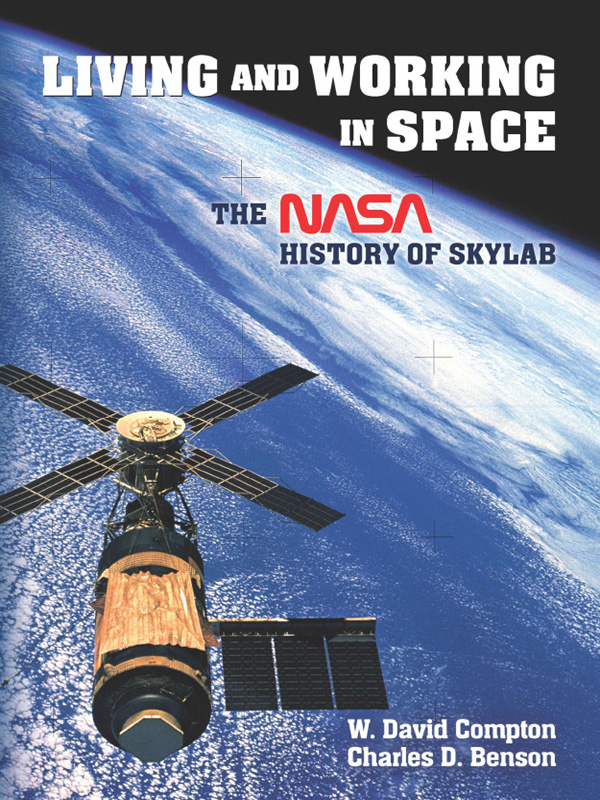

LIVING AND WORKING

IN SPACE

A NASA HISTORY OF SKYLAB

W. David Compton

Charles D. Benson

Introduction to the Dover Edition by

Paul Dickson

Dover Publications, Inc.

Mineola, New York

NASA maintains an internal history program for two principal reasons. (1) Publication of official histories is one way in which NASA responds to the provision of the National Aeronautics and Space Act of 1958 that requires NASA to provide for the widest practicable and appropriate dissemination of information concerning its activities and the results thereof. (2) Thoughtful study of NASA history can help managers accomplish the missions assigned to the agency. Understanding NASAs past aids in understanding its present situation and illuminates possible future directions.

One advantage of working on contemporary history is access to participants. During the research phase, the authors conducted numerous interviews. Subsequently they submitted parts of the manuscript to persons who had participated in or closely observed the events described. Readers were asked to point out errors of fact and questionable interpretations and to provide supporting evidence. The authors then made such changes as they believed justified. The opinions and conclusions set forth in this book are those of the authors; no official of the agency necessarily endorses those opinions or conclusions.

Copyright

Introduction copyright 2011 by Paul Dickson

All rights reserved.

Bibliographical Note

This Dover edition, first published in 2011, is a slightly altered republication of the work originally published in NASA History Series (NASA SP4208), Washington D.C., in 1983. The color photos originally on pages 355360 are now in black and white within the book, and have been reproduced in color on the inside covers. The color artwork and information originally on the inside covers has been moved to page xiv and has been reproduced in black and white. A new Introduction by Paul Dickson has been added to this edition.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Compton, William David, 1927

Living and working in space: a NASA history of skylab / W. David Compton, Charles D. Benson. Dover ed. / introduction to the Dover edition by Paul Dickson.

p. cm.

Originally published: Washington, D.C.: Scientific and Technical Information Branch, National Aeronautics and Space Administration: For sale by the Supt. of Docs., U.S. G.P.O., 1983; in series: NASA History Series; and NASA SP; 4208. With new introd.

Summary: The official record of Americas first space station, this book from the NASA History Series chronicles the Skylab program from its planning during the 1960s through its 1973 launch and its conclusion in 1979. It presents definitive accounts of the projects goals and achievements as well as its use of discoveries and technology developed during the Apollo program. 1983 edition Provided by publisher.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 13: 978-0-486-48218-7 (pbk.)

ISBN 10: 0-486-48218-9 (pbk.)

