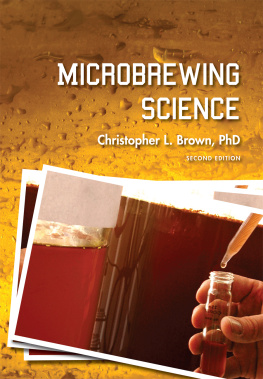

Microbrewing

Science

Christopher L. Brown, PhD

Second Edition

With Photographs By Michael H. Upright

Illustrations And Cover Photograph

By Shannon B. Brown

Bassim Hamadeh, CEO and Publisher

Christopher Foster, General Vice President

Michael Simpson, Vice President of Acquisitions

Jessica Knott, Managing Editor

Kevin Fahey, Cognella Marketing Manager

Copyright 2013 University Readers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information retrieval system without the written permission of University Readers, Inc.

First published in the United States of America in 2012 by University Readers, Inc.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Printed in the United States of America

ISBN: 978-1-62131-295-6

Preface to the Second Edition

T he purpose of this volume is to present an organized program of instruction focusing on the basic skills and problem-solving abilities necessary to brew classic styles of beer. You can think of this as a book about yeast aquaculture. The need for a book of this sort became apparent during several years of a multidisciplinary, upper-division university course in Brewing Science. Numerous excellent texts and journals on brewing technology are available, but we did not find one that laid out a methodical series of activities designed to help the aspiring brewer build a working knowledge base. Many are encyclopedic, presenting a distracting overview of all of the options available to a brewer. It was like studying haiku and assigning the Oxford English Dictionary as required reading. Our course was conducted initially with required readings from a range of sources, demonstrations, tours, and a set of laboratory exercises intended to piece together a background for the production of traditional microbrews. There was also the occasional pub crawl. Our approach was always a selective onehere is what you need to get started on a classic track. Later, we used the first edition of this text supplemented with an assortment of other readings and laboratory exercises. At times we also partook in the occasional pub crawl.

Several themes occur regularly throughout this text. First, brewing is a form of aquaculturethe careful management of a variety of physical and chemical parameters for the cultivation of aquatic organisms. Working with yeasts is not entirely different from the propagation of rotifers or the rearing of delicate, microscopic, newly-hatched fish larvae. Yeasts that thrive because they are well-fed and in an optimized environment can make a spectacular ale, and it is possible to manage and master the variables to make a variety of excellent ales and beers. Our goal is to help you build the knowledge-base needed to make an assortment of classic ales and lagers. We thank Anheuser Busch for a generous grant that helped to equip our Brewing Science laboratory. Most of our students made significant progress toward this goal within a single, rather memorable semester. Secondly, thorough note-taking is an indispensable part of the learning process. Novices make mistakes, and those can be reduced or eliminated by persistently recording events with plenty of attention to detail. Specific gravity and dissolved oxygen content are languages that the competent brewer must learn to speak. Equipment-wise, it is entirely possible to become an accomplished brewer without heavy investment in a brewery. We present and evaluate options for the brewing student, ranging from improvisational hobbyist gear like plastic buckets to far more elaborate and expensive contraptions. We even consider tricked-out devices with valves and gauges, for those of us that get endorphin rushes from messing about with such things. Finally, several of the shortcuts and mistakes that can convert a batch of beer into a complete catastrophe are laid out. Many of these are avoidable problemsthings that seldom happen to a brewer that knows what to watch out for, which is especially true for one who understands how contaminating bacteria can ruin an otherwise beautiful brew. Respectable brewing takes attentiveness to sanitation, a feel for the wellbeing of yeasts, and the ability to avoid repeating mistakes.

Introduction

T he theoretical and scientific basis for brewing can be overwhelming, and it may seem at first that only a biochemist that sometimes goes on NPR could be competent at making good beer. To a beginner, the choreographed additions of measured ingredients to various stainless steel vessels, and the elaborate changes that occur during boiling and fermentation give the impression that improvisation could never work, and that attempting to do so would guarantee disastrous results. Encyclopedic brewing texts may not be as helpful as their publishers want you to believe they are, and may leave you thinking that brewing is a complex task with far too many barely comprehensible variables. Commercial brewery tours can be equally intimidating; the sight of brewers using huge vats, automated valves, electronic gauges, and instruments can promote the idea that brewing should be left only to those that wear professionally-embroidered lab coats.

But it is not so!

One can develop a sound knowledge base and a good deal of confidence through practice, skill-building, and a methodical program of training experiences. Part of that program, at least in this book, is the establishment of a manageable range of fundamental procedures and a set of simple and sensible habits. Most of the major pitfalls in brewing can be avoided by adopting proven techniques and by methodically recording details of the process and its results indelibly. Good, natural brewing starts with high standards of quality and freshness of ingredients, along with persistently close attention to temperature, specific gravity, and sanitation. To a large extent, the metabolic pathways of your yeasts will take care of themselves in the presence of the right materials and under the right environmental conditions. This approachyeast husbandryrequires that you routinely make measurements, be observant and understanding about the biology of yeasts, and do a few calculations, but it will start you in the direction of becoming a competent and predictably excellent brewer.

Gaining experience beyond the elementary skill required to make decent beer, and learning to craft excellent, original beers is an important transition toward better brewing, and you can get there quickly. A better understanding of yeast and grain biology is the sort of knowledge that is necessary to accomplish this. Still, do not let intermediate brewing be a daunting prospect. It has been said that we learn about 5% of what we are told, 10% of what we read, and about half of what we experience. If those results are additive, it might follow that active engagement in hands-on activities guided by a good instructional book might impart about 60% of the desired knowledge, which is certainly better than trial-and-error learning. There will be mistakes, and they should be avoided but mistakes can help you learn fast. Producing an unpalatable batch of beer invariably leads to a careful re-examination of the methods used and some motivation to improve. The sight and possibly the cost of five gallons or more of spoiled beer going down the drain is a potent inducer of fastidiousness. Can there be a stronger incentive for upgrading ones talents than a complete catastrophe of this sort?

Next page