IN COMPETITION, you can run with the big dogs, and learn from them. This is world champ Dave Sevigny, with his trademark Glock.

Every bit of information that may be picked up on the range will prove useful in war. True, it will not always nor often be possible to assume the exact, orthodox positions used in competitions and there is the matter of adjusting oneself mentally and physically to the stress and strain of battle but, just the same, all those fundamental principles will have an important, even if sub-conscious influence, tending to increase the riflemans effectiveness.

From Herbert W. McBrides introduction to his classic book, A Rifleman Went to War

Earlier in this book, we saw that one thing Wyatt Earp, Charlie Askins, and Jim Cirillo had in common was that they competed in the pistol matches of their time. All seemed to feel that this experience stood them well when they had to compete against men who were pointing their guns at them instead of at the same bank of targets as they were.

Early in my career I had the good fortune to know and be mentored by Lt. Frank McGee, the legendary NYPD firearms trainer. Frank was the one who turned the departments firearms training unit into the Firearms and Tactics Unit (FTU). He incorporated practical shooting stances instead of target shooting into the marksmanship side of it. He was the first on NYPD to use role-play training. He emphasized such tactical elements as the use of cover, arraying automobiles, mailboxes, and telephone poles on the ranges of the training facility at Rodmans Neck in the Bronx to get the cops accustomed to putting something between them and the incoming fire that at least some of them would inevitably face.

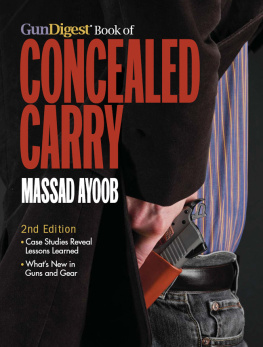

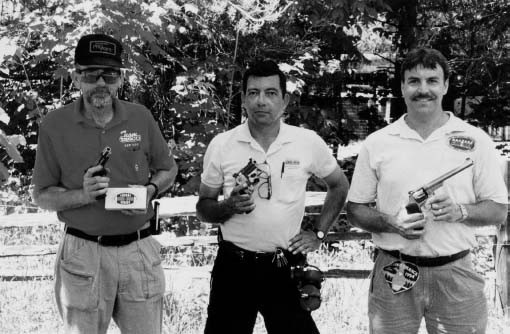

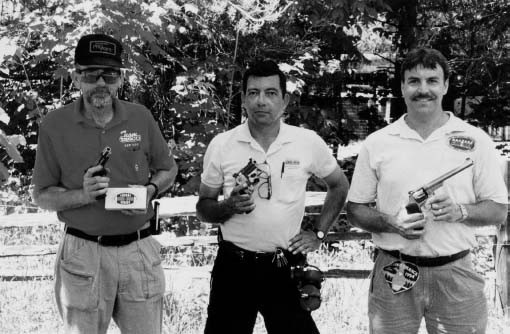

TOP THREE SHOOTERS in Master Stock division at Second Chance national shoot, early 1990s. From left: 1st place Ken Tapp, with Springfield Armory .45 auto; 2nd place Mas Ayoob, with four-inch S&W 625 .45 ACP tuned by Al Greco; 3rd place Mike Shovel, with 8 3/8-inch Model 25, also tuned by Greco. All shot for Team CorBon and used +P .45 ACP ammo.

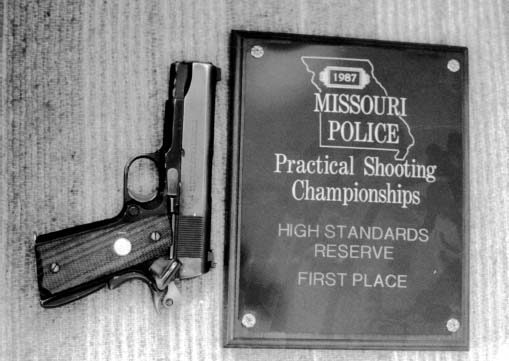

COMPETING WITH THE GUN you actually carry is the most relevant competition as component of training experience. This one is a Colt Lightweight Commander .45, tuned for duty by Bill Laughridge at Cylinder & Slide.

