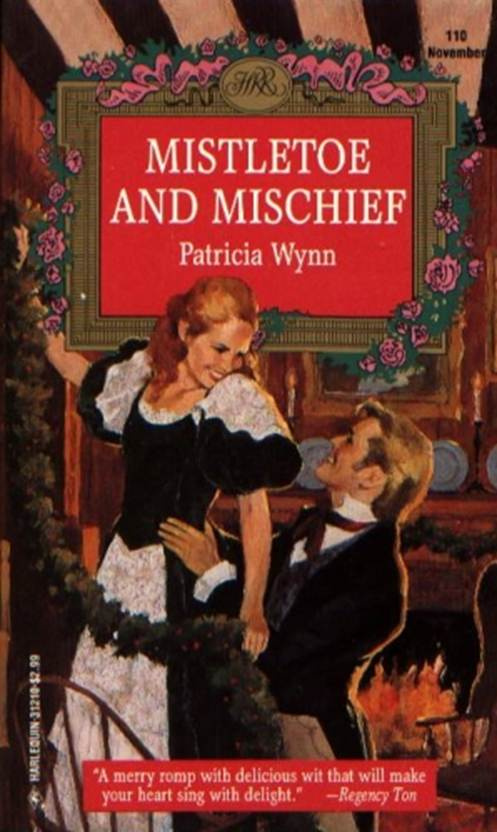

Patricia Wynn Ricks

Mistletoe and Mischief

Copyright 1993 by Patricia Wynn Ricks

Charles, Lord Wroxton, stood alone in the inn yard and looked about him in the vain hope that his private coach would appear.

A headache seemed poised just beyond the edge of his consciousness. He was tired of travelling, tired of staying at inns, and if the wheel to his carriage had not perversely broken in just this spot, he might at least have begged lodging for one night at the home of his colleague, Lord Northridge. It was with this objective in mind that he had chosen to take the western road back to London. Nothing else, he thought with a fleeting annoyance, could have persuaded him to pass through such a disreputable village as Gretna Green.

Only a few days remained before Christmas, but Charles, in his capacity as adviser to the prime minister, had been given a special dispatch to deliver to a Scottish government official, who had preceded him to Edinburgh. The Regent's fear of Napoleon's spies had led him to request that a gentleman of Charles's standing and unquestionable loyalty serve as messenger in this delicate matter.

Naturally, Charles had complied; but now he wished for nothing more than his own bed and hearth, a warm bowl of punch and a sound vehicle to take him away from the scene of so much foolishness.

While he had been standing in the yard, a series of equipages of all sorts and varieties had come and gone. One young couple had emerged from a post-chaise looking tired, rumpled and harried, but with an underlying sense of excitement. Another couple, married at great haste, had taken to their carriage just as a light snow had begun to fall. Their hired vehicle had sped off back towards the English border.

Watching them, Charles pressed his lips together in distaste. He devoutly hoped that no acquaintance of his would discover him in this Scottish town. Travellers to Gretna Green could only be here for one reason-to contract an ineligible marriage. If he recognized any of them, he would be obliged to try to dissuade them from carrying out such an ill-conceived start.

For the moment the yard was empty, and it seemed strangely forlorn. Charles had a sense, a flickering sense of being alone in a cold and bleak void.

Pssst!"

A hissing noise came from somewhere behind him. Charles turned his gaze towards the source of the intrusive sibilant.

A post-chaise and four stood at the ready near the stable, but no other carriages were in sight. As Charles looked about him, he thought he spied a young lady waving to him from behind the chaise. But before he could respond to her improper behaviour, a gentleman came quickly round the corner of the smithy across the lane, and the young lady-if so it was-vanished behind the carriage.

Confused by these sudden comings and goings, and half-blinded by the snow, Charles began to wonder if the whisper had issued from someone else.

