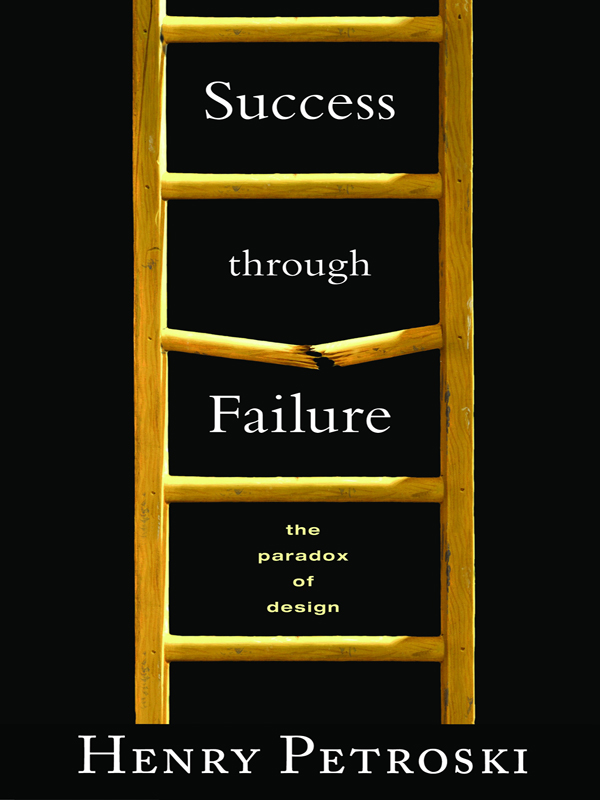

SUCCESS THROUGH FAILURE

OTHER BOOKS BY HENRY PETROSKI

Pushing the Limits: New Adventures in Engineering

Small Things Considered: Why There Is No Perfect Design

Paperboy: Confessions of a Future Engineer

The Book on the Bookshelf

Remaking the World: Adventures in Engineering

Invention by Design: How Engineers Get from Thought to Thing

Engineers of Dreams: Great Bridge Builders

and the Spanning of America

Design Paradigms: Case Histories of Error and Judgment

in Engineering

The Evolution of Useful Things

The Pencil: A History of Design and Circumstance

Beyond Engineering: Essays and Other Attempts to Figure

without Equations

To Engineer Is Human: The Role of Failure in Successful Design

SUCCESS THROUGH FAILURE

The Paradox of Design

Henry Petroski

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS  Princeton and Oxford

Princeton and Oxford

Copyright 2006 by Henry Petroski

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent

to Permissions, Princeton University Press

Published by Princeton University Press, 41 William Street,

Princeton, New Jersey 08540

In the United Kingdom: Princeton University Press, 3 Market Place,

Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1SY

All Rights Reserved

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Petroski, Henry.

Success through failure : the paradox of design / Henry Petroski.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN-13: 978-0-691-12225-0 ((hardcover) : alk. paper)

ISBN-10: 0-691-12225-3 ((hardcover) : alk. paper)

1. Engineering designCase studies. 2. System failures

(Engineering)Case studies. I. Title.

TA174.P4739 2006

620.0042dc22 2005034126

Small portions of this material appeared first in American Scientist,

Harvard Business Review, and the Washington Post Book World

This book has been composed in Adobe Caslon and Helvetica Neue

Printed on acid-free paper.

pup.princeton.edu

Printed in the United States of America

1 3 5 7 9 10 8 6 4 2

To Karen

CONTENTS

PREFACE

This book was written in conjunction with my preparation of a sequence of three public lectures on the topic of engineering and design to be delivered at Princeton University. The text incorporates the subject of those Louis Clark Vanuxem Lectures, given in Princeton on December 7, 8, and 9, 2004, but is in no way a manuscript of the talks, whose titles were:

1. From Platos Cave to PowerPoint: An Illustrated Lecture on the Illustrated Lecture

2. Good, Better, Better: The Evolution of Imperfect Things

3. The Historical Future: The Persistence of Failure

The written format has allowed me to expand the range of things and systems covered and to include more examples and detail than did the spoken word. Unfortunately, space in a book does not allow nearly as many illustrations as were used in my PowerPoint presentations at Princeton.

