Stories about Stories

Stories about Stories

Stories about Stories

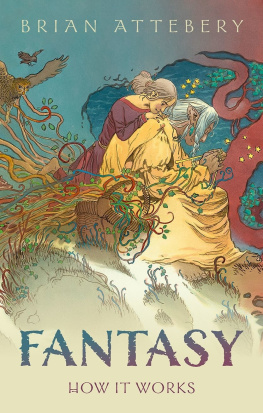

FANTASY AND THE REMAKING OF MYTH

Brian Attebery

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press

in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Brian Attebery 2014

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication

Data Attebery, Brian, 1951

Stories about stories: fantasy and the remaking of myth / Brian Attebery.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199316069 (hardcover: acid-free paper)ISBN 9780199316076

(pbk. : acid-free paper) 1. Fantasy literatureHistory and criticismTheory, etc.

2. Literature and myth. 3. Myth in literature. I. Title.

PN56.F34A88 2014

809.38766dc23 2013023205

9780199316069

9780199316076 (pbk.)

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

{ CONTENTS }

This book is the product of many conversations over the past dozen years, some of them with people I have yet to meet in person. I have benefitted greatly from the ideas and encouragement of Gary Wolfe, Farah Mendlesohn, Marek Oziewicz, Ursula K. Le Guin, Nalo Hopkinson, Michael Swanwick, John Clute, Tom Shippey, Greg Bechtel, Monty Vierra, Tiffany Martin, Delia Sherman, Kim Selling, Ellen Kushner, Grace Dillon, Chip Sullivan, Karen Joy Fowler, Jennifer Eastman Attebery, and all my colleagues at the Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts and Idaho State University. My thanks also to Idaho State University for sponsoring two sabbaticals, Uppsala University for hosting me as a visiting researcher, and many helpful librarians, including those at Sydney University and the Merril Collection.

Some chapters incorporate material from the following:

Stories Linked to Stories: Fantasy as a Route to Myth. Relevant across Cultures: Visions of Connectedness in Modern Fantasy Literature for Young Readers. Ed. Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak, Marek Oziewicz, and Agata Zarzycka. Wrocaw: Oficyna ydawnicza, 2009. 1931.

Exploding the Monomyth: Myth and Fantasy in a Postmodern World. Considering Fantasy: Ethical, Didactic, and Therapeutic Aspects of Fantasy in Literature and Film. Ed. Justyna Deszcz-Tryhubczak and Marek Oziewicz. Wrocaw: Oficyna Wydawnicza, 2007. 20920.

Aboriginality in Science Fiction. Science Fiction Studies 32 (2005): 385404.

Patricia Wrightson and Aboriginal Myth. Extrapolation 46 (2005): 32939.

High Church versus Broad Church: Christian Myth in George Mac-Donald and C. S. Lewis. The New York Review of Science Fiction 207 (Nov. 2005): 1417.

Myth and History: Molly Glosss Wild Life and Alan Garners Strandloper. The New York Review of Science Fiction 154 (June 2001): 1, 46.

Make It Old: The Other Mythic Method. Proceedings of the International Conference In the Mirror of the Past: Journeys from History to HISTORY.

My thanks to the original publishers for permission to reprint.

Fantasy can be tiny picture books or sprawling epics, formulaic adventures or intricate metafictions. The category includes some of the most popular imaginative creations of all timeJ. K. Rowlings Harry Potter, Terry Pratchetts Discworld, J. R. R. Tolkiens Middle-earthand some of the most obscure. Like any literary mode, it may be employed by great artists or hacks. It flatters readers by making them over into heroes, yet it also flattens their pretensions and challenges their deepest beliefs. Fantasy means fairy tales by Thackeray and Wilde and Dinesen, beast fables from Beatrix Potter to Franz Kafka, the nonsense of Lewis Carroll, the profound sense of Ursula K. Le Guin, the cosmic paranoia of H. P. Lovecraft, and the philosophical playfulness of Italo Calvino. The book of the twentieth century, according to a number of readers polls, was a fantasy, The Lord of the Rings. Other fantasies are as trivial and ephemeral as mayflies: Tolkien knockoffs and movie spinoffs.

Before any serious discussion of fantasy literature can take place, a number of obstacles must be cleared away. One is the problem of terminology: the same word gets bandied about in psychiatric sessions and literary discussions, not to mention titles of erotic romps on late-night cable TV. Another is the interchangeability of a lot of what is labeled fantasy on the supermarket book rack, much of it the unimpressive formula fiction that discerning fans call extruded fantasy product. The tremendous popularity of particular fantasy texts only tends to make those color-blind people even more resentful. And we cannot forget the book burners: people who consider fantasy of any stripe to be suspect on religious grounds, either because they believe it encourages witchcraft and devil worship or simply because it isnt true and therefore denies Creation.

, but I should note that here and throughout this book, myth is used to designate any collective story that encapsulates a world view and authorizes belief. Thus Christian myth includes the Creation accounts and flood story from Genesis; the cycle of incarnation, atonement, and resurrection from the Gospels; the Apocalypse; and various medieval embroideries on those, such as the story of Adams first wife Lilith. The problem for literalists is not that fantasy denies Christian myths but that it rearranges, reframes, and reinterprets them. Fantasy is fundamentally playfulwhich does not mean that it is not serious. Its way of playing with symbols encourages the reader to see meaning as something unstable and elusive, rather than single and self-evident.

Furthermore, not all fantasy derives from biblical narratives or Christian symbols. This is either a problem or a redeeming virtue, depending on ones religious orientation. Modern fantasy draws on a number of traditional narrative genressacred and secular legends, Mrchen, epics, and balladsand a wide array of cultural strands, including pre-Christian European, Native American, indigenous Australian, and Asian religious traditions. For my purposes, and taking a cue from Jacob Grimm, I also use myth as an umbrella term over these various traditional forms, although I do not subscribe to his belief that peasant tales were the diminished remnants of a Teutonic mythology. Rather, magical tales and supernatural ballads share with hero legends and stories of creation a sense of mystery and meaning that can be exploited by modern storytellers. Since the time of the Grimms, fantasy writers have treated all those oral genres as part of a single resource: different veins in the same mother lode of symbolic narrative. A motif from a saints legend can be incorporated into an imitation of a wonder tale. Tolkiens English epic,

Next page