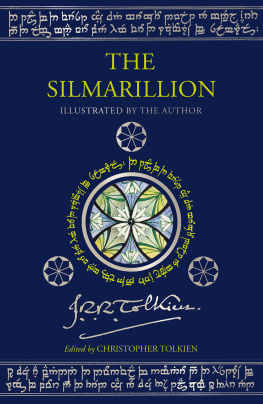

The Silmarillion, now published four years after the death of its author, is an account of the Elder Days, or the First Age of the World. In The Lord of the Rings were narrated the great events at the end of the Third Age; but the tales of The Silmarillion are legends deriving from a much deeper past, when Morgoth, the first Dark Lord, dwelt in Middle-earth, and the High Elves made war upon him for the recovery of the Silmarils.

Not only, however, does The Silmarillion relate the events of a far earlier time than those of The Lord of the Rings; it is also, in all the essentials of its conception, far the earlier work. Indeed, although it was not then called The Silmarillion, it was already in being half a century ago; and in battered notebooks extending back to 1917 can still be read the earliest versions, often hastily pencilled, of the central stories of the mythology. But it was never published (though some indication of its content could be gleaned from The Lord of the Rings), and throughout my fathers long life he never abandoned it, nor ceased even in his last years to work on it. In all that time The Silmarillion, considered simply as a large narrative structure, underwent relatively little radical change; it became long ago a fixed tradition, and background to later writings. But it was far indeed from being a fixed text, and did not remain unchanged even in certain fundamental ideas concerning the nature of the world it portrays; while the same legends came to be retold in longer and shorter forms, and in different styles. As the years passed the changes and variants, both in detail and in larger perspectives, became so complex, so pervasive, and so many-layered that a final and definitive version seemed unattainable. Moreover the old legends (old now not only in their derivation from the remote First Age, but also in terms of my fathers life) became the vehicle and depository of his profoundest reflections. In his later writing mythology and poetry sank down behind his theological and philosophical preoccupations: from which arose incompatibilities of tone.

On my fathers death it fell to me to try to bring the work into publishable form. It became clear to me that to attempt to present, within the covers of a single book, the diversity of the materials to show The Silmarillion as in truth a continuing and evolving creation extending over more than half a century would in fact lead only to confusion and the submerging of what is essential. I set myself therefore to work out a single text, selecting and arranging in such a way as seemed to me to produce the most coherent and internally self-consistent narrative. In this work the concluding chapters (from the death of Trin Turambar) introduced peculiar difficulties, in that they had remained unchanged for many years, and were in some respects in serious disharmony with more developed conceptions in other parts of the book.

A complete consistency (either within the compass of The Silmarillion itself or between The Silmarillion and other published writings of my fathers) is not to be looked for, and could only be achieved, if at all, at heavy and needless cost. Moreover, my father come to conceive The Silmarillion as a compilation, a compendious narrative, made long afterwards from sources of great diversity (poems, and annals, and oral tales) that had survived in agelong tradition; and this conception has indeed its parallel in the actual history of the book, for a great deal of earlier prose and poetry does underlie it, and it is to some extent a compendium in fact and not only in theory. To this may be ascribed the varying speed of the narrative and fullness of detail in different parts, the contrast (for example) of the precise recollections of place and motive in the legend of Trin Turambar beside the high and remote account of the end of the First Age, when Thangorodrim was broken and Morgoth overthrown; and also some differences of tone and portrayal, some obscurities, and, here and there, some lack of cohesion. In the case of the Valaquenta, for instance, we have to assume that while it contains much that must go back to the earliest days of the Eldar in Valinor, it was remodelled in later times; and thus explain its continual shifting of tense and viewpoint, so that the divine powers seem now present and active in the world, now remote, a vanished order known only to memory.

The book, though entitled as it must be The Silmarillion, contains not only the Quenta Silmarillion, or Silmarillion proper, but also four other short works. The Ainulindal and Valaquenta, which are given at the beginning, are indeed closely associated with The Silmarillion; but the Akallabth and Of the Rings of Power, which appear at the end, are (it must be emphasised) wholly separate and independent. They are included according to my fathers explicit intention, and by their inclusion the entire history is set forth from the Music of the Ainur in which the world began to the passing of the Ringbearers from the Havens of Mithlond at the end of the Third Age.

The number of names that occur in the book is very large, and I have provided a full index; but the number of persons (Elves and Men) who play an important part in the narrative of the First Age is very much smaller, and all of these will be found in the genealogical tables. In addition I have provided a table setting out the rather complex naming of the different Elvish peoples; a note on the pronunciation of Elvish names, and a list of some of the chief elements found in these names; and a map. It may be noted that the great mountain range in the east, Ered Luin or Ered Lindon, the Blue Mountains, appears in the extreme west of the map in The Lord of the Rings. In the body of the book there is a smaller map: the intention of this is to make clear at a glance where lay the kingdoms of the Elves after the return of the Noldor to Middle-earth. I have not burdened the book further with any sort of commentary or annotation.

In the difficult and doubtful task of preparing the text of the book I was very greatly assisted by Guy Kay, who worked with me in 19741975.

Christopher Tolkien 1977

PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION

Probably towards the end of 1951, when The Lord of the Rings was completed but difficulties lay in the way of its publication, my father wrote a very long letter to his friend Milton Waldman, at that time an editor at the publishing house of Collins. The context and occasion of this letter lay in the painful differences that arose over my fathers insistence that The Silmarillion and The Lord of the Rings should be published in conjunction or in connexion as one long Saga of the Jewels and the Rings. There is however no need to enter into this matter here. The letter that he wrote with a view to justifying and explaining his contention emerged as a brilliant exposition of his conception of the earlier Ages (the latter part of the letter, as he himself said, was no more than a long and yet bald rsum of the narrative of The Lord of the Rings), and it is for this reason that I believe that it merits inclusion within the covers of The Silmarillion, as is done in this edition.

The original letter is lost, but Milton Waldman had a typescript made of it, and sent a copy to my father: it was from this copy that the letter was printed (in part) in The Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien (1981), no.131. The text given here is that in Letters, pp.143157, with minor corrections and the omission of some of the footnotes. There were many errors in the typescript, especially in names; these were very largely corrected by my father, but he did not observe the sentence on p.xviii: There was nothing wrong essentially in their lingering against counsel,