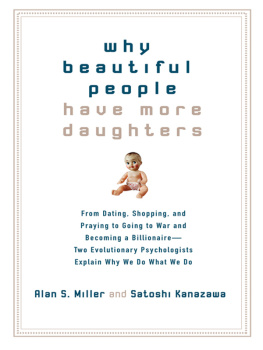

Copyright 2012 by Satoshi Kanazawa. All rights reserved

Credit, page 40: Sample item similar to those found in the Ravens Progressive Matrices (Advanced). Copyright 2007, 1976, 1962, 1947, 1943 NCS Pearson, Inc. Reproduced with permission. All rights reserved. Ravens Progressive Matrices and vocabulary scales is a trademark, in the US and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s).

Published by John Wiley & Sons, Inc., Hoboken, New Jersey

Published simultaneously in Canada

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, scanning, or otherwise, except as permitted under Section 107 or 108 of the 1976 United States Copyright Act, without either the prior written permission of the Publisher, or authorization through payment of the appropriate per-copy fee to the Copyright Clearance Center, 222 Rosewood Drive, Danvers, MA 01923, (978) 750-8400, fax (978) 646-8600, or on the web at www.copyright.com . Requests to the Publisher for permission should be addressed to the Permissions Department, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 111 River Street, Hoboken, NJ 07030, (201) 748-6011, fax (201) 748-6008, or online at http://www.wiley.com/go/permissions .

Limit of Liability/Disclaimer of Warranty: While the publisher and the author have used their best efforts in preparing this book, they make no representations or warranties with respect to the accuracy or completeness of the contents of this book and specifically disclaim any implied warranties of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. No warranty may be created or extended by sales representatives or written sales materials. The advice and strategies contained herein may not be suitable for your situation. You should consult with a professional where appropriate. Neither the publisher nor the author shall be liable for any loss of profit or any other commercial damages, including but not limited to special, incidental, consequential, or other damages.

For general information about our other products and services, please contact our Customer Care Department within the United States at (800) 762-2974, outside the United States at (317) 572-3993 or fax (317) 572-4002.

Wiley also publishes its books in a variety of electronic formats and by print-on-demand. Some content that appears in standard print versions of this book may not be available in other formats. For more information about Wiley products, visit us at www.wiley.com .

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Kanazawa, Satoshi.

The intelligence paradox : why the intelligent choice isn't always the smart one /

Satoshi Kanazawa.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-470-58695-2 (hardback); ISBN 978-1-118-13764-2 (ebk);

ISBN 978-1-118-13765-9 (ebk); ISBN 978-1-118-13766-6 (ebk)

1. Intellect. 2. Evolutionary psychology. I. Title.

BF431.K366 2012

153.9dc23

2011042289

For Kaja Perina ,

who makes all great things happen in my career

Acknowledgments

I first became interested in the problem of values when I was a student of Michael Hechter's at the University of Arizona. For my Ph.D. dissertation, I pursued an old theoretical problem that Michael had been interested in for many years, the Hobbesian problem of order (How is society possible among self-interested rational actors?). However, by the time I became his student in 1989, Michael was already beginning to move on to another project. He was trying to figure out where values and preferences of human actors came from. Rational choice theory can explain human behavior very well if it assumes what humans want and desire, but it cannot explain these wants and desires themselves. Michael, a leading rational choice theorist, wanted to advance the frontiers of rational choice theory by figuring out where human values and preferences came from, by providing a theoretical explanation for them. In technical language, he was trying to endogenize values in rational choice models.

I was not involved in Michael's values project at all, but was aware of the problem that he was struggling to solve. Even though Michael and I never discussed these theoretical issues, I was able to follow the contours and directions of his current thinking from the books and journal articles that he asked me to fetch from the library. On my long walks back from the main university library to the Social Sciences building, I would peruse the books and articles he wanted to read next. Sometimes I kept them for a couple of hours so that I could finish reading them before handing them to Michael.

Neither Michael nor I (nor anyone else) solved the problem of values, but the importance of the problem stayed with me. Years later, when I discovered evolutionary psychology by reading Robert Wright's The Moral Animal , I immediately realized that evolutionary psychology provided the answer that Michael had been searching for all these years. It could explain where human values and preferences came from. This book is the result of the realization.

My first and foremost intellectual debt is therefore to Michael Hechter, who unwittingly and unintentionally made me realize the importance of the problem of values and set me on this intellectual path. But I'm not sure how happy he is with the answer that I have found.

My intellectual life in London would be entirely barren but for a small group of like-minded scientists in and around London with whom I can share our mutual interest in evolutionary psychology and intelligence research. I thank Tomas Chamorro-Premuzic, Bruce G. Charlton, David de Meza, Adrian Furnham, Richard Lynn, Diane J. Reyniers, Jrn Rothe, Peter D. Sozou, and in particular Jay Belsky (who has since left London for greener intellectual pastures back in the United States) for years of stimulating discussions.

Since February 2008, I have had a blog at Psychology Today called the Scientific Fundamentalist ( http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-scientific-fundamentalist/ ). I've thrown out some of the ideas contained in this book initially on the blog, and they were subsequently developed, often with intellectual contributions from astute readers. I have a great team of editors at Psychology Today who have given tremendous support to me and my blog over the years. My warmest thanks go to Kaja Perina, Hara Estroff Marano, Carlin Flora, Lybi Ma, Wendy Paris, PT COO Charles Frank, PT Director of Business Development Batya Lahav, and PT CEO Jo Colman. I consider them all to be part of my extended intellectual family.

Kaja is responsible for recruiting me as one of the inaugural PT bloggers. In December 2007, blogging was the last thing in the world I wanted to do. I had always thought that there could not possibly be any value in doing something that anyone can (and apparently does) do, and that bloggers were the most idiotic and self-obsessed group of people. (After four years, I have not changed my opinion of bloggers. The only people who are stupider than bloggers are people who leave anonymous comments on blogs.) With one transatlantic phone call, Kaja changed my mind and got me to agree to sign up as one of the four inaugural PT bloggers. As it turns out, to my great surprise, blogging was something I could do, and I was somewhat good at it. As usual, Kaja knew me much better than I knew myself.

In the last nine years, since Kaja became Editor-in-Chief, Psychology Today has done more to popularize and promote evolutionary psychology to the general nonacademic public than we evolutionary psychologists have done ourselves. So the scientific community of evolutionary psychologists owes a great intellectual debt of gratitude to Kaja and her superb editorial staff at Psychology Today.