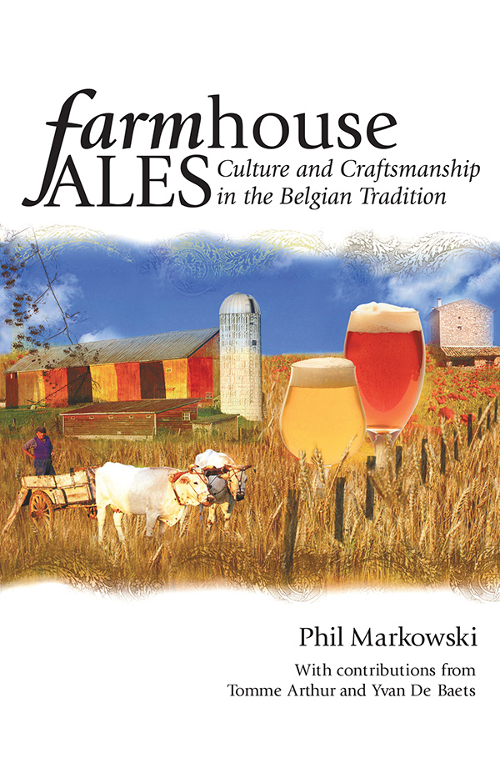

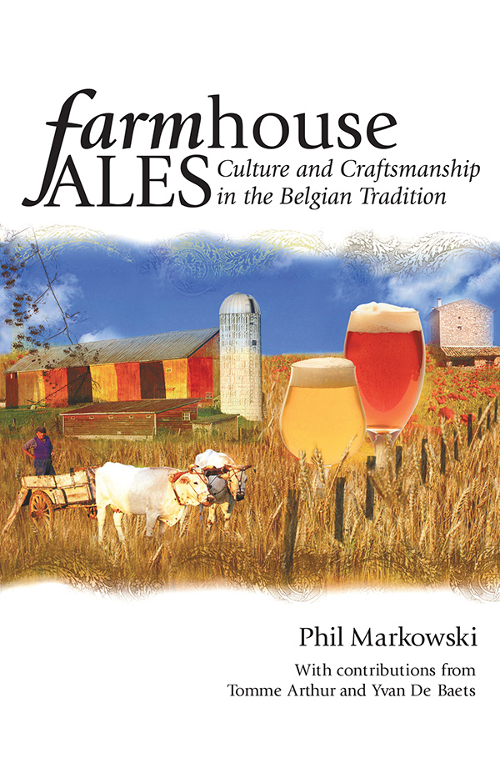

Farm house ALES

Culture and Craftsmanship in the Belgian Tradition

Phil Markowski

With contributions from

Tomme Arthur and Yvan De Baets

Brewers Publications

A division of the Brewers Association

PO Box 1679, Boulder, CO 80306-1679

BrewersAssociation.org

2004 by Phil Markowski

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission of the publisher. Neither the author, editor nor the publisher assume any responsibility for the use or misuse of information contained in this book.

ISBN: 0-937381-84-5

E-ISBN: 978-0-9840756-7-6

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Markowski, Phil.

Farmhouse ales : culture and craftsmanship in the Belgian tradition / Phil Markowski ; with contributions from Tomme Arthur and Yvan De Baets.

p. cm.

Includes .

ISBN 0-937381-84-5

1. Ale--Flanders--History. I. Title.

TP578.M34 2004

641.23094931--dc22

2004023123

Publishing Editor: Ray Daniels

Technical Editor: Randy Mosher

Copy Editor: Jill Redding

Index: Daria Labinsky

Cover Design: Julie Korowotny

Cover Illustration: Naomi Shea

Photos: Scott Morrison, Dan Shelton and Matt Stinchfield

Table of Contents

T he list of people to thank is a long one. At the top is my wife, Maryann, for her patience and supportbefore, during, and after this project. More of the same goes to the Sullivan brothers, owners of the Southampton Publick House, who allow me the freedom to endlessly experiment in a commercial brewery. Thanks go to Yvan De Baets, a native Belgian whose passion for his countrys brewing tradition is equaled only by his willingness to share and exchange information. To Daniel Shelton, for all his help and for importing the best of these artisanal ales into the United States. To Randy Mosher, for lending more than a helping hand. To my translators, B. R. Royla and Yvan De Baets, and to the Belgian and French brewers who were willing to share information, enthusiasm, and insight into their methods and techniques.

