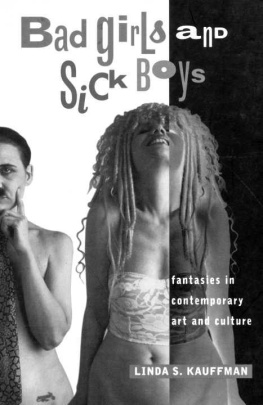

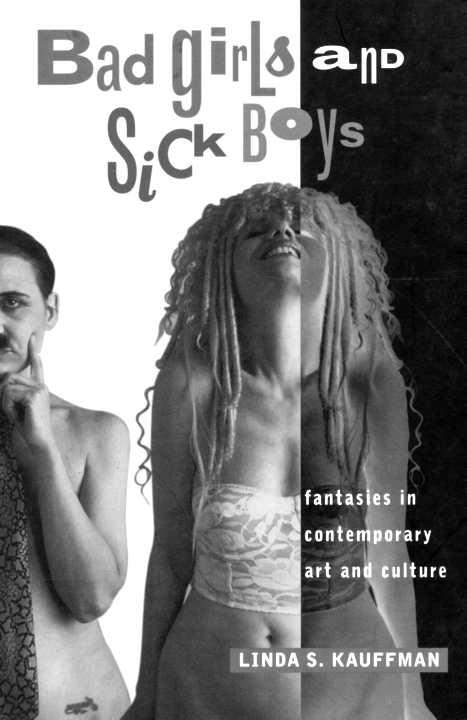

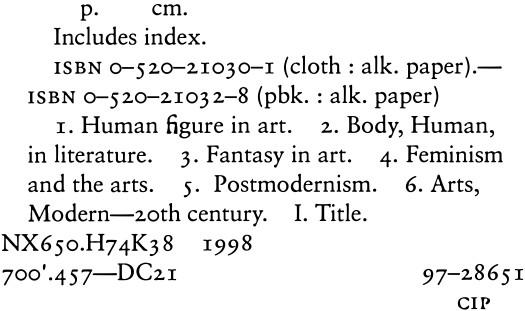

Linda S. Kauffman

For Ira Mehiman and in memory of Bob Flanagan (December 26, 1952-January 4, 1996)

ix

xi

i

When I began research on this book in Berkeley in 1991, 1 could never have imagined the odyssey that lay ahead. I did not even know what I was looking for, but what I found were generous friends all over the United States and Europe. In the San Francisco Bay area, lain Boal, Terry Castle, Carol Clover, and Jeff Escoffier helped give shape to early bad drafts and sickly prose. Jim Brook introduced me to J. G. Ballard's work; Rita Cummings Belle became my scout in cyberspace. I'm grateful for a fellowship in i991-92. at the Humanities Institute at the University of California, Davis, particularly for the comradeship of Kay Flavell and Laura Mulvey.

In 1993, the University of California Humanities Research Institute at U.C. Irvine invited me to participate in the faculty seminar "Minority Discourse." I thank Mark Rose, U.C.H.R.I. director, and Valerie Smith, as well as the institute's staff, especially researcher Chris Aschan.

I owe both of these fellowships to six indefatigable referees John Bender, Deirdre David, Frank Lentricchia, Marjorie Perloff, Garrett Stewart, and Catharine Stimpson. Tanya Augsburg, Marcie Frank, Glenn Marcus, and Peggy Phelan shared ideas and research. John Arno, Anthony DeCurtis, Mark Harris, Howard Norman, Jane Shore, Alice Wexler, and David Wyatt challenged and inspired me, while providing all sorts of practical help.

For research leave, funds, and technical support, I am grateful to the English Department and staff, the College of Arts and Humanities, the Office of Graduate Studies and Research, the Office of International Affairs, and the Committee on Africa and the Americas, all of the University of Maryland, College Park. My students, particularly my intrepid researchers Jonathan Ferguson, Marsha Gordon, Reva Gupta, Katrien Jacobs, Devin Orgeron, David Paddy, Joe Schaub, Elizabeth Swayze, Deb Taylor, and Caroline Wilkins, gleefully supplied me with numerous examples of bad girls and sick boys.

My agent, Andrew Blauner, has been an unwavering supporter, faxing me a steady supply of items hot off the press. His acumen and intellect made this a better book. At the University of California Press, I thank Naomi Schneider, my editor; Rachel Berchten, Robert Irwin, and Ruth Veleta; as well as readers Gloria Frym, Lisa Lowe, and especially David Shumway for immeasurably improving the manuscript.

Finally, among the artists who so generously shared their time, J. G. Ballard, David Cronenberg, Matuschka, Orlan, Sheree Rose, and Carolee Schneemann deserve special mention. My gratitude to John and Frances Maclntyre, Kay Austen, Richard Dysart, Kathryn Jacobi, and Dr. Robert Gerard is boundless. I dedicate this book in loving memory of Bob Flanagan, who died too soon, and to Ira, who found me just in time.

September 15, 1997

Washington, D.C.

Contemporary culture is saturated not with pornography but with fantasy. The performers, filmmakers, and writers in this book are dedicated to decoding those fantasies. The bad girls in these pages are savage satirists with a keen sense of the absurd. Some of the sick boys similarly exhibit their own bodies as medical specimens; others seize medicine as material and metaphor. Collectively, the work of the women and men whom I discuss is too literal for art, too visceral for porn. These artists approach the body as material in every sense of the word: as matter-tangible and tactile-it is what matters most. The body is the materialist base, a methodological field for investigations of politics, history, identity. The body is simultaneously evidence of and material witness to the process of metamorphosis mapped here. That metamorphosis is the result of radical innovations in science, medicine, and technology, but the specialists responsible for these innovations seldom analyze their larger implications. In public policy and the news media, moreover, these developments are usually depicted in either utopian or apocalyptic terms-as if they will lead to either salvation or doom. In contrast, the artists in this book serve as interpreters of this brave new world, for by seizing these new technologies to radicalize artistic practices, they challenge society's most cherished assumptions about the body's integrity and rectitude.

We need artists to interpret the new technologies, for only they have the means to go beyond technology to analyze the underlying motivations and contradictory impulses inherent in it. Only they can expose the latent and manifest meaning of the world that already invisibly envelops us. These artists are the real translators of contemporary culture, revealing what is really happening at a moment when we are moving toward a very different understanding of what culture might be.

STRUCTURE AND METHODOLOGY

This study is divided into nine chapters, each subdivided into three parts. Part 11, "Performance for the Twenty-first Century," is devoted to performers who exhibit what is past, passing, and to come for the human body. Some explore the body's elemental origins and earliest mythologies, while others focus on a posthuman future. Posthuman signifies the impact technology has had on the human body. Any candidate for a pacemaker, prosthetics, plastic surgery, or Prozac, sex reassignment surgery, in vitro fertilization, or gene therapy, can be defined as posthuman. Our views of these developments derive wholly from what specialistsdoctors, researchers, psychiatrists-report; however, artists are beginning to intervene. In the process, they provide new insights and new metaphors, deconstructing the ideas of the museum and the human.

Next page