-free paper. Publications on uncoated stock satisfy the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Material, ANSI Z 39.481992.

Designed by Regina Starace

CONTENTS

ILLUSTRATIONS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This project would not have been possible without a postdoctoral fellowship from the Social Sciences and Research Council of Canada. I would like to thank Harriet Ritvo and the History Department of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology for hosting me, however briefly. A special thank you to all the librarians and archivists who helped this project along, particularly James Hatton at the Natural History Museum in London, Sarah Kenyon and Claire Pike at the Saffron Walden Museum, Nina Cummings and Armand Esai at the Field Museum, and Dana Fisher at the Ernst Mayr Library at Harvard Universitys Museum of Comparative Zoology. For their encouragement, support, and assistance, I would also like to thank Nigel Rothfels, Garry Marvin, Kendra Boileau, Steve Plant, Lisa Grekul, Eva-Marie Krller, and, of course, my family, Tobias, Duane, Judy, Morgan, Erin, and Beatrice.

INTRODUCTION

In 2004, Nanoq: Flat Out and Bluesome opened in Spike Island, a large, white-walled art space in Bristol, England. On display were ten taxidermied polar bears, each isolated in its own custom glass case, all transported from separate locations across Great Britain to exist briefly together yet solitary. The exhibition marked the conclusion of Brynds Snbjrnsdttir and Mark Wilsons quest to find and photograph every mounted polar bear in the United Kingdom, a three-year journey that unearthed thirty-four bears. Most were located in natural history museums, some on display, some in storage, boxed in among filing cabinets and other discarded displays. Other bears stood in parlors and hallways of private homes or blended with the eclectic dcor of a country pub.

Each of the bears was photographed in situ where Snbjrnsdttir and Wilson discovered them, captured in the mix and muddle of their dwellings, not their native environment, to be sure, but their second and more permanent home. Although the photographs exude a colorful vitality, there is also an indeterminate wistfulness to the images, a sense of lingering or waiting: the gentle sadness of the bears stoic persistence in the face of artificial ice floes, bottles of beer, and African animals. One of the bears holds a wicker basket of glowing plastic flowers (); another is penned in between a wallaby and a tiger; yet another has been forgotten behind a dust-covered bicycle and a childs rocking horse. The compromising situations envelop the bears in a vague sense of noble tragedy, an aura captured by the projects ambiguously melancholic title: Nanoq: Flat Out and Bluesome, nanoq being the Inuit name for polar bear. Flat out implies death, fast forward, and flatten like stretched skins, while bluesome suggests both the bluish light of Arctic snow and the weight of melancholia.

The wistfulness of the photographs and exhibition title was sharpened by the display of the ten bears themselves. The atmosphere of the gallery was marked by a sense of absence, an uneasy silence, a loneliness and longing. Perhaps it was the austerity of the space, with its white walls, white floor, glass, clean white metal, and isolated honey-white bears. Or perhaps the sheer physical presence of the bears captured and communicated something that two-dimensional photographic images never could.

As part of their project, the artists researched the personal history of each specimen. The bears were variously shot during Arctic adventures or euthanized in zoos. One died of old age; another traveled with a circus. But whatever their precise story and route, polar bears are aliens to Great Britain; they were all taken from their native landscapes at some stage of life or death and manhandled into everlasting postures. The artists choice to document specimens of an Arctic species, rather than creatures indigenous to Britain, adds an additional layer of significance to the polar bears. These are not common indigenous creatures. They are not unwanted invasive species but coveted imports, and as such are necessarily endowed with longing. Without the desire to capture, to kill, to see, to document, these bears would not be in Britain and certainly would not have been taxidermied.

Many of the bears date to the mid-nineteenth century and linger as relics of And with this early history, the bears also evince the Victorian infatuation with taxidermy itself. Some of the bears were preserved by the greats of late Victorian taxidermy, most notably Rowland Ward and Edward Gerrard & Sons. The bears aggressive standing poses make clear the eras reveries of exotic animal dangers in distant lands. As such, the bears are documents of a British cultural imaginary which has slippedthankfully or notforever into history.

More pressingly, from a contemporary perspective, the bears can also be read as an anxious narrative of global warming. Here are so many bears from territories under threat. But if the bears are troubling environmental documents, they also stand as quiet educators. They offer visitors an opportunity to experience the majestic size of polar bears and to appreciate personally, intimately, the dignity and exceptionality of the species. If the bears provide a critique of past collecting practices, they also make material the intrinsic worth of preserving animals. If a creature becomes extinct, no matter how much video footage and photographic images may have been amassed, nothing can ever compare to the physical presence of the animal, admittedly dead and stuffed, but a physical presence nonetheless. The taxidermied remains of passenger pigeons, quaggas, great auks, and all other extinct species are precious beyond words. They are the definition of irreplaceable.

Next page