THE COMPUTER & THE BRAIN

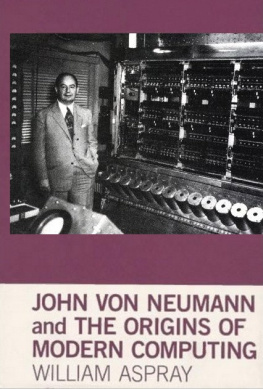

JOHN

VON

NEUMANN

THE COMPUTER & THE BRAIN

FOREWORD BY RAY KURZWEIL

THIRD

EDITION

NEW HAVEN

& LONDON

First edition 1958.

Second edition published as a Yale Nota Bene book in 2000.

Third edition 2012.

Copyright 1958 by Yale University Press.

Copyright renewed 1986 by Marina V. N. Whitman.

Foreword to the Second Edition copyright 2000 by Yale University.

Foreword to the Third Edition copyright 2012 by Ray Kurzweil.

All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part,

including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections

107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public

press), without written permission from the publishers.

Yale University Press books may be purchased in quantity for educational,

business, or promotional use. For information, please e-mail sales.press@yale.edu

(U.S. office) or sales@yaleup.co.uk (U.K. office).

Printed in the United States of America.

Library of Congress Control Number: 2011943281

ISBN 978-0-300-18111-1 (pbk.)

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

Frontispiece: Adapted from White Matter Tracks Image #20 from the HCP.

Courtesy of Arthur W. Toga and Vaughan Greer at the Laboratory of Neuro

Imaging at UCLA; Randy Buckner, Bruce Rosen, and Van J. Wedeen at the

Martinos Center for Biomedical Imaging at MGH; Consortium of the Human

Connectome Project.

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

THE SILLIMAN FOUNDATION LECTURES

On the foundation established in memory of Mrs. Hepsa Ely Silliman, the President and Fellows of Yale University present an annual course of lectures designed to illustrate the presence and providence of God as manifested in the natural and moral world. It was the belief of the testator that any orderly presentation of the facts of nature or history contributed to this end more effectively than dogmatic or polemical theology, which should therefore be excluded from the scope of the lectures. The subjects are selected rather from the domains of natural science and history, giving special prominence to astronomy, chemistry, geology, and anatomy.

FOREWORD TO THE THIRD EDITION

Information technologies have already transformed every facet of human life from business and politics to the arts. Given the inherent exponential increase in the price-performance and capacity of every form of information technology, the information age is continually expanding its sphere of influence. Arguably the most important information process to understand is human intelligence itself, and this book is perhaps the earliest serious examination of the relationship between our thinking and the computer, from the mathematician who formulated the fundamental architecture of the computer era.

In a grand project to understand the human brain, we are making accelerating gains in reverse engineering the paradigms of human thinking, and are applying these biologically inspired methods to create increasingly intelligent machines. Artificial intelligence (AI) devised in this way will ultimately soar past unenhanced human thinking. My view is that the purpose of this endeavor is not to displace us but to expand the reach of what is already a human-machine civilization. This is what makes our species unique.

So what are the key ideas that underlie this information age? By my count there are five. John von Neumann is largely responsible for three of them, and he made a fundamental contribution to a fourth. Claude Shannon solved the fundamental problem of making information reliable. Alan Turing demonstrated and defined the universality of computation and was influenced by an early lecture by von Neumann. Building on Turing and Shannon, von Neumann created the von Neumann machine, which becameand remainsthe fundamental architecture for computation.

In the deceptively modest volume you are now holding, von Neumann articulates his model of computation and goes on to define the essential equivalence of the human brain and a computer. He acknowledges the apparently deep structural differences, but by applying Turings principle of the equivalence of all computation, von Neumann envisions a strategy to understand the brains methods as computation, to re-create those methods, and ultimately to expand its powers. The book is all the more prescient given that it was written more than half a century ago when neuroscience had only the most primitive tools available. Finally, von Neumann anticipates the essential acceleration of technology and its inevitable consequences in a coming singular transformation of human existence. Lets consider these five basic ideas in slightly more detail.

Around 1940, if you used the word computer, people assumed you were talking about an analog computer. Numbers were represented by different levels of voltage, and specialized components could perform arithmetic functions such as addition and multiplication. A big limitation, however, was that analog computers were plagued by accuracy issues. Numbers could be represented with an accuracy of only about one part in a hundred, and because voltage levels representing numbers were processed by increasing numbers of arithmetic operators, these errors would accumulate. If you wanted to perform more than a handful of computations, the results would become so inaccurate as to be meaningless.

Anyone who can remember the days of copying music using analog tape will remember this effect. There was noticeable degradation on the first copy, for it was a little noisier than the original (noise represents random inaccuracies). A copy of the copy was noisier still, and by the tenth generation, the copy was almost entirely noise.

It was assumed that the same problem would plague the emerging world of digital computers. We can see this perceived problem if we consider the communication of digital information through a channel. No channel is perfect and will have some inherent error rate. Suppose we have a channel that has a 0.9 probability of correctly transmitting each bit of information. If I send a message that is one-bit long, the probability of accurately transmitting it through that channel will be 0.9. Suppose I send two bits? Now the accuracy is 0.92 = 0.81. How about if I send one byte (eight bits)? I have less than an even chance (0.43, to be exact) of sending it correctly. The probability of accurately sending five bytes is about 1 percent.

An obvious approach to circumvent this problem is to make the channel more accurate. Suppose the channel makes only one error in a million bits. If I send a file with a half million bytes (about the size of a modest program or database), the probability of correctly transmitting it is less than 2 percent, despite the very high inherent accuracy of the channel. Given that a single-bit error can completely invalidate a computer program and other forms of digital data, that is not a satisfactory situation. Regardless of the accuracy of the channel, since the likelihood of an error in a transmission grows rapidly with the size of the message, this would seem to be an intractable problem.

Analog computers approach this problem through graceful degradation. They also accumulate inaccuracies with increased use, but if we limit ourselves to a constrained set of calculations, they prove somewhat useful. Digital computers, on the other hand, require continual communication, not just from one computer to another, but within the computer itself. There is communication between its memory and the central processing unit. Within the central processing unit, there is communication from one register to another, and back and forth to the arithmetic unit, and so on. Even within the arithmetic unit, there is communication from one bit register to another. Communication is pervasive at every level. If we consider that error rates escalate rapidly with increased communication and that a single-bit error can destroy the integrity of a process, digital computation is doomedor so it seemed at the time.

Next page