Training for the

NEW

ALPINISM

Training for the

NEW

ALPINISM

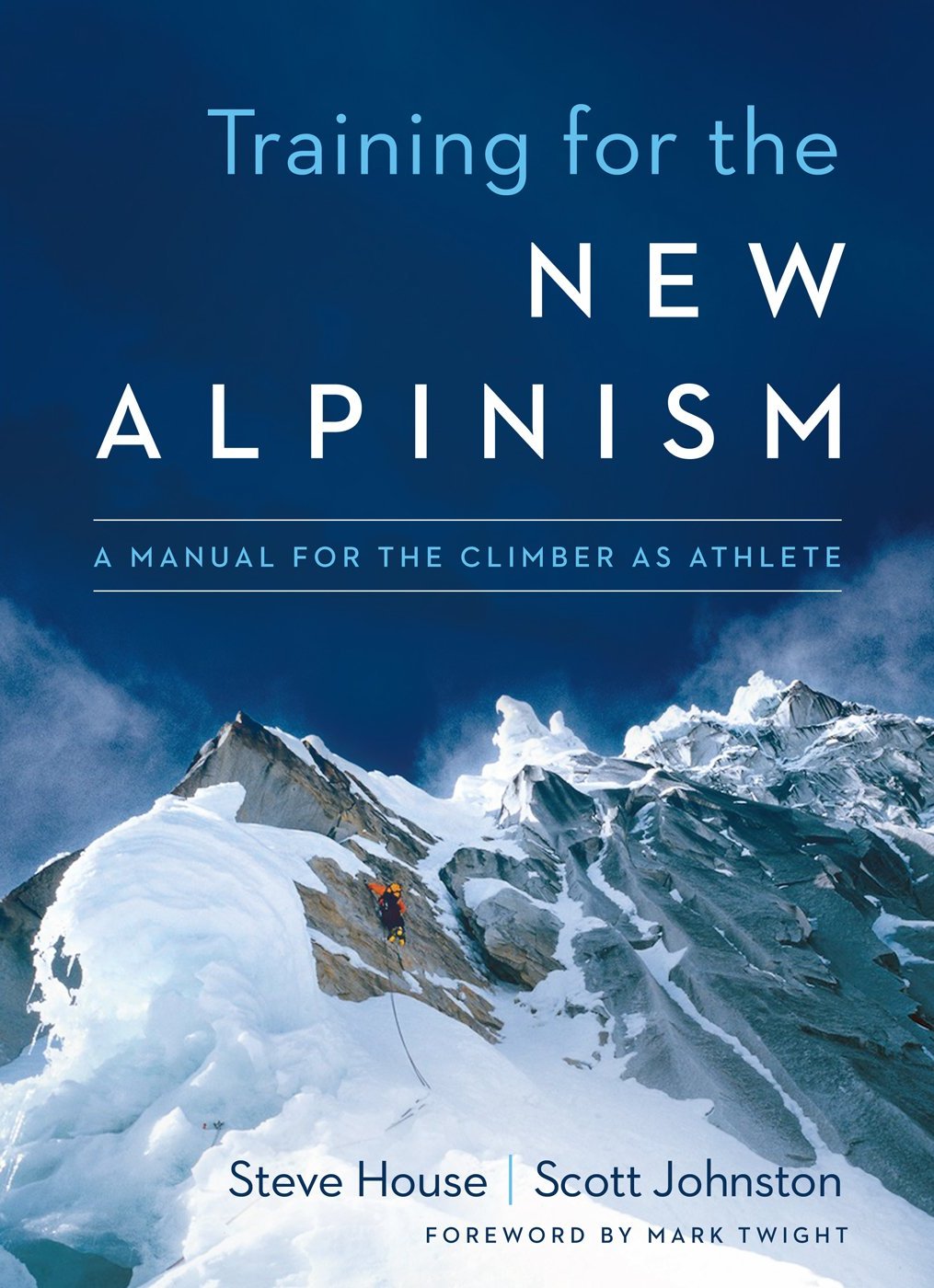

A MANUAL FOR THE CLIMBER AS ATHLETE

Steve House and Scott Johnston

Contents

Mark Twight exiting the Col Fourche bivouac near Mont Maudit, France. Photo: Ace Kvale

Foreword

The Edge of the Map

I consider myself a charter member of the first generation of alpine climbers who trained intentionally using artificial means.

For me, training was born of failure. When I failedand it happened a lotit was because ambition outstripped ability. I narrowed that lack of ability to physical issues often enough that I decided to do something about it. Chasing the first half of Brian Enos motto, I pushed myself to the most extreme limits and reaped rewards, but it took years to fulfill the second half of that motto, which is retreat to a more useful position.

