THE PENGUIN PRESS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street,

New York, New York 10014, U.S.A.

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.) Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England Penguin Ireland, 25 St. Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland (a division of Penguin Books Ltd) Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd) Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, Auckland 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd) Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank, Johannesburg 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices:

80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL, England

First published in 2012 by The Penguin Press,

a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc.

Copyright Nate Silver, 2012

All rights reserved

Illustration credits

Figure 4-2: Courtesy of Dr. Tim Parker, University of Oxford

Figure 7-1: From 1918 Influenza: The Mother of All Pandemics by Jeffery Taubenberger and David Morens, Emerging Infectious Disease Journal, vol. 12, no. 1, January 2006, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Figures 9-2, 9-3A, 9-3C, 9-4, 9-5, 9-6 and 9-7: By Cburnett, Wikimedia Commons

Figure 12-2: Courtesy of Dr. J. Scott Armstrong, The Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING IN PUBLICATION DATA

Silver, Nate.

The signal and the noise : why most predictions fail but some dont / Nate Silver.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-101-59595-4

1. Forecasting. 2. ForecastingMethodology. 3. ForecastingHistory. 4. Bayesian statistical decision theory. 5. Knowledge, Theory of. I. Title.

CB158.S54 2012

519.5'42dc23 2012027308

While the author has made every effort to provide accurate telephone numbers, Internet addresses, and other contact information at the time of publication, neither the publisher nor the author assumes any responsibility for errors, or for changes that occur after publication. Further, publisher does not have any control over and does not assume any responsibility for author or third-party Web sites or their content.

No part of this book may be reproduced, scanned, or distributed in any printed or electronic form without permission. Please do not participate in or encourage piracy of copyrighted materials in violation of the authors rights. Purchase only authorized editions.

To Mom and Dad

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

T his is a book about information, technology, and scientific progress. This is a book about competition, free markets, and the evolution of ideas. This is a book about the things that make us smarter than any computer, and a book about human error. This is a book about how we learn, one step at a time, to come to knowledge of the objective world, and why we sometimes take a step back.

This is a book about prediction, which sits at the intersection of all these things. It is a study of why some predictions succeed and why some fail. My hope is that we might gain a little more insight into planning our futures and become a little less likely to repeat our mistakes.

More Information, More Problems

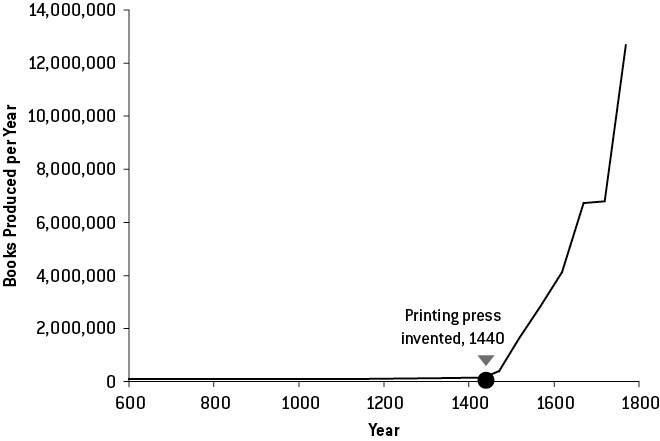

The original revolution in information technology came not with the microchip, but with the printing press. Johannes Gutenbergs invention in 1440 made information available to the masses, and the explosion of ideas it produced had unintended consequences and unpredictable effects. It was a spark for the Industrial Revolution in 1775, a tipping point in which civilization suddenly went from having made almost no scientific or economic progress for most of its existence to the exponential rates of growth and change that are familiar to us today. It set in motion the events that would produce the European Enlightenment and the founding of the American Republic.

But the printing press would first produce something else: hundreds of years of holy war. As mankind came to believe it could predict its fate and choose its destiny, the bloodiest epoch in human history followed.

Books had existed prior to Gutenberg, but they were not widely written and they were not widely read. Instead, they were luxury items for the nobility, produced one copy at a time by scribes. so a book like the one youre reading now would cost around $20,000. It would probably also come with a litany of transcription errors, since it would be a copy of a copy of a copy, the mistakes having multiplied and mutated through each generation.

This made the accumulation of knowledge extremely difficult. It required heroic effort to prevent the volume of recorded knowledge from actually decreasing, since the books might decay faster than they could be reproduced. Various editions of the Bible survived, along with a small number of canonical texts, like from Plato and Aristotle. But an untold amount of wisdom was lost to the ages, and there was little incentive to record more of it to the page.

The pursuit of knowledge seemed inherently futile, if not altogether vain. If today we feel a sense of impermanence because things are changing so rapidly, impermanence was a far more literal concern for the generations before us. There was nothing new under the sun, as the beautiful Bible verses in Ecclesiastes put itnot so much because everything had been discovered but because everything would be forgotten.

The printing press changed that, and did so permanently and profoundly. Almost overnight, the cost of producing a book decreased by about three hundred times, The store of human knowledge had begun to accumulate, and rapidly.

FIGURE I-1: EUROPEAN BOOK PRODUCTION

As was the case during the early days of the World Wide Web, however, the quality of the information was highly varied. While the printing press paid almost immediate dividends in the production of higher quality maps, Paradoxically, the result of having so much more shared knowledge was increasing isolation along national and religious lines. The instinctual shortcut that we take when we have too much information is to engage with it selectively, picking out the parts we like and ignoring the remainder, making allies with those who have made the same choices and enemies of the rest.

The most enthusiastic early customers of the printing press were those who used it to evangelize. Martin Luthers Ninety-five Theses were not that radical; similar sentiments had been debated many times over. What was revolutionary, as Elizabeth Eisenstein writes, is that Luthers theses did not stay tacked to the church door.a runaway hit even by modern standards.

The schism that Luthers Protestant Reformation produced soon plunged Europe into war. From 1524 to 1648, there was the German Peasants War, the Schmalkaldic War, the Eighty Years War, the Thirty Years War, the French Wars of Religion, the Irish Confederate Wars, the Scottish Civil War, and the English Civil Warmany of them raging simultaneously. This is not to neglect the Spanish Inquisition, which began in 1480, or the War of the Holy League from 1508 to 1516, although those had less to do with the spread of Protestantism. The Thirty Years War alone killed one-third of Germanys population,