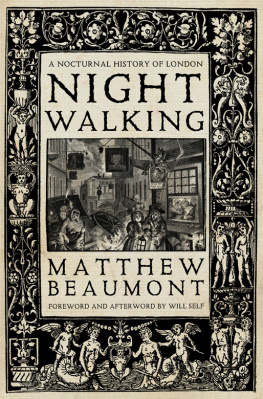

p. 1: From London Night by John Morrison and Harold Burkedin, 1934

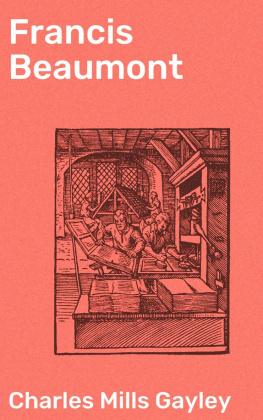

p. 73: A Most Wicked Work of a Wretched Witch, printed by Richard Burt,

c. 1592 (woodcut), English School (sixteenth century) /

Lambeth Palace Library, London, UK / Bridgeman Images

p. 109: Times of the Day: Night, from The Works of William Hogarth,

1833 (litho), William Hogarth (16971764) / Private Collection /

Ken Welsh / Bridgeman Images

p. 261: Colinets Fond Desire to Know Strange Lands, illustration from

Dr Thortons The Pastorals of Virgil (woodcut), William Blake (17571827) /

Southampton City Art Gallery, Hampshire, UK / Bridgeman Images

T he Leverhulme Trust funded the research on which this book is based and, first and foremost, Id like to thank this institution for its generosity in awarding me a Research Fellowship in 201213. At a time when scholarly activity is more and more instrumentalized, more and more closely monitored, the Leverhulme Trust is exemplary for the freedom and independence it affords the academics whose scholarship it sponsors. I owe a deep debt of gratitude to those who supported my application: Rachel Bowlby, Terry Eagleton, Kate Flint, Colin Jones and Jo McDonagh.

My thanks go to the following for making reading suggestions, inviting me to present my ideas in the form of papers and lectures, or, more generally, providing me with encouragement and support in this project: Tariq Ali, Rosemary Ashton, Jo Barratt, Tim Beasley-Murray, Amelia Beaumont, Joanna Beaumont, Michael Beaumont, Sebastian Budgen, Ardis Butterfield, Stephen Cadywold, Ben Campkin, Warren Carter, Gregory Claeys, Holly Clayson, Oskar Cox Jensen, Greg Dart, Paul Davis, Joseph Drury, Ger Duijzings, Geoff Dyer, Gavin Everall, Mark Ford, Anita Garfoot, Helen Hackett, Andrew Hemingway, Clive Holtham, Philip Horne, Ludo Hunter-Tilney, Colin Jones, Natalie Jones, Tom Keymer, Roland-Franois Lack, Eric Langley, Andy Leask, Rob Maslen, Jo McDonagh, China Miville, John Mullan, Andrew Murray, Lynda Nead, Katherine Osborne, Francesca Panetta, William Raban, Neil Rennie, Jo Robinson, Will Self, Jane Shallice, Natasha Shallice, Bill Sharpe, Alison Shell, Nick Shepley, Nick Shrimpton, Chris Stamatakis, Gabriel Stebbing, Hugh Stevens, Matthew Sweet, Jeremy Tambling, John Timberlake, Sara Thornton, Susan Watkins, Abigail Williams and Henry Woudhuysen. Those friends, colleagues and acquaintances who made reading recommendations relating to nightwalking in the later nineteenth or twentieth centuries will, Im afraid, have to be thanked in the sequel to this book.

For reading chapters in draft form and offering perceptive and constructive criticism, I am especially grateful to Michael Beaumont, Greg Dart, Paul Davis, Helen Hackett, Ludo Hunter-Tilney, Jo McDonagh, Nick Papadimitriou and Chris Stamatakis. Above all, I am grateful to Will Self, who read the entire book in draft form and whose support throughout its composition has been of incalculable importance to me.

Tom Penn commissioned this book, though he has since moved to Penguin, and Id like to record my heartfelt gratitude to him. Leo Hollis inherited the project, but his commitment to it has been unstinting and in his reading of the manuscript he has been as encouraging as he has been penetrating I could not have hoped for a better editor. My sincere thanks, too, to Mark Martin, in Versos New York offices, for overseeing the books production so efficiently; and to Charles Peyton for his judicious copyediting.

Finally, for accompanying me on nightwalks in London and its fringes on various occasions over the last couple of years, I owe special thanks to Ludo Hunter-Tilney, Nick Papadimitriou, Will Self and David Young. These walks, and the meandering conversations that accompanied them, have influenced this book in ways that, though perhaps not immediately apparent, have nonetheless been of crucial importance. This page too, as the poet Octavio Paz wrote in his Nocturno de San Ildefonso, is a ramble through the night.

The book is dedicated, with all my love, and in admiration, to my sons Jordan and Aleem Beaumont.

I n the Oxen of the Sun episode of Ulysses, having encountered each other en passant earlier in the day, the novels two protagonists are finally thrown together. Seated with a bunch of rowdy medical students and their assorted hangers-on in the hall of Dublins Holles Street maternity hospital, Leopold Blooms paternal feelings are aroused by the spectacle of Stephen Dedalus who, while surpassing eloquent, is nonetheless sinking deep into his cups. As Mrs Purefoy struggles through the endgame of her three-day labour in the ward above, so the novels narrative struggles through chronologically successive English prose styles, from alliterative Anglo-Saxon to the rambunctious discursiveness of Dickens. The familiar analysis of these parodies is that they are a conflation of ontogeny and phylogeny: just as the Purefoy babys gestation is assumed (by Joyce, in line with the scientific thinking of the day) to have recapitulated the stages of human evolution. So the text itself undergoes mutagenesis: its physiology and morphology altering to adapt to changed environments.

But if Mrs Purefoy gives birth to an infant, what precisely is it that the contractions and dilations of Joyces prose give birth to? In part, it is to an actualization of the paternal feeling that Bloom has towards Stephen. But this sentiment finds its fuller expression in what they do together, which is to walk specifically, to nightwalk. First, seriatim, they proceed to Mrs Bella Cohens brothel at 82 Lower Tyrone Street; then, entwined, they progress to the cabmans shelter by Butt Bridge; finally, in concert, they head to Blooms house at 7 Eccles Street.

Here, Bloom, after a long and eventful day, is able to think himself and then actually be at home; but for Stephen the situation is more problematic. The complacently cuckolded Bloom has absented himself from Eccles Street so his wife may keep an assignation. He is also, as a canvasser of newspaper advertisements, a peripatetic worker; moreover he partakes in virtue of his ancestry of the Wandering Jews mythos, just as his diurnal divagations resonate with the decade the Homeric Odysseus took to return home to Ithaca after the Trojan War.