Engineers approach the lecture format in quite a different manner from that of humanists. In my experience, the latter typically read verbatim from a prepared text and use few, if any, graphics or illustrations. In contrast, engineers tend to use a good number of slides and related visual aidsin the form of drawings, diagrams, charts, graphs, equations, and demonstrationsto illustrate their talks, which are typically delivered extemporaneously. That is not to say that they are unprepared, for the engineer will more likely than not have gone over and over the visual materials and the essence of the commentary that will accompany them. The number and order of slides will be edited and reedited in the weeks leading up to the talk, for which the illustrations serve also much the same purpose as do prompting notes on index cards. Over the years, mechanical, visual, and digital devices ranging from magic lanterns to computer software like PowerPoint have greatly facilitated the process of preparing and projecting slides. Still, there remains room for improvement, as is described in the first chapter of this book.

Writing also benefits greatly from the use of computers, of course, but no author should ever blame malfunctioning electrons for the misfire of neurons in his own brain. If I have made any errors in this book, they are my responsibility alone and not that of the individuals who have helped me in so many ways. As always, I am deeply indebted to libraries and librarians, most importantly those at Duke University, and in particular Eric Smith and Linda Martinez. I am especially grateful to them for their assistance in helping me identify and secure obscure sources from incomplete references, and for introducing me to increasingly powerful electronic databases. And I am once again greatly in debt to the largely anonymous but immensely generous institution of Interlibrary Loan.

I am also grateful to Jack Judson, director of the Magic Lantern Castle Museum in San Antonio, Texas, who guided me through his outstanding collection of lanterns and related materials; to Tom Hope, who provided me hard historical data on the development of the slide projector; to Robin Young, who invited me and my wife to visit Stonecrop Gardens and who ensured that we had a good view of its flint bridge; and to Pete Lewis, who provided insight into and documentation for cast-iron bridges. Charles Siple, an inveterate correspondent and draftsman, was kind enough to draw the diagrams of splitting wedges and an arch from my amateur sketches. As usual, my family was also extremely helpful. Stephen Petroski helped me find documentation for my statements about design in sports, and Karen Petroski improved my knowledge of the Internet. Once again, Catherine Petroski was my first reader, and she also served as photographer and provider of digital images and graphics.

I was asked to write this book by Sam Elworthy of Princeton University Press. I am grateful to him for his persistence in convincing me to present the series of lectures and to prepare a book on the topic of design. The Princeton University Committee on Public Lectures and its chair, Sergio Verd, extended to me the invitation to speak in the Vanuxem lecture series, which dates from 1912. It is an honor for me to join the distinguished list of Vanuxem lecturers.

Finally, I appreciate the planning, warm reception, and hospitality that members of the Princeton community extended to Catherine and me over the three days of the lectures. Susan Jennings and an excellent audiovisual crew made sure that the mechanical and electronic details were in order in the lecture room in McCosh Hall. David Billington, who was enormously generous with his time, turned me loose in his Maillart Archive and allowed me to sit in on some of his own lectures and to meet with his students. David and Phyllis Billington were most gracious hosts, who helped Catherine and me experience Princeton in times of leisure and in time of emergency.

SUCCESS THROUGH FAILURE

INTRODUCTION

Desire, not necessity, is the mother of invention. New things and the ideas for things come from our dissatisfaction with what there is and from the want of a satisfactory thing for doing what we want done. More precisely, the development of new artifacts and new technologies follows from the failure of existing ones to perform as promised or as well as can be hoped for or imagined. Frustration and disappointment associated with the use of a tool or the performance of a system puts a challenge on the table: Improve the thing. Sometimes, as when a part breaks in two, the focal point for the improvement is obvious. Other times, such as when a complex system runs disappointingly slowly, the way to speed it up may be far from clear. In all cases, however, the beginnings of a solution lay in isolating the cause of the failure and in focusing on how to avoid, obviate, remove, or circumvent it. Inventors, engineers, designers, and common users take up such problems all the time.

Next page

Princeton and Oxford

Princeton and Oxford