James Enge

This Crooked Way

The second book in the Ambrose series

The epigraph for chapter IV is from the version of Gilgamesh by N. K. Sanders (Penguin, 1960). The epigraph for chapter XVI is from the translation of Sophocles' Antigone by Dudley Fitts and Robert Fitzgerald (Harcourt Brace & Co., 1939).

Some of these chapters appeared, in somewhat different form, in the fantasy magazine Black Gate. Thanks are due the editors, John O'Neill and Howard A. Jones-how many, they know and I haven't words to say.

"Now, Sirs," quod he, "If that you be so lief

To finde Death, turn up this crooked way,

For in that grove I left him, by my fey,

Under a tree, and therehe will abide;

Not for your boast he will him nothing hide."

CHAUCER, "THE PARDONER'S TALE"

I

THE WAR IS OVER

NOR, WHEN THE WAR IS OVER, IS IT PEACE; NOR WILL THE VANQUISHED BULL HIS CLAIM RELEASE: BUT FEEDING IN HIS BREAST HIS ANCIENT FIRES AND CURSING FATE, FROM HIS PROUD FOE RETIRES.

VERGIL, GEORGICS

The crooked man rode out of the dead lands on a black horse with gray sarcastic eyes.

Winter was awaiting him, as he expected. In the dead lands it never rained or snowed, and the nearness to the sea kept the lifeless air mild. But it was the month of Brenting, late in winter, and as they crossed into the living lands the air took on a deadly chill and the snowdrifts soon became knee-high on his horse.

Morlock Ambrosius dismounted awkwardly and took the reins in his hand. "Sorry about this, Velox," he said to the horse.

Velox looked at him and made a rude noise with his lips.

"Eh," Morlock replied, "the same to you," and floundered forward through the snowdrifts, leading the beast. He was a pedestrian by temperament and had spent much of his long life walking from one place to another. He knew little about the care of horses, and what little he knew was not especially useful, as Velox was unusual in a number of ways. But, although he had considered it, he found he could not simply abandon Velox or trade him to some farmer for a basket of flatbread.

But Velox wanted food in alarming horse-sized amounts. Morlock had tried feeding him dried seaweed from the coastline, and Velox had eaten it, since there was little else. But Morlock suspected it wasn't enough for the grumpy beast, and he was going to have to go to a farm or even a town to buy some horse feed.

This was a problem, as Morlock was a criminal in the eyes of imperial law. He had reason to suppose the Emperor was not interested in seeing him dead, but no local Keeper of the Peace was likely to know this. It was dangerous for him to be seen, to be recognized.

On the other hand, his horse was hungry.

