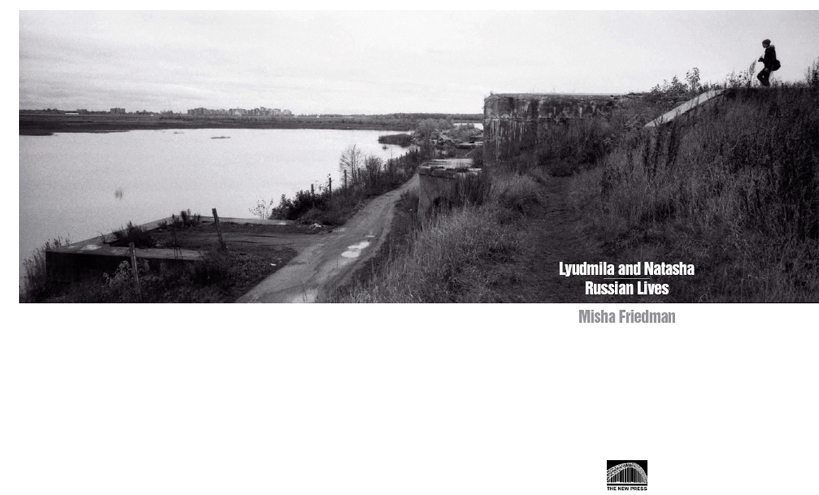