He searched again, but heard nothing. Out the corner of his eye, Charles saw the young gentleman approaching, an anxious frown marring his rather florid features. The man threw a quick, nervous glance about the inn yard, and with a muttered curse hastened back to the smithy as if he had misplaced something important.

The curious display drew a reluctant chuckle from Charles. Apparently the young man had been kept waiting at the altar. The blacksmith who owned that shop was famous for the weddings he performed over his anvil. The business he derived from just such persons as this gentleman had turned him from his rightful profession-so much so that he had had the infernal impudence to keep Charles cooling his heels while he performed one ceremony after another. As Charles's coachman had reported it, the smith had said that there was more money to be made in weddin's than in mendin coaches, so his lordship'll just haf ta wait."

Only a few witnesses and a public declaration were needed for marriage to take place this side of the border-no announcements or banns and no parental consent to hamper the process. Consequently, many young couples who had been forbidden to wed flew to this village, the first one north of the River Sark, to plight their troth before their parents could be alerted to their disappearance and catch up with them. The blacksmith had found himself in a fine position to take advantage of such desperation. His fees were commensurate with the degree of haste required.

A gentleman who had been raised with the strictest of principles, as Charles had, could only be offended by such conduct. He stiffened as he watched the other man disappear behind the smithy. Charles had no intention of mixing with the sort of harum-scarum individuals so lost to propriety as to even contemplate a rash marriage. He glanced at his timepiece and wondered how much longer he would be made to wait while such goings-on took place.

Pssst! Oh, sir! Pssst!

The whisper again-and this time clearly from the young woman.

Certain now of the source of it, Charles decided to pretend he had not heard her. Since achieving his majority, he had often been accosted by women of dubious morals. A young man, regarded as handsome by most accepted standards could expect a certain amount of feminine attention. Even if his position were unknown, he knew that one sort of woman, at least, needed no more encouragement to approach him than the fact of his having a few shillings in his pocket. He would do better not to respond.

Oh, sir, please!"

The clear tone of her voice made a different impression on him this time, and Charles wondered if he might not be mistaken in his first assessment. The unwelcome thought that he might actually know the lady crossed his mind.

It was just possible. Aristocratic girls were no more immune to foolishness than any other sort. Perhaps, having given way to the importunities of a fortune-hunter, this young woman now stood in need of temporary pecuniary assistance. If she had recognized him, naturally she would apply to him.

He decided to look behind him, all the while praying for this not to be the case, and cursing the wheel that had caused him to stop this side of the border.

A quick glance showed him that the confounded chit was waving at him again. But with a swell of relief, he saw that he did not know her. He did not know anyone, thank God, with such an alarming shade of hair.

He turned away again without so much as acknowledging that she had spoken. He judged he would do better to leave the yard, as unpleasant and exorbitant as the accommodations at the inn were likely to be, until such time as his carriage would be ready and he could escape.

But Charles had taken no more than two steps away from the girl, when he heard her say to his back, Oh, pooh! If you mean to be so disagreeable, I suppose I'll have to try someone else!"

He paused.

Charles Beckworth, Marquess of Wroxton, 4th Earl of Sandbach, and 12th Baron Beckworth, had been accosted by bold women many times. In Bath, where he kept a house, and in London, the story was the same. Women, dressed as ladies and primed for their trade by stern madams, did their utmost to attract the attentions of wealthy customers.

But in all his encounters with such persons, not one of them had ever said Pooh! to him.

Charles turned again and saw that the young woman was regarding him with reproach. She clutched her reticule before her, and she held her chin high in the air.

Run along, she said, tossing her red-gold curls as if the very sight of him offended her. If you have no mind to assist a lady, then I do not want you about. Run along, then! Go!"

As a marquess, Charles was not accustomed to taking orders from anyone. And in peacetime, he had reflected more than once, he might seriously question orders from the Regent himself. Even so, only a few moments ago, he might have obeyed the young lady, and gladly. But by now he had taken the time to examine her more closely, and his temper had undergone a change.

Next page