Prologue

Remembrance of Beers Past

If memory serves me right, the first beer I ever had was a Budweiser, clandestinely chugged on a half-street in South Brooklyn with a few other underage punks. It was the first of many. Eventually, I outgrew the bad judgment of youthat least most of itand learned to love good beer, consumed in moderation, in a state of relaxation.

Growing up and going to college in the Northeast/mid-Atlantic, great beer was abundant.

The industry-leading brews of the Brooklyn Brewery were everywhere, and I still remember the first time I tasted Dogfish Head 90 Minute IPA. Needless to say, I quickly learned there were things possible with beer that I had never understood before.

A few years later, my fixation on great beer was apparent and so both my girlfriend and sister pooled a few handfuls of disposable income to get me a birthday present: a 90-second shopping spree at Bierkraftthe best beer shop in Brooklyn. I remember it like yesterday; it was a Sunday morning and I arrived at the shop fifteen minutes before it properly opened. I filled a shopping cart with whatever labels grabbed my eye from its vast selection. It was spring, and the store manager complimented me for grabbing the seasonal Fantome, even though at the time I had never heard of how good (and rare) it was. I just liked the ghost on the label.

As my respect for beer and other alcoholic beverages continued to grow, I made my first home brew while living on eastern Long Island. I was ditching the New York City office grind to follow my passion: working as an assistant winemaker at a winery producing top-flight terroir -driven red, white, sparkling and fortified wines.

It was easy to indulge in my passion for great beer while working as a winemaker. In fact, we kept a tapped kegerator at work wedged between wine tanks numbers six and seven. Besides, a cold 20-oz. glass of quality IPA made the monotonous and dirty task of hosing down the winery floor at the end of every day a favorable task.

My urge to start making home-brew beer came at an inconvenient time. Our company was on the verge of an intense seven-week harvest. Despite the laborious efforts awaiting me at the winery, I had a mysterious instinct to drive an hour away to Northport, Long Island, on the last Sunday I would have off. I left Karps Home brew Supply with a TrueBrew equipment kit and a shopkeeper-approved Pale Ale ingredient kit. This was going to be awesome!

As I got back home, I excitedly unpacked the gear and, of course, broke the hydrometer. The next dayLabor DayI made an unscheduled drive to work to borrow a hydrometer from the winery lab and quickly headed back home to start brewing.

As my first-ever wort took shape, I sanitized my gear with an overly strong bleach solutiona functional but inefficient way of getting the troops ready for battle. An hour later, per the instructions, the boil was over. Having not done any research on why cooling wort quickly is important, I let it sit for hours before sprinkling in the packet of dried yeast. I later learned what a bad idea this was, but somehow got away with it this time.

The next day, it was alive! When I saw it bubbling for the first time, and watched the living yeasts burbling and throwing the hops around the caramel-colored suspension, I knew there was no turning back. Making wine in big tanks was funeven though it was work but making beer in a little container where I could get constant visual, auditory and aromatic feedback from the burble and fizz was a different level of awesome.

Over the next week, I took too many hydrometer readings and tasted the beer too many times, increasingly excited at how good it was turning out. When I jumped the gun and bottled it after ten days, and then tasted the first bottle five days after that, I had the reaction most home brewers have the first time they get high on their own supply Wow, this is amazing, and I made it!

Two weeks later, despite being stuck in the relentless 70-hour workweeks of harvest season, I returned to Karps and bought a kit for a Marzen/Oktoberfest with ale yeast. Two weeks after that, I was back for an English-style IPA kit. I was hooked. From then on, no matter how purple my hands were from grape juice, I always found time to home brew.

As luck would have it, I had a very unique experience while working at the winery. Unbeknownst to me when I moved out to Long Island from NYC, the renowned Southampton brewmaster, Phil Markowski, had an arrangement with our winery to bottle their large-format beers on the winerys champagne packaging equipment.

