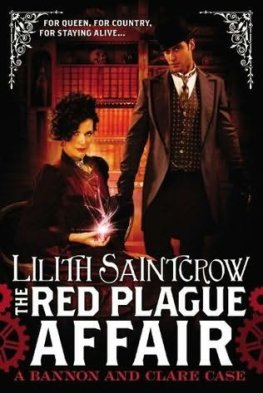

The Iron Wyrm Affair

(The first book in the Bannon and Clare series)

A novel by Lilith Saintcrow

For those who serve in shadow

Thanks are due to the long list of the Usual Suspects: Miriam and Devi, for believing in my crazed little stories; my children for understanding why I hunch over typing for long periods of time; Mel for gently keeping me sane; Christa and Sixten for love and coffee. Thanks are also due to Lee Jackson for his love of Victoriana, and to Susan Barnes (soon to be a Usual Suspect) for putting up with me. And finally, as always, once again I will thank you, my Readers, in the way we both like best. Sit back, relax, and let me tell you a story

it is not required to possess a mentaths faculties in order to Observe, and to reap the benefits of said observation. Indeed, many mentaths are singularly unconcerned with any event or thing outside their chosen field of study, while a rich treasure trove of wondrous variety unreels before their very noses. A mere observer skilled in the science of Deduction may surprise even a mentath, and has the added benefit of a great deal of practical knowledge and foresight ever at hand. The faculty of Observation lies within each man competent enough, and taught to, read; it may be strengthened with practice, and indeed grows ever stronger the more one exercizes it.

If Observation is the foundation all Deduction is built upon, then the quality of Decision is the mortar holding fast the stones. Tiny details may be important, but it is of greatest necessitude to decide which details bear weight and which are chaff. Perfect, unclouded decision upon details is the purview of the Divine, and mans angelic faculties, wonderful as they are, are merely a wretched imitation. Even that wretchedness can be useful, much as the example of Vices ultimate end may serve to keep Virtue from the wide and easy path to Ruin.

Much as Time seeks to bring down every building, and Vice seeks to bring down every Virtue, the treacherous Assumption ever seeks to intrude a details importance wrongly into Deduction. A proper Assumption may save a great deal of time and trouble, but an improper Assumption is a foul stinking beast, ever ready to founder the ship of Logic upon the rocks of Inaccuracy.

Fortunately, the weapons of Reason and Observation do much to overthrow the false faces of Assumption. The decision to carefully and thoroughly question each Assumption as if it is a criminal, or a fool who does not differentiate Fact from Fancy, will serve each person seeking to strengthen his habit of Deduction faithfully. As the organs of Reason and Observation strengthen, the art of quickly finding the correct details becomes natural.

We shall start with a series of Exercizes to strengthen the faculty of Observation any Reader assaying this humble work possesses. These Exercizes are to be done daily, upon waking and retiring, and at diverse points through the Readers daily work as opportunity permits

From the Preface, The Art and Science of Deduction, Mr Archibald Clare

Prelude

A Promise of Diversion

When the young dark-haired woman stepped into his parlour, Archibald Clare was only mildly intrigued. Her companion was of more immediate interest, a tall man in a close-fitting velvet jacket, moving with a grace that bespoke some experience with physical mayhem. The way he carried himself, lightly and easily, with a clean economy of movement not to mention the way his eyes roved in controlled arcs all but shouted danger. He was hatless, too, and wore curious boots.

The chain of deduction led Clare in an extraordinary direction, and he cast another glance at the woman to verify it.

Yes. Of no more than middle height, and slight, she was in very dark green. Fine cloth, a trifle antiquated, though the sleeves were close as fashion now dictated, and her bonnet perched just so on brown curls, its brim small enough that it would not interfere with her side vision. However, her skirts were divided, her boots serviceable instead of decorative though of just as fine a quality as the mans and her jewellery was eccentric, to say the least. Emerald drops worth a fortune at her ears, and the necklace was an amber cabochon large enough to be a baleful eye. Two rings on gloved hands, one with a dull unprecious black stone and the other a star sapphire a royal family might have envied.

The man had a lean face to match the rest of him, strange yellow eyes, and tidy dark hair still dewed with crystal droplets from the light rain falling over Londinium tonight. The moisture, however, did not cling to her. One more piece of evidence, and Clare did not much like where it led.

He set the viola and its bow down, nudging aside a stack of paper with careful precision, and waited for the opening gambit. As he had suspected, she spoke.

Good evening, sir. You are Dr Archibald Clare. Distinguished author of The Art and Science of Observation. She paused. Aristocratic nose, firm mouth, very decided for such a childlike face. Bachelor. And very-recently-unregistered mentath.

Sorceress. Clare steepled his fingers under his very long, very sensitive nose. Her toilette favoured musk, of course, for a brunette. Still, the scent was not common, and it held an edge of something acrid that should have been troublesome instead of strangely pleasing. And a Shield. I would invite you to sit, but I hardly think you will.

A slight smile; her chin lifted. She did not give her name, as if she expected him to suspect it. Her curls, if they were not natural, were very close. There was a slight bit of untidiness to them some recent exertion, perhaps? Since there is no seat available, sir, I am to take that as one of your deductions?

Even the hassock had a pile of papers and books stacked terrifyingly high. He had been researching, of course. The intersections between musical scale and the behaviour of certain tiny animals. It was the intervals, perhaps. Each note held its own space. He was seeking to determine which set of spaces would make the insects (and later, other things) possibly

Clare waved one pale, long-fingered hand. Emotion was threatening, prickling at his throat. With a certain rational annoyance he labelled it as fear, and dismissed it. There was very little chance she meant him harm. The man was a larger question, but if she meant him no harm, the man certainly did not. If you like. Speak quickly, I am occupied.

She cast one eloquent glance over the room. If not for the efforts of the landlady, Mrs Ginn, dirty dishes would have been stacked on every horizontal surface. As it was, his quarters were cluttered with a full set of alembics and burners, glass jars of various substances, shallow dishes for knocking his pipe clean. The tabac smoke blunted the damned sensitivity in his nose just enough, and he wished for his pipe. The acridity in her scent was becoming more marked, and very definitely not unpleasant.

The rooms disorder even threatened the grate, the mantel above it groaning under a weight of books and handwritten journals stacked every which way.

The sorceress, finishing her unhurried investigation, next examined him from tip to toe. He was in his dressing gown, and his pipe had long since grown cold. His feet were in the rubbed-bare slippers, and if it had not been past the hour of reasonable entertaining he might have been vaguely uncomfortable at the idea of a lady seeing him in such disrepair. Red-eyed, his hair mussed, and unshaven, he was in no condition to receive company.

He was, in fact, the picture of a mentath about to implode from boredom. If she knew some of the circumstances behind his recent ill luck, she would guess he was closer to imploding and fusing his faculties into unworkable porridge than was advisable, comfortable or even sane.