The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2002 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2002

Paperback edition 2003

Printed in the United States of America

19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11 10 6 7 8 9 10

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90137-4 (e-book)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-90135-0

ISBN-10: 0-226-90135-1

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Wilson, David Sloan.

Darwins cathedral : evolution, religion, and the nature of society / David Sloan Wilson.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references (p. ).

ISBN 0-226-90134-3 (cloth : alk. paper)

ISBN 978-0-226-90137-4 (e-book)

1. Religion and sociology. 2. Group selection (Evolution) I. Title.

BL60.W544 2002

306.6dc21

2002017375

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

DARWINS CATHEDRAL

EVOLUTION, RELIGION, AND THE NATURE OF SOCIETY

DAVID SLOAN WILSON

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

Chicago and London

CONTENTS

But now at least he understood his religion: its essence was the relation between man and his fellows.

Isaac Bashevis Singer

INTRODUCTION

CHURCH AS ORGANISM

True love means growth for the whole organism, whose members are all interdependent and serve each other. That is the outward form of the inner working of the Spirit, the organism of the Body governed by Christ. We see the same thing among the bees, who all work with equal zeal gathering honey.

Ehrenpreis [1650] 1978, 11

Religious believers often compare their communities to a single organism or even to a social insect colony. The passage quoted above is from the writings of the Hutterites, a Christian denomination that originated in Europe five centuries ago and that currently thrives in communal settlements scattered throughout northwestern North America. Beehives are pictured on the road signs of the Mormon-influenced state of Utah. Across the world in China and Japan, Zen Buddhist monasteries were often constructed to resemble a single human body (Collcutt 1981).

The purpose of this book is to treat the organismic concept of religious groups as a serious scientific hypothesis. Organisms are a product of natural selection. Through countless generations of variation and selection, they acquire properties that enable them to survive and reproduce in their environments. My purpose is to see if human groups in general, and religious groups in particular, qualify as organismic in this sense.

Science works best when a subject can be resolved into well-framed hypotheses that make different predictions about measurable aspects of the world. Unfortunately, many subjects have a long hard road to travel before they reach that exalted state. The organismic concept of society has had an especially difficult journey. To some it is so self-evident that it scarcely requires testing. To others it is so far-fetched that it deserves mockery more than serious consideration. When smart people disagree to this extent, it is often because they are speaking different languages. Indeed, when one studies the organismic concept of society across time and disciplinary boundaries, one encounters a Tower of Babel. I am therefore faced with a second task almost as challenging as my first. Before I can treat the organismic concept of religious groups as a serious scientific hypothesis, I must provide a translation manual that allows meaningful communication across diverse fields of thought.

My inquiry requires equal attention to biology and to the vast literature devoted to our own species. Evolutionary theory explains how social groups can be like individuals in the harmony and coordination of their parts. Testing evolutionary theory requires a detailed knowledge of organisms in relation to their environment. When the organisms are religious groups, this means tackling an enormous literature from fields as diverse as theology, history, anthropology, sociology, and psychology. No one who has confronted this literature can claim to have mastered it, but I have made a solid effort and I expect to be judged by professional standards.

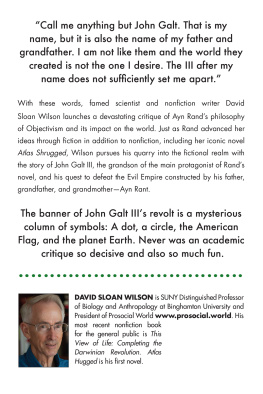

Evolutionary theories of human behavior often provoke great skepticism and hostility, inside and outside the ivory tower. Surprisingly, my own interactions with skeptics of all stripes are usually cordial and productive. One reason is that I approach others as a student rather than as a teacher. It is I who have much to learn from them, and if they also learn from my evolutionary perspective, so much the better. Another reason is that I agree with many of the criticisms leveled against past evolutionary theories of human behavior. I do not believe that human nature is fundamentally selfish, such that genuine altruism and morality become illusions. I do not believe that human nature can be explained entirely in terms of genetic evolution, such that it was set in stone during the Stone Age. I regard human evolution as a rapid and ongoing process, made possible by mechanisms loosely described as cultural, which means that human nature will never be set in stone, for better or for worse. Above all, I do not share the hostility that many evolutionists have expressed toward religion, from Huxley (1863) to Dawkins (1998).

A word about the scope of this book and the audience for which it is intended. Understanding religion requires answers to questions that extend beyond religion. What is the nature of human society? Is it a collection of self-seeking individuals, or can it be regarded as an organism in its own right? These questions have been pondered by inquiring minds throughout the ages, with no more agreement today than 500 or 2,000 years ago. Perhaps such big questions have no answers, forever remaining matters of opinion. Call me audacious, but I believe that they do have answers, based on developments in evolutionary biology that are only a few decades old. This book has been written for anyone who has wondered about the organismic nature of human society, regardless of their academic training or interest in religion per se.

I also hope that this book will be read by religious believers, despite its resolutely scientific approach to religion. Spirituality is in part a feeling of being connected to something larger than oneself. Religion is in part a collection of beliefs and practices that honor spirituality. A scientific theory that affirms these statements cannot be entirely hostile to religion. I frankly admire many features of religion, without denying the many horrors that have also been committed in its name. Indeed, the hypothesis presented in this book explains the mix of blessings and horrors associated with religion better than any other hypothesis, or so I claim.

Religion is sometimes defined as a belief in supernatural agents. However, other people regard this definition as shallow and incomplete. The Buddha refused to be associated with any gods. He merely claimed to be awake and to have found a path to enlightenment. I am aware that Buddhism as actually practiced is often chock full of gods, but the opinion of its founder is still relevant. If there is more to religion than belief in supernatural agents, then perhaps science is not as hostile to religion as it is often taken to be. One reason that I admire some aspects of religion is because I share some of its values. I have not attempted to hide this fact, and I hope that it has not intruded upon my science. Nor have I attempted to conceal my own basic optimism that the world can be a better place in the future than in the past or presentthat there can be such a thing as a path to enlightenment. Being a scientist does not require becoming indifferent to human welfare.

Next page

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.