My approach to training echoed how I climbed. The romance of climbing didnt interest me. I didnt seek harps and wings. I heard no opera up there. Instead, my mountains had teeth. The jagged edge we walked up there dragged itself across my throat, and the throats of my friends and peers. I took the mountains indifference to life as aggression, and fought back. I armored myself against that indifference; with training, with thinking, with attitude. I trained with friends who shared a similar approach. Our mantra was dark, but it motivated us.

When we ran we breathed in rhythmno matter the speedand that beat had words: They all died. We inhaled and exhaled the great alpine epicslike the tragedy that befell Walter Bonattis party on the Freney Pillarto push ourselves to a place where we would never come up short, physically.

The consequences of falling short made training important. I realized early that controlling the things that I could control gave me greater freedom to address the things that I could not control. And the mountains offered those in spades.

Unfortunately, I had no idea how to use the gym, and without someone to ask, I made many mistakes. I tried to mimic climbing in the weight room, but didnt comprehend how best to use this valuable tool, and wasted my time. The gym is useful as a means of overloading the organism in a way that cant (safely) be done in the real environment of alpinism.

Later, my training sessions began by pre-fatiguing my body on a Stairmaster, or treadmill, and then lifting because thats how alpinism looked to me: approach and then climb. It took years to learn that doing the opposite sent hormonal signals more appropriate to physical development for alpine climbing.

Then I read that some rock climbers used hypertrophy-style training to increase muscle mass and push limit-strength higher. So we did that until I realized that mass had to be carried whether it was being used or not. I had misused a specific training idea based on the mistaken premise that all climbing is the same. It isnt. Limit-strength was never an issue in the mountains but we wanted it to be, so that we could do that style of training.

Eventually I trained in a way that emphasized maximum recruitment of existing muscle. I had to carry my own engine so it made sense to increase my power-to-weight ratio; to extract the maximum from existing resources. Then, I reasoned, if the engine is still inadequate, I could increase its horsepoweras long as that doesnt affect fuel economy.

The engine analogy produced an accurate description of our training objectives, which allowed us to think and plan in coherent terms. We decided that the ideal engine for alpinism could go forever, produce explosive force on demand and keep delivering 50 to 60 percent of peak force without overheating. Tuning such diverse characteristics into an engine requires much of the mechanic, foremost of which is an understanding of the overall objectives.

In Extreme Alpinism: Climbing Light, Fast and High, I described the goal of physical training for alpinism with the phrase to make yourself as indestructible as possible. In short: resilience. For too long I thought this concept was solely contingent on physical capacities, but eventually realized that these influence mental capacities. In fact, I think we revere the physical too much when it is the mind that imagines the goal, solves the problem, and achieves itusing the body as its engine.

Mark Twight climbing the Chere Couloir, Mont Blanc du Tacul (13,937, 4,248m), France in 1990.

Photo: Ace Kvale

If physical training is a tool, its a hammer. Often we swing it to the exclusion of all other tools because it feels like an easy fix: it features nearly immediate positive feedback as well as rapid progress, especially if youve never used one before. But increased physical capacity doesnt guarantee improvements to climbing. Often strength blinds us to the benefits of technique or efficiency. We close our eyes and pull, but alpinism rarely rewards raw strengthsuccessful alpinists appear to be those who multiply physical force with the lever of creativity, confidence, and psychological resilience.

Undertaken correctly, physical training is a useful means of psychological manipulation: goals set, achieved, and surpassed in the gymwhether they are specifically transferable or notstimulate psychological development we can express in the mountains. Constantly overcoming difficult training challenges and examining ourselves along the way improves self-assurance. That confidence frees imagination. It opens doors to new, more difficult projects, and expands our problem-solving repertoire.

To attempt the impossible demands a high order explosion of confidence, sustained by the diesel-fueled physical capacity to back up that hubris. Neither capacity is powerful on its own but a whole, well-trained mental-physical system is practically unstoppable. In this sense we can bring our unrealistic ambitions within reach by figuratively changing the length, and functionally increasing the strength of our arms.

The really big routes I climbed didnt happen because I trained harder. Rather they happened as result of having trained better and climbed more. Frequency and consistency and accumulation allowed me to go harder, higher, and for longer. Increasing the intensity of the artificial training was never critical. Intensity played a minor role: it could not shortcut experience or efficiency. Twenty years of consistent training squeezed wretched mental weakness out of me and built a vast foundation of accumulated fitness. The resulting deep physical tank and huge psychological reserve opened up terrain and timing that I could never have imagined without it. Training was one of the keys to my success as a climber, but not in the way I believed it would be when I hit the weight room that first time.

Mark Twight and Scott Backes approaching the south face of Denali and the Slovak Direct Route.

Photo: Steve House

These days physical and mental training is my bread and butter. Strength training directly benefits the athlete who plays a sport in which the strongest always wins. Thats not climbing. So we work indirectly: When we increase an athletes work capacity, we improve that persons ability to recover, then climbing-specific training frequency can be increased, which means more climbing. A greater volume of quality sport-specific effort leads to improvement. This is training but it is also lifestyle, and managing it wholesale.