No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior permission of the publishers.

Canine Beginnings

The problem facing everyone who writes about dogs is that there are thousands, if not millions, of people who have already done so. Like dogs themselves, dog literature abounds and, in part because of this wealth of materials, dog books tend to lose in coherence what they gain in comprehensiveness. In attempting to reconcile too much information, such texts take on a randomness that even those of us who call ourselves dog people find tedious. Predictably, these documents of dogs frustrate even the most comprehensive attempts at categorization, and threaten to rub our noses in the mess we make of understanding dogs. But in their chaos they also remain faithful to our confusing (sometimes confused) experiences with canine companions. The difficulty of representing dogs let alone accounting for how they have become a central part of the human experience reflects the ongoing struggle of defining what a dog is.

Narrowing the subject to the most familiar kind, domesticated dogs or Canis familiaris, helps only slightly. This group of animals has the largest range of body types and sizes of any mammal, ranging anywhere from 0.5 to 100 kilos (1 to 250 lb), any combination of which can produce fertile offspring; the broadest geographic range of all four-footed creatures (their populations are second only to humans in worldwide distribution); the longest history of human domestication of any ) Taken together, the wide-ranging morphology, distribution, history and reproductive physiology of the dog boggle the human imagination.

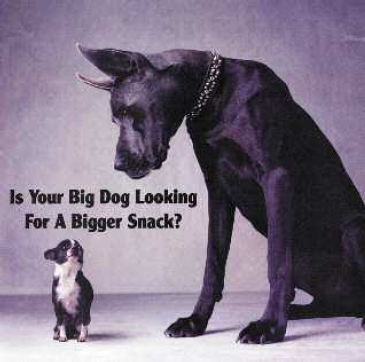

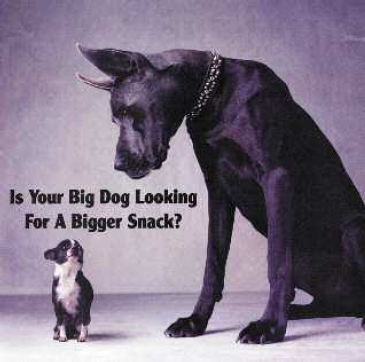

Advertisement in the Maine Sunday Telegram (2 March 2003). |

|

But if these qualities hinder definitive representations of dogs they also secure room for play in the process of representing them. The size differences between familiar breeds such as chihuahuas and Great Danes, for instance, enable a dog-eat-dog visual pun in a current ad for Jumbone dog snacks; the ad implies that if you dont do your part as a consumer, then your big dog might literally consume a smaller one. More subtly, the ad presents a product that itself attests to the decisive role of mass marketing in the long history of canine adaptation to human cohabitation. A descendent of the first commercially prepared food specifically marketed for pets a dog biscuit introduced 150 years ago in Britain the dog snack ad also figures a shared modern history in which the dog moves from primarily working animal to pet. Although such uses of dogs have become so common as to seem banal, they clearly draw from the same canine complexity that has inspired the human imagination to forge new modes and methods of expression, across thousands of years and in nearly every corner of the world. If their chaotic omnipresence causes headaches for librarians and researchers, it also ensures the central cultural work of dogs in complicating rather than resolving questions of representation.

Reflecting an enormous range of social practices, the material evidence of dogs in our lives, though daunting, becomes all the more compelling even for non-doggy people those who do not put their trust in dogs when considering how it corresponds directly to large populations of these creatures. Since their archives as a whole are but poorly understood, dogs themselves must suffer from our confused and conflicted understanding of their significance. The dangers for contemporary dogs are real: destroyed by the millions every year as unwanted pets, strays and research subjects, domesticated dogs bear the double-bind of sharing many of the maladies as well as the joys of living the so-called good life, and they are also subjected to the mass killings that the worlds poorest people and the majority of all animal species now suffer on an unprecedented scale. Intersecting with humans ideas of each other, the long histories of conflicting attitudes towards dogs illuminate these lived contradictions.

a criticism both unselfconsciously and ironically applied to dogs. Seen as a comic grotesque, Goofy is akin to the stock animal characters of American blackface minstrelsy such as Zip Coon, which were rapidly being relocated from stage to cartoon at the time of their inception. Today, as Disney products find markets across the world, these interlocked extremes Goofys Rover and Plutos Fido not only evoke strong emotions about dogs but also bear histories of cultural differences that colour viewers relationships with other animals as well as each other.

Fortunately, the omnipresence of the canine race inspires constant scrutiny of these ideas as well. Both clothed clown and naked mute, the fluctuating dog in this doubled Disney vision is a testament to the creation and malleability of canine archetypes: in the twentieth century Fido became an acronym both for flawed coins and fog-dispersal systems, while Rover became the first canine film star and a popular pet name through the film of 1904, Rescued by Rover. Together, these extreme characterizations serve as a powerful object lesson in anthropomorphism, of the projection of ideas of the human into animal bodies. But their ongoing rebirth in Disney dog characters The Shaggy Dog, 101 Dalmations, Air Bud serialized and remade, decade after decade, in turn reflects the inherent instability of the natural and cultural status of not only animals but also humans. Goofy and Pluto may lead the pack of popular dog characters, but they do not simply reflect or instil stable hierarchies of social difference. Often such characters even inspire critiques of existing social relationships as well as help us to imagine new ones.

To gain insight into how dogs gain this pivotal position, this book poses some questions about historic approaches to writing and thinking about dogs, tracing how and when dogs operate as aesthetic, sexual and scientific objects as well as paying close attention to the more rarefied moments when dogs contribute to historic transformations in society and culture. This chapter focuses specifically on the contested beginnings, namely the emergence of these most familiar canids at the dawn of human civilization, to show how conflicting theories of their biological origins intersect with broader philosophical and linguistic approaches to defining dogs. As an animal that emerges between (and sometimes interbreeds with) others, the dog presents special challenges to species-centred notions of history. Consequently, the various canine origin myths across the arts and sciences highlight not just the problems of dogs placement within taxonomies. Although it may be easy to accept that popular cultural representations of dogs are purposeful distortions of some natural, common-sense reality, these in turn stem from a construction of this very nature of dogs that traces specific conflicts of and within human cultures throughout recorded time.