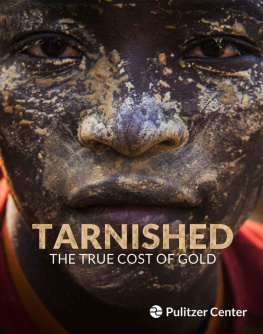

Tarnished

Table of Contents

How To Read This Book

Tap or swipe on edges of the screen tomove through the book.

Tap center of screen to bring up the book menu. Click "GoTo" to navigate to a different chapter in the book.

Press and hold on book text and images make notes, search thebook or highlight text.

Double tap images to enlarge them to full screen. Spread yourfingers on the screen to zoom in. Press the "X" in thetop right corner to go back to the text.

You can change the size of the text, margins and spacing tofit your reading style by tapping the center of the screen andclicking "settings." We recommend font size 4, normalline spacing and narrow margins.

Introduction

Over the past four years, as the price ofgold surged and fell, the Pulitzer Center has commissioned eightprojects on what the boom has meant for local communities involved.The reporting covers the globe and the stories that resulted haveappeared on our website and in major media outlets, from TheNew York Times and PBSNewsHour toHarpers, The Philadelphia Inquirer andTIME. Now we are pleased to present in e-Book form asampler from that work, organized by key themes and drawing on thewriting, photographs, and video that have made this journalism socompelling.

Tarnished takes you behind the scenes to show how thatglittering piece of jewelry came to be, in settings far removedfrom Madison Avenue or Rodeo Drive or your local mall. Youllwitness Peruvian miners using their bare feet to mix toxic mercuryinto barrels of gold-bearing sediment. Youll see the gnarled handsand callused feet of boy miners in Burkina Faso, old before theirtime. Youll experience what its like, in the forests of Panama oralong the coast in Turkey, to choose between desperately neededjobs and the protection of land and traditional cultures that couldbe lost forever.

Some of these stories are harrowing and sad but there is alsomuch that inspiresfrom two feisty women mayors in small-townBulgaria taking on multinational mining companies to the spread offair-trade mining in southern Peru and growing support for theefforts of groups like the International Labour Organization todevelop standards and get them enforced. We hope the readers ofTarnished will come away with the realization that when it comesto gold the metal itself may be untarnished but the mining anddistribution are not. Everyone of us is involved, as consumers andcitizens. Whether this unique resource is produced in a way that isfair to all is very much up to us.

The reporting behind Tarnished was made possible by supportfrom the Wallace Global Fund, the Kendeda Fund, Humanity United,and individual donors. The e-book was edited by Kem Knapp Sawyerand designed by Meghan Dhaliwal. The Pulitzer Centers series ofe-books are intended to take our journalism to new audiences, inthe educational community and beyond. We also hope to generate newsources of income for the journalists who do the work that makespossible projects like Tarnished.

Jon Sawyer

Executive Director

Chapter 1: A Family Affair

While investigating gold mining inBurkina Faso photojournalist Larry C. Price traveled to the Kollomining village where he saw young childrenone four years old andbarefoothauling buckets of water, smashing boulders, andsharpening metal-grinding wheels. In the Philippines he met youngboys who worked underwater in deep pits on the island ofMasbatebreathing through slender tubes attached to compressors.Mining has become a family affair.

In both countries child labor is against the law, but Pricetells us these laws are rarely enforced. In Burkina Faso 30 to 50percent of small-scale miners are children. In the Philippinesthere are more than 18,000 children who work in the mines. Thesechildren risk injury, death, drowning, and a plethora of healthconsequences, including lung and neurological damage, due toexposure to dust, mercury, and other toxic chemicals.

In writing about child labor in Burkino Faso and thePhilippines, Price brings us face to face with some of the youngminers in both countries, focusing on the physical risks tochildren. He reminds us there is no easy solution. The wages minersreceive are so low that many families are dependent on theirchildren for income.

The Cost of Gold in Burkina Faso

Larry C. Price

A Gold Mine Is Born

Almost at once, the people arrive, hundreds of them, men, womenand children, assembling in the shimmering twilight by the roadsidein the Burkina Faso countryside. They have come many miles andtraveled for days, by foot, bicycle, bus, scooter and lorry, drawnto this rocky, arid stretch of land near the Ghana border by therumor of gold.

Men with muscular arms and calloused hands that attest to theirexperience in the gold fields survey the land and, with just a fewgestures, pronounce it fit to explore. The people pitch camps orlie down to sleep in the dirt by the road, ready to rise at dawnand begin prospecting.

Short hours after sunrise, with cooking smoke still hanging inthe air, the land is raked bare of its sparse grasses and rid ofits spindly trees. The digging begins. All hands, even the tiniestones, are in the dirt, frantically clawing rocks into buckets,bowls and pans.

And just like that, a small-scale mine is born.

Burkina Faso has rich gold deposits that until recent times havegone untapped. Unlike its neighbors, Mali and Ghana, that builtancient empires on the gold trade between Africa and Asia andremain major producers today, Burkina Faso is a relative newcomerto the world gold market. Major foreign mining companies have onlyrecently returned to the country after being banned in the 1990s.Small-scale gold mining began in the 1980s, as families, forcedfrom their farms by drought and famine, literally began trying toscrape a living from the ground.

Today, Burkina Faso, ranks 4th in Africa and 23rd in the worldin gold production. Only modestly regulated, small-scale minesspring up overnight wherever gold is rumored to be. If the goldfield is on municipal land, local authorities will tax eachproducer 10,000 CFA or about $20 a year. If the gold field is onprivate land, the landowner may work an arrangement for a share ofthe proceeds.

If a gold field is good, word gets out and a boomtown springs upwith shanties, supply huts, restaurants and assorted kiosks amongthe hastily constructed tarp dwellings. If the gold holds out, anew village will grow. There will be roads, water wells andeventually generators for electricity.

Small-scale gold mining in Burkina Faso, as in other developingcountries, is a family affair. Even the youngest children workalongside their parents or in small groups. In a 2006 report theInternational Labour Organization (ILO) estimated that 30 to 50percent of the people working in small-scale mines in the AfricanSahel, which includes Burkina Faso, are younger than 18.

At this barren place near the settlement of Bilbal, about 20kilometers east of Dibougou, there are probably 50 children amongthe 200 people working. Mothers with babies on their backs benddouble from the waist to rake rocks into buckets, coveringthemselves and their infants with thick red dust. Naked toddlersplay near their mothers while bare-bottomed boys, no more than 3 or4 years old, hack at the ground with primitive, handmade hoes thatare longer than they are tall. All of the children and many of theadults are barefoot.

Four-year-old RasmataOuedraogo, left, and another child sort pans of soil for sifting.Image by Larry C. Price. Burkina Faso,2013.

Four-year-old RasmataOuedraogo, left, and another child sort pans of soil for sifting.Image by Larry C. Price. Burkina Faso,2013.

Four-year-old RasmataOuedraogo, left, and another child sort pans of soil for sifting.Image by Larry C. Price. Burkina Faso,2013.