With regard to visual content, this book would not be the same without significant contributions from several people. I would like to thank Scott The Dude Morrison for his photos as well as his enthusiasm and superior navigational skills. A substantial collection of photos were contributed by Dan Shelton and Matt Stinchfield to enhance nearly every section of this text. Finally, we have many, many labels of Belgian beers, many of which came from the collection of Jos Detournay and Stef Caenepeel. Many thanks to them for sharing their treasured collection.

To Patricia Ann Sullivan, loving mother and avid reader. She would have gotten a kick out of knowing that her son went on to become a brewer, and a bigger kick to know he wrote a book on the subject. To my father, Sylvester A. Markowski, who, among the many things he gave me, let me have my first sip of beer at age 5. I didnt like it at the time, but look where it took me.

I learned at an early age that beer and hard labor go together.

Growing up in the coastal city of San Diego, I never lived on a farm. Still I learned early about labor as my father put me to work in his print shop as soon as I could push a broom. But no matter how tedious, such exertions paled in comparison to the inevitable demands of yard work.

On weekends, we Arthur children were bound into suburban slavery on our corner lot with large front and back yards. The house had previously been owned by a gardener and was landscaped in every conceivable way. While I endured many days of backbreaking labor, my earliest memories of toil had me chasing around an old-school, rear-discharge lawnmower.

Through the years of blood, sweat, and tears in that yard, I remember three constants: a lawn mower that rarely ran well, the sweet smell of freshly mown grass, and a swig of my dads lager at the end of the day. Even now, my mouth waters at the thought of each sip stolen from his cold, crisp beer. Even then, those tiny bubbles offered momentary emancipation from that most American of labors: the drudgery of the suburban lawn.

Of course I have never worked as a saisonnier in the fields of Wallonia where backbreaking labor was the norm. I reckon I wouldnt have fared all that well. Like most modern kids, most of my days were filled with a different sort of labor. Adults call it schoolwork.

Despite extensive studies, American high schoolers rarely consider the history of Belgium. Although I scored well in geography class, I cant recall being asked to point out Wallonia on a map. Our books and teachers enlightened us only slightly about the World Wars and the role the Belgian people played. Instead of European geography, I learned important things like the capital of South Dakota and the most likely places to mine for coal.

Now, as a brewer with a keen interest in Belgian beers, I am more aware of the countrys beer producing regions. I can even find Wallonia on a map. More importantly, I can tell you about the beers made there, even though they are only a minor component of the local economy.

As a brewer, my geographic boundaries broaden with each new beer I sip. Over the last five years, I have been road tripping through Wallonia and northern France one bottle at a time. The rustic producers in this region have become some of my favorite beers including the peppery saisons of Brasserie Dupont and the seasonal anomalies of Brasserie Fantome. I also have grown to love the musty cellar qualities of bires de garde. Of the beers that I regularly consume, I find these to be rewardingly flavorful while at the same time refreshingly straightforward.

I believe these styles to be among the most versatile of beers, offering a wide range of flavors from one producer to the next. They make deft companions for fish and salads but can also be cellared for many months, held back until they develop their delightful yet understated complexities.

Much has been written about these beers of late and brewers everywhere seek to recreate and explore both traditional and modern farmhouse brews. Students of this realm understand them as the beers of an agrarian society. As such, their character has been shaped less by the fickleness of consumer tastes and more by farm operations and the need to nourish a staff of laborers. Because these beers belong to a family of products with, in my opinion, no stylistic absolutes, few sources of authoritative information can be found. This fact hampers both our understanding of these beers and our ability to research them effectively.

This problem faced Phil Markowski head-on when he tackled this project. As brewers, we conduct research on beers and this can be an arduous and difficult task with each frothy pint rearing its head. I know from conversations with Phil just how complicated undertaking a book like this can be. I applaud his fastidious determination and resolve to add to the brewing canon. A resource like this comes along when information is scarce and an author is inspired to put forth effort and a commitment to due diligence.

Yvan De Baets makes a worthy addition to the text, extending our view of the style. Through his perspective, we can reconsider the saison we know and love today with the saison of a more rustic time. We may also be persuaded that these beers share primitive roots with the likes of lambic and Berliner Weisse through their microbial predispositions. I love the thought-provoking nature of this chapter and the historical tapestry it provides for the foundations of modern farmhouse brewing.

Next page