The Complexity of Greatness

The Complexity

of Greatness

Beyond Talent or Practice

Edited by Scott Barry Kaufman

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.

It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship,

and education by publishing worldwide.

Oxford New York

Auckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong Karachi

Kuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City Nairobi

New Delhi Shanghai Taipei Toronto

With offices in

Argentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France Greece

Guatemala Hungary Italy Japan Poland Portugal Singapore

South Korea Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine Vietnam

Oxford is a registered trademark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other

countries.

Published in the United States of America by

Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016

Oxford University Press 2013

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a

retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior

permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law,

by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization.

Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights

Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form

and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

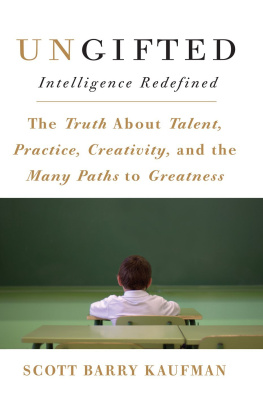

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The complexity of greatness : beyond talent or practice / edited by Scott Barry Kaufman.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 9780199794003

1. Ability. 2. Gifted persons. 3. Intelligence levels. I. Kaufman, Scott Barry, 1979

BF431.C596 2013

153.98dc23

2012040833

This book is dedicated to the fond memory of pioneering psychologist Michael Howean inspiration to many, and a fi ne example of greatness.

CONTENTS

Scott Barry Kaufman

Wendy Johnson

Dean Keith Simonton

Samuel D. Mandelman and Elena L. Grigorenko

Heiner Rindermann, Stephen J. Ceci, and Wendy M. Williams

James C. Kaufman, John Baer, and Lauren E. Skidmore

Martha J. Morelock

Darold A. Treffert

Paul A. OKeefe

K. Anders Ericsson, Roy W. Roring, and Kiruthiga Nandagopal

Franoys Gagn

K. Anders Ericsson

Gregory Feist

Linda E. Brody

John Wilding

Tony Noice and Helga Noice

Ellen Winner and Jennifer E. Drake

Jane Davidson and Robert Faulkner

Paul R. Ford, Nicola J. Hodges, and A. Mark Williams

Jane Davidson, John Sloboda, and Stephen Ceci

PREFACE

What is greatness and how do people get there? Is greatness born or made? Is greatness the result of talent or practice? Few other questions have caused such intense debate, controversy, and diversity of opinions. The heights of human accomplishment have always fascinated us, and for good reason. The striving for greatness is a fundamental human drive, and without it we would be bereft of some of our most valuable cultural products. How we conceptualize greatness and its developmental trajectory has important implications for education, business, and societywhich makes it all the more important that we make an effort to understand all the many complex, nuanced factors contributing to its emergence.

Greatness eludes precise definition, and historically it has been approached in different ways. In ancient times, greatness had spiritual connotations, and geniuses were viewed as divine. Kant thought talent was an integral ingredient of the emergence of greatness, as geniuses use their natural talents to produce something original and exemplary ().

Since the beginnxing of this debate, both extremes have been represented. Sir Joshua Reynolds, an influential 18th century British painter, warned his students at the Royal Academy that

You must have no dependence on your genius. If you have great talents, industry will improve them; if you have but moderate abilities, industry will supply their deficiency. Nothing is denied to well directed labour; nothing is to be obtained without it. Not to enter into metaphysical discussions on the nature or essence of genius, I will venture to assert, that assiduity unabated by difficulty, and a disposition eagerly directed to the object of its pursuit, will produce effects similar to those which some call the result of natural powers. ()

While it seemed everyone had an opinion, the topic started receiving scientific treatment with the publication of Francis Galtons Hereditary Genius in 1869. Based on his analysis of eminent lineages, Galton, who was Charles Darwins cousin and was greatly influenced by Darwins ideas, argued that genius is primarily born. While Galton acknowledged the importance of passion, zeal, and persistence, he argued that regardless of environment, those with exemplary natural abilities inevitably rise to the top (showed evidence for the importance of environmental factors, finding that eminent scientists from Western civilization tended to do their best work under particular political, economic, social, cultural, and religious circumstances. However, while de Candolles results showed the importance of environmental conditions on the average population, his data did little to explain individual differences within a population.

The early behaviorists, including B. F. Skinner and John Watson, emphasized conditioning. No doubt biased by his particular theoretical position on learning and behavior, Watson made the following bold claim:

Give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in, and Ill guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might selecta doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant-chief, and yes, even a beggar-man and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations and race of his ancestors. I am going beyond my facts and I admit it, but so have the advocates of the contrary and they have been doing it for many thousands of years. ()

Regardless of the veracity of this bold assertion, at least Watson was honest that more data were needed on this topic! The advent of cognitive psychology brought an emphasis on expertise acquisition as the main factor underlying differences in elite performance. Nobel Prize laureate Herbert Simon and William Chase suggested that a decade of intense work and apprenticeship is required to become an expert in chess ().

While deliberate practice is certainly important, its unlikely to be the whole story. Even though the most cited and well-known philosophers and psychologists of all time were those who took extreme views on key debates of their time, including the naturenurture debate, more moderate, integrative stances are more likely to be correct (). Things are often not what they seem.

Take the practice side of the debate. Many studies looking at experts suffer from a restricted range: Those without the requisite abilities have already been weeded out of the competition, so those skills will no longer be predictive of performance. What happens when you look at a random selection of the population? While deliberate practice may be an important contributor to expertise, is it also sufficient to carry just anyone all the way to greatness? Dont some people invent a whole new path of deliberate practice for others to follow?