1. Skylab Program. I. Benson, Charles D. II. Title.

TL789.8.U6S5546 2011

629.44'2dc22

2011006734

Manufactured in the United States by Courier Corporation

48218901

www.doverpublications.com

Mention the word Skylab to people of a certain age and their eyes will most likely look skyward for a fraction of a second. This is because during the spring and early summer of 1979 the abandoned U.S. space station was drifting from its decaying orbit and was heading back to earth. The cry went up: Skylab is falling! Skylab is falling!

On March 28, the Three Mile Island nuclear reactor near Harrisburg, Pennsylvania had a partial melt down. Coming two weeks after the release of the nuclear disaster film, The China Syndrome, the dream of nuclear power as a peaceful, environmentally sound option was over. Then Skylab crowded Three Mile Island out of the headlines. People were initially afraid there would be death and destruction. Technology suddenly seemed demonic.

On July 11, over six years after it went into orbit, Skylab fell to earth, breaking up in the atmosphere and scattering its remains across the Indian Ocean and the Australian outback. While there was no damage to life or property, there was more than a little damage to NASAs reputation, which in its post-lunar landing phase was, as Time magazine later put it, starting to look as adrift as Skylab itself. Nine days after the fall of Skylab the world celebrated the tenth anniversary of the Apollo 11 moon landing, suggesting backward rather than forward movement.

If there was anyone rejoicing, it was a seventeen-year-old beer truck driver who found some charred Skylab fragments in his backyard. He bagged them up, grabbed the next flight to California, and claimed the $10,000 prize, which a San Francisco newspaper had offered to the first person to bring a piece of Skylab to its office.

To this day there are many whose only recollection of Skylab was the fiery return of the largest machine man had put into space. This is unfortunate because the real story of Skylab is more complicated, heroic, and successful than that.

For starters, Americas first space station was something of a makeshift thing. It was retrofitted from the enormous, nine-story tall, third stage of a Saturn V booster, which would no longer be needed to send men to the moon after the cancellation of the Apollo program. Skylab also picked up practical technology developed by the Air Force, which had decided in 1963 to develop a program to send crews into orbiting space stations called Manned Orbiting Laboratories (MOL). The purpose of these stations was primarily for military reconnaissance. But over the years that the MOL was being developed, unmanned satellites became more efficient eyes in the sky, and the need for them diminished and finally disappeared. When the MOL project was cancelled in 1969, NASA picked up various contracts from the Air Force for Skylab including one for the technology to feed a crew in the weightlessness of a space station.

The unmanned Skylab was fired into orbit on May 14, 1973. It immediately developed technical problems, the most significant of which occurred during the launch. The flow of air caused a meteoroid shield to come off, tearing off one of two solar panels and preventing the other from deploying in the process. The damage resulted in reduced power for the station. The first crew, Pete Conrad, Paul Weitz, and Joe Kerwin arrived eleven days later in an Apollo Command and Service Module and their first task was to repair the damage. Once repairs were complete, full power was restored. That crew spent twenty-eight days in orbit. The second crew, Alan Bean, Jack Lousma, and Owen Garriot spent fifty-nine days in space, but only after overcoming their own problems and some very tense moments. First, a thruster leak caused rendezvous with the station to be more challenging than expected, and then, once the crew was on board, a second thruster developed a leak. Plans were drawn up for a rescue but the crew was able to make adjustments and complete the mission as planned. The final Skylab crew, Jerry Carr, Bill Pogue, and Edward Gibson spent eighty-four days in space.

Each Skylab crew set new spaceflight duration records. The record set by the final crew was not broken by an American astronaut until the Shuttle-Mir program more than twenty years later. Skylab was decommissioned in February 1974 and the $2.5 billion habitat was now debris. It was thought that if nothing was done, according to early estimates, gravity would return it to earth in 1983. The hope was that a shuttle, then in the planning stages would be sufficiently developed so that before the fall a booster could be attached to Skylab to send it to a higher, more permanent orbit. But sun spot activity changed the dynamics of the orbit. The estimate was lowered and the shuttle wasnt ready. The rest is history.