Franks unit was responsible for gathering the information for SOP-9. Inaugurated circa 1970, Standard Operating Procedure Number Nine was an in-depth debriefing of every MOS (Member Of the Service) involved in any sort of discharge of a weapon outside the training ranges. The debriefing included such questions as, Did you use your sights? Did you fire double action or single if you used a revolver? What was your shooting position at each point in the fight? Did you hold the gun with one hand or two? The responses would be correlated with facts learned from the investigation, such as how many shots were fired vis--vis how many hits, at what distance, and similar things.

It occurred to members of the Firearms and Tactics Unit that it would be useful to cross-reference the hit percentage in actual gunfights of each member of the department, with what that members score was in regular qualification at the main NYPD range at Rodmans Neck and the satellite indoor ranges around the city. Quite apart from the obvious benevolent interest in officer safety if the more highly skilled shooters were more likely to survive, the city might budget more money to train more officers to that skill level the FTU also stood to benefit from a positive correlation. If their training in marksmanship skill was saving more lives, they would get much positive reinforcement.

Alas, Lt. McGee told me, there was no correlation to be found. Not the expected positive correlation of high scores equaling high field performance, but no negative correlation either that might have indicated good shooting skills were somehow deleterious to survival-oriented performance. With this in mind, the FTU simply redoubled its emphasis on tactics and mindset, which unquestionably did improve gunfight outcomes and save officers lives.

In the years since, other instructors around the country came to the same conclusion. However, while never officially studied by a police department to my knowledge, there is another comparison that results in a different conclusion. Those who shoot in competition seem to have a remarkably high hit potential and survival ratio in actual gunfights.

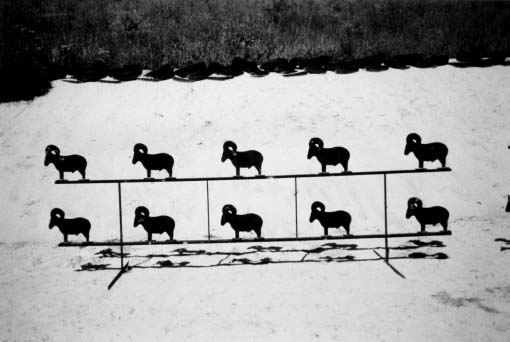

AT 100 METERS, these half-size steel ram silhouettes in NRA Hunter Pistol are challenging targets for a combat handgun, and great confidence builders for the practitioner.

ONE-HANDED SHOOTING at seven yards is part of some police combat matches, and a valuable survival skill.

Historical Precedent

This seems to have been pointed out by soldiers before it was pointed out by cops. In his book A Rifleman Went to War, H. W. McBride wrote extensively of his experiences in the trenches and on the battlefields of WWI. He had been a competitive rifle shooter before signing up so he could fight in The Great War. Once on the battlefield he killed soldier after enemy soldier, one bullet at a time, with the unerring marksmanship he had learned on competitive rifle ranges in North America.

After WWII, Lt. Col. John George wrote Shots Fired In Anger, subtitled A Riflemans View of the War in the Pacific, 1942-1945. He had begun his adulthood as a skilled competitive rifle shooter. He felt that skill would serve him well in the jungles of the Pacific Theater. It did. His outstanding book shows multiple cases where he used essentially the same techniques, and the same coolness under stress, in combat that he used on shooting ranges. The result was a very significant number of enemy deadand an American fighting man who returned home both victorious and unscathed after extensive mortal combat.

Fast forward to the Vietnam conflict. The most famous rifleman to emerge from it was Carlos Hathcock, memorialized in the biography Marine Sniper by Charles Henderson. Hathcock was credited with 93 confirmed kills of enemy personnel, some at extraordinary distances and under extraordinary circumstances. Perhaps the most storied was the incident in which he faced another master sniper. The man was aiming at him as Hathcock put a bullet through the enemys telescopic sight from front to back, into his eye, and thence into his brain, killing him barely in time to save his own life.

Hathcock had been a member of the U.S. Marine Corps rifle team, the crme de la crme of American military marksmanship, and had won the Wimbledon Cup, which is essentially the United States Championship of long range shooting with high powered rifles, before ever seeing an enemy combatant in his gunsights. It is apparent that the 93 confirmed kills were merely the tip of the iceberg, due to the strict reporting requirements of the USMC Scout Snipers, and that his actual body count was well into three digits. It is clear that the coolness, the focus, and the mastery of his weapon under pressure that he learned on the rifle ranges of Quantico and Camp Perry translated extremely well to the jungles and rice paddies of Southeast Asia.