Since Southampton did not have a champagne corker and our winery did, they would visit once or twice a year to bottle. The best part of the deal was when they would kindly leave a pony keg behind for safekeeping. One December day when Markowski and his crew came by to bottle, I was ready with two bottles of my very own chilled IPA. I was a little nervous to offer the drinks and request feedback because Markowski was renowned for his interpretations of Belgian and French farmhouse-style ales and Altbier and English-style IPAs. His beers had won 22 medals at the Great American Beer Festival, also known as the Oscars of professional craft brewing.

On the other hand, I was confident. I thought my beer was great.

Markowski politely sniffed and sippedI have to assume it wasnt the first time an eager home brewer had pushed an unlabeled bottle into his hand. I was hoping for unequivocal confirmation that I was destined for greatness as a brewer, perhaps accompanied by an on-the-spot job offer that would start a bidding war between the brewmaster and my winery boss that would escalate until I was the highest-paid tank-scrubbing assistant in America.

That remained a fantasy. But he was very cool and helpful, asking pointed questions about my recipe that illuminated a lot of cause-and-effect links that serve me well to this day. Most of all, he recommended that I use liquid yeast instead of dry yeast whenever possible. I wasnt even aware liquid yeast existed.

So I went forward. The wine grape harvest ended, and with the extra time available, I brewed even more. In fact, Ive brewed ever since. Despite a few dark months of very stupidly brewing without detailed records, I can look back on countless home-brewing sessions and chart the steady improvement and understanding of the process.

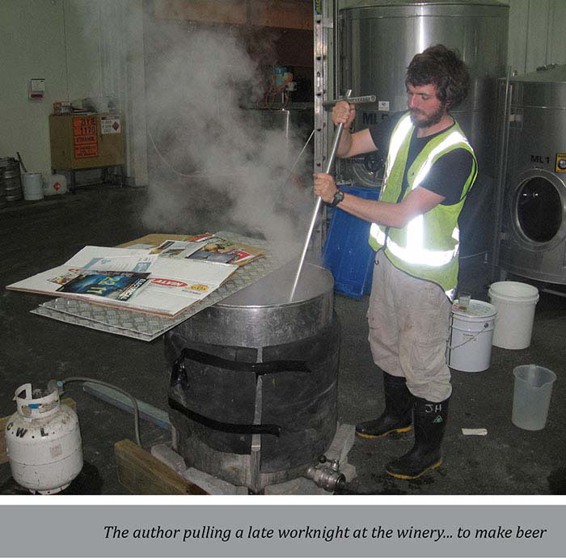

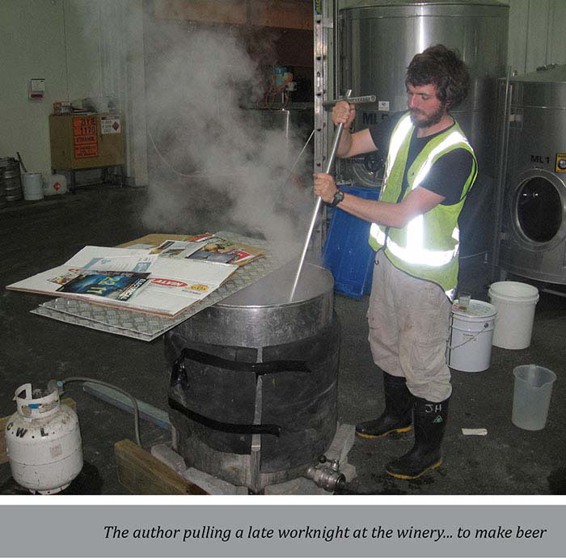

My largest brew to date was almost forty gallons. I was seasonally employed at a winery in New Zealand in early 2010, where, despite the colossal size of the production facility, the thirst for quality after-work beer was just as strong as it was at my little winery back home. This one, located in an industrial section of the city of Napier, was a huge, corporate-owned operation. And in the shadows of its skyscraping mega tanks were many small sumps and tanks, some of them old and bound for the junk heap.