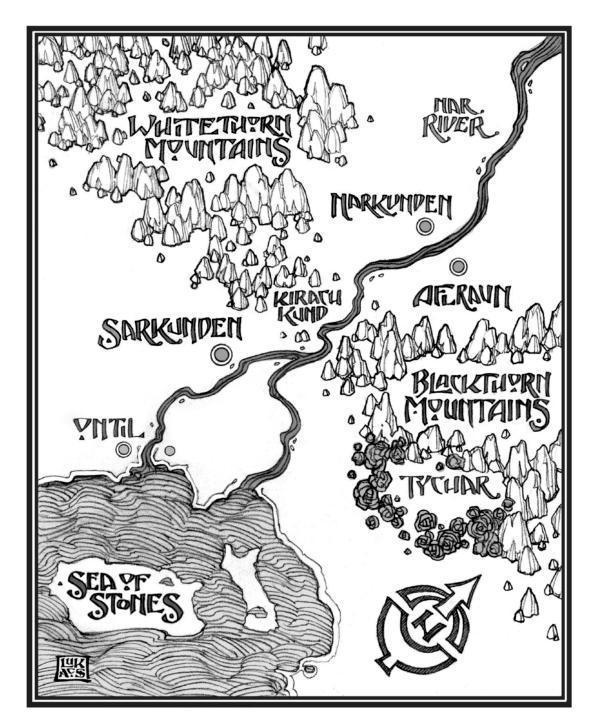

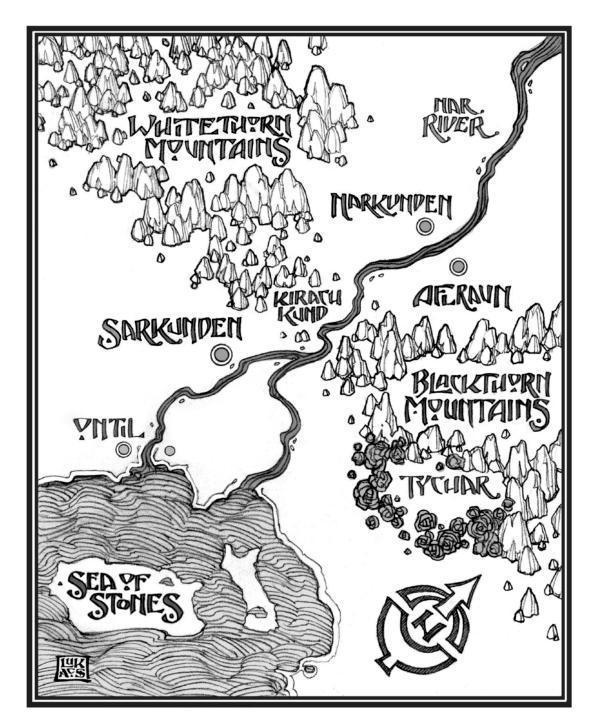

Nearly as grumpy as Velox, Morlock led the beast eastward through the bitter white fields until they reached the black muddy line of the Sar river, running south from the Kirach Kund. Alongside the river ran a hardly less muddy road; at intervals on the road were stations of the Imperial Post; clustering around some of these stations were towns where one could buy amenities like hay and oats.

Morlock mounted his horse and rode north toward Sarkunden. Presently he came, not to a town, but (even better for his purposes) to a barn. The doors of the barn were open and several dispirited farm workers were carrying pails of dung out of the barn and dumping it in a dark steaming heap that contrasted strangely with the recent snow.

Morlock reined in and said, "Good day. Can I buy some oats or something?"

The workers stopped their work and stared at him. Others came out of the barn, and also stopped and stared. After a while, one who seemed to be their leader (or thought he was), said, "Not from us, Crookback."

"Do you own this place?" Morlock asked.

"No, but we'll keep him from selling to you."

"Unlikely," Morlock replied, and dismounted. The men were gripping their dungforks and shovels and whatnot more like weapons now. If there was going to be a fight he wanted to be on his own feet, for a number of reasons.

"Know who I am, Crookback?" the leader of the workmen asked.

"No."

"This help?" He brushed some muck off his darkish outer garment. Morlock saw it was embroidered with a red lion.

"Not much," Morlock said.

"My name is Vost. I was Lord Urdhven's right-hand man. His closest friend. You killed him. Destroyed him. And now you come here. And ask me for oats."

"The man was dead before I met him," Morlock said. "We've no quarrel."

"You lie," Vost said, sort of, through clenched teeth.

"Then," Morlock replied. He drew the sword strapped to his crooked shoulders. The crystalline blade, black entwined with white, glittered in the thin winter sunlight.

"I hate you," Vost hissed, raising the dungfork in his hands like a stabbing spear. "I hate you. Nothing will stop me from trying to kill you until you're dead."

Morlock believed him. He was beginning to remember this Vost a little: a fanatical devotee of the late unlamented Lord Protector Urdhven; he had lived and died by his master's expressions of favor or disfavor. His life had lost its meaning when he had lost his master, and he had to blame someone for his freedom. Evidently he had settled on Morlock.

Morlock extended his sword arm and lunged, stabbing the man through his ribs. Vost's face stretched in surprise, then went slack with death. Morlock felt the horror of his dissolution through the medium of his sword, which was also a focus of power, very dangerous to use as a mundane weapon. A dying soul wants to carry others with it, and Morlock had to free himself of Vost's death shock and the dead soul's death grip before he was free to shake the corpse off the end of his sword and face Vost's companions.

They must have made some move toward attacking him, because Velox was in amongst them, rearing and kicking. One man already lay still in the dirty snow, a dark hoofmark on his forehead. As Morlock turned toward them, his sword dripping with Vost's blood and his face clenched in something not far removed from death agony, they took one look and fled, running up the road past the barn.

"Hey!" shouted a man coming out of the farmhouse with an axe in his hand. He was a prosperous gray-haired man with darkish skin, and he carried the axe like he knew how to use it. "Why are you killing my workmen?"

Morlock was cleaning his blade with some snow; he wiped it on his sleeve and sheathed it.

"The man annoyed me," he said at last.

"And the other one?"

"Annoyed my horse."

"You know what annoys me? People who come into my barnyard and leave dead bodies lying all over the place. I find that annoying."

"I was going to dump them into the river. Unless you have some strong objection."

The farmer blew out his cheeks and thought it over. "No, I guess not. They were no friends of mine, just some tramps working for the day."

"Then." Morlock hauled Vost's corpse out of the yard, across the road, and threw it face down into the muddy water of the Sar. The corpse sank almost out of sight; the sluggish waters tugged it away from the bank and it floated downstream. The last casualty in Protector Urdhven's civil war, or so Morlock hoped.

When he returned, he found the farmer had laid down his weapon and was crouching over the workman Velox had struck down. "This one's still breathing," the farmer said. "Your horse is hurt, though."