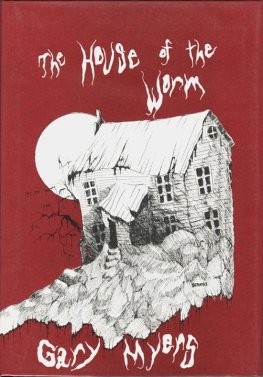

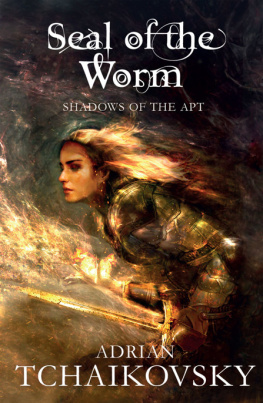

Gary Myers

The House of the Worm

Chapter One of this book is not a major contribution to the Cthulhu Mythos of H. P. Lovecraft, as expounded by his friend and publisher, the late August Derleth, but it does present an interesting heresy.

According to Derleth, the central precept of the Cthulhu Mythos is that the evil Great Old Ones once made war on the benign Elder Gods, and were banished by Them to outer darkness, where they abide the hour of their resurgence. The body of Mythos lore recounts the modern manifestations of the Ancient Ones trying to return. The theme of resurgence is an important one in Lovecraft, and the Great Old Ones are his invention, though other writers have added to the pantheon; but the Elder Gods, with the exception of Nodens, are entirely the creation of August Derleth.

Only Lovecraft is scripture. Elder Ones, at least, are mentioned with Nodens in The Strange High House in the Mist; but the Elder Ones are younger than infinitys Other Gods, who came to dance on Hatheg-Kla before the gods or even the Elder Ones were born. And Kuranes, in The Dream-Quest of Unknown Kadath, identifies the Elder Ones with the Great Ones of Kadath, who carved their own anthropomorphic likeness on Ngranek. It was the Great Ones who banished the Gugs to caverns below because of their sacrifices to Nyarlathotep and the Other Gods. But the Other Gods are the ultimate gods even in the opinion of the priests of Nasht and Kaman-Thah, as Lovecraft states plainly. Probably the Great Ones had more than one reason for desiring to escape from Kadath, and Nyarlathotep for keeping them there. Protection by the Other Gods is refined cruelty.

This is all very far from Derleth, but also from the Cthulhu Mythos proper. Gates between the dreamlands and our own world are numerous but obscure, and developments there cannot change the pattern of the Mythos on this side of the seventy onyx steps.

The Great Old Ones of this book are the Other Gods and their affiliates, but the Elder Gods are only a somewhat optimistic appraisal of the Great Ones of Kadath. Man has frankly biased opinions about the ordering of his universe and the obligations of his gods toward himself; the gods, being mindless, have no opinions, or else they have found that obligations can be evaded successfully merely by swallowing whoever would call them to their attention. The cotters of Vornai are orthodox Derlethians, but the Worm is notoriously a skeptic.

Gary Myers

South Gate, California April 1974

CHAPTER I

The House of the Worm

The house lies in ruin. Time and the elements have used it cruelly, and now have left it to perish dismally. They have left it to its loneliness; there is only silence in its empty halls, and the tittering of rats. The crumbling walls are effaced by leprous white fungi and scaly lichens; the dust of years lies thick on the rotting floors. The windows, once lit with a thousand twinkling lights, now are dark and boarded; all save two, and these are lightless as the sockets in a yellowed skull.

But for a single moment at evening, when the last ray of a dying sun touches on those two lozenge windows, the House wakes to stare into the night with eyes that shine red strangely long after the sun has passed, and perhaps dreams. Of what should a house dream? Of the past, maybe, of the time when it was young, when colourful pageants of men and women passed like players on a stage, and lived their lives as lives should be lived, and died? Perhaps; but now only the rats live here, and such memories are but the frail ghosts of forgotten years, beyond recall. Indeed, for the House of the Worm they never existed.

The House dreams of older things. For the House is far older than the mouldering timbers and crumbling masonry, the silence and the dank mildew. These are old indeed, but they are built on foundations whose age no man remembers and no record tells. They are akin to the works of the Great Ones of Kadath maybe those five monoliths of black stone, graven with maddening symbols and curious runes, set in the hill as on the five points of a star but they were ancient when Kadath lay yet unquarried, ancient ere men ever crawled from the slime of abyssmal seas, ancient even in that unutterable time when the wise Old Ones guessed vainly at their origin. Their antiquity was only dim legend, and doubted as legends are, when the timbers and the masonry were first raised by that Old Man of Whom No One Likes to Speak.

Now there are many tales told of that old man and his queer ways, for the most part having little truth to them. Facts seem to alter with the passing of time, when no one remembers the truth; and but one man now lives who attended that last banquet in the House of the Worm, and he is mad.

They say that he was not old when first he looked on the five pillars on the round hill overlooking Vornai in the plain of Kaar. He had held more contempt for the legends than fear, and had gone there alone to scoff at the daemons said to dwell within the ring. He went in the daylight, and would have returned long before dusk, for even his rash skepticism would not let him dare this thing by night. But the spell of the place caught him; or a morbid fascination of the way the monoliths shadows curiously distorted all they fell across; and how these shadows were cast not by sun or moon, but red Betelgeuse in the starry sky. Or perhaps he guessed the meaning of certain cryptic signs on the stones, or only stood too long in their presence. He did not return at dusk. Rather he came with the morning breeze when eastern skies were crimson. He came as one bowed beneath the weight of years; and the people wondered to see his raven locks turned white, and wondered more at the odd light that shone in his eyes, the light that would never leave him. They wondered, and only whispered, The daemons. He went slowly up to his cottage, speaking to no one, and was not seen again for a week and a day.

And the time passed quickly for the people of Vornai, and with it much of the amazement brought by the return of Him of Whom No One Likes to Speak. But on the eve of the ninth day a great and terrible Fear prowled in the citys shadowed lanes, entwining the spires and minarets of the palaces and temples in webs of horror, or sending forth icy tendrils to snare the minds and souls of the unwary. The ground beneath them muttered queerly, and unguessed evils rode the wind. And inside none dared sleep for fear of evil dreams; but crouched trembling in the dark behind locked doors, while taloned things scratched at shutters and laughed, and eldritch lights flashed from the top of the hill where the pillars stand, with none to see save that old man.

An in the morning he took up residence in that great House now standing betwixt the pillars, where no house had ever stood before.

This they were willing to tell me in the city when I came to the plain of Kaar where all men fear the shadow of that House. It was only of that other matter that they were reluctant to speak. For these events are still too clear in their minds, though half a century old, and such is the horror of the memory that at its merest mention they seal their lips and go to count their beads and mutter prayers to their curious pot-bellied golden gods. And this is strange, for only three persons attended that last banquet in the House of the Worm, and of these but one now lives. They told me of him in the city when they saw that I was determined to have the tale, and told me also that he was mad.

This greybeard, they said, had become a hermit, and had secreted his dwelling on the hill where the trees are thick and do not behave like trees; and now he spoke no more to men, but worshipped a curious fetish on nights when red Betelgeuse is obscured by clouds. But I found his cave by daylight when the stars cannot be seen; and he that spoke no more to men was at last persuaded to speak (with the aid of a skin of the heady red wine of Sarrub, whose like is not in the World), and then and there he told me this tale.