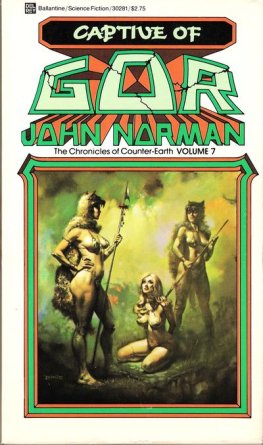

CAPTIVE OF GOR

(Volume seven in the Chronicles of Counter-Earth)

by John Norman

The following account is written at the command of my master, Bosk of Port Kar, the great merchant, and, I think, once of the warriors.

My name was Elinor Brinton. I had been independently wealthy.

There is much I do not understand. Let others find what meaning they can in this narrative.

I gather that my story is neither as unique, nor as strange, as it may seem. By the standards of Earth, I was regarded as extremely beautiful. Yet on this world I am a fifteen-goldpiece girl, more lovely than many, yet far excelled by many whose stunning beauty I can only envy. I was purchased for the kitchens of the house of Bosk. Traders, I have learned, ply the slave routes between this world and Earth. Women, among other goods, are acquired and brought to the markets of this strange world. If you are beautiful, and desirable, you many fear. Apparently they may do what they wish.

Yet I think there are perhaps worse fates that might befall a woman than to be brought to this world, even as a prize of men.

My master has told me not to describe this world in great detail. I do not know why that is, but I shall not do so. He has told me to narrate primarily what has occurred to me. And he has asked me to put down my thoughts and, particularly, my emotions. I wish to do so. Indeed, even if I did not wish to do so, I would have to obey.

Suffice it then to say but little of my background and condition.

I was expensively educated, if not well educated. I endured a succession of lonely years at boarding schools, and later at one of the finest women's colleges in the northeastern portion of the United States. These years seem to me now oddly empty, even frivolous. I had had no difficulty in obtaining fine grades. My intelligence, it seems to me, was good, but even when my work seemed to me inferior, it was rated highly, as indeed, was that of my sorority sisters. Our parents were wealthy and substantial grants to the schools and colleges were often made following our graduations. Also, I had never found men, and many of my instructors were such, hard to please. Indeed, they seemed eager to please me. I was failed in one course, in French. My instructor in this case was a woman. The Dean of Students, as was his wont in such circumstances, refused to accept the grade. I took a brief examination with another instructor, and the grade became an A. the woman resigned from the school that Spring. I was sorry, but she should have known better. As a rich girl I had little difficulty in making friends. I was extremely popular. I do not recall anyone to whom I could talk. My holidays I preferred to spend in Europe.

I could afford to dress well, and I did. My hair was always as I wanted it, even when it appeared, deceptively, as most charmingly neglected. A bit of ribbon, a color on an accessory, the proper shade of expensive lipstick, the stitching on a skirt, the quality of leather in an imported belt and matching shoes, nothing was unimportant. When pleading for an extension for an overdue paper I would wear scuffed loafers, blue jeans and a sweatshirt, and hair ribbon. I would at such times smudge a bit of ink from a typewriter ribbon on my cheek and fingers. I would always get the extra time I needed. I did not, of course, do my own typing. Usually, however, I wrote my own papers. It pleased me to do so. I liked them better than those I could purchase. One of my instructors, from whom I had won an extension in the afternoon, did not recognize me the same evening when he sat some rows behind me at a chamber music performance at the Lincoln Center. He was looking at me quizzically, and once, during an intermission, seemed on the point of speaking. I chilled him with a look and he turned away, red faced. I wore black, an upswept hairdo, pearls, white gloves. He did not dare look at me again.

I do not know when I was noticed. It may have been on a street in New York, on a sidewalk in London, at a cafA in Paris. It may have been while sun-bathing on the Riviera. It may even have been on the campus of my college. Somewhere. Unknown to me, I was noted, and would be acquired.

Affluent and beautiful, I carried myself with a flair. I knew that I was better than most people, and was not afraid to show them, in my manner, that this was true. Interestingly, instead of being angered, most people, whatever may have been their private feelings, seemed impressed and a bit frightened of me. They accepted me at the face value which I set upon myself, which was considerable. They would try to please me. I used to amuse myself with them, sometimes pouting, pretending to be angry or displeased, then smiling to let them know that I had forgiven them. They seemed grateful, radiant. How I despised them! They bored me. I was rich, and fortunate and beautiful. They were nothing. My father made his fortune in real estate in Chicago. He cared only for his business, as far as I know. I cannot remember that he ever kissed me. I do not r ecall seeing him, either, ever touch my mother, or she him, in my presence. She came from a wealthy Chicago family, with extensive shore properties. I do not believe my father was even interested in the money he made, other than in the fact that he made more of it than most other men, but there were always others, some others, who were richer than he. He was an unhappy, driven man. I recall my mother entertaining in our home. This she often did. I recall my father once mentioning to me that she was his most valuable asset. He had meant this to be a compliment. I recall that she was beautiful. She poisoned a poodle I had once had. It had torn one of her slippers. I was seven at the time, and I cried very much. It had liked me. When I graduated neither my mother nor my father attended the ceremony. That was the second time in my life, to that time, that I remember crying. He had a business engagement, and my mother, in New York, where she was then living, was giving a dinner for certain of her friends. She did send a card and an expensive watch, which I gave to another girl.

That summer my father, though only in his forties, died of a heart attack. As far as I know my mother still lives in New York City, in a suite on Park Avenue. In the settlement of the estate my mother received most everything, but I did receive some three quarters of a million dollars, primarily in stocks and bonds, a fortune which fluctuated, and sometimes considerably, with the market, but one which was substantially sound. Whether my fortune on a given day was something over three quarters of a million dollars did not much interest me.

Following my graduation I took up my own residence, in a penthouse on Park Avenue. My mother and I never saw one another. I had no particular interest in anything following school. I smoked too much, though I hated it. I drank quite a bit. I never bothered with drugs, which seemed to me stupid.

My father had had numerous business contacts in New York, and my mother had made influential friends. I made a rare phone call to my mother a few weeks after my graduation, thinking it might be interesting to take up modeling. I had thought there might be a certain glamour to that, and that I might meet some interesting and amusing people. A few days later I was invited to two agencies for interviews, which, as I expected, were mere formalities. There are doubtless, many girls beautiful enough to model. Beauty, in itself, in a population numbering in the tens of millions, is not difficult to find. Accordingly, particularly with unexperienced girls, one supposed that criteria other than beauty and charm, and poise, often determines one's initial chances in such a competitive field. It was so in my case. I believe, of course, that I could have been successful on my own as well. But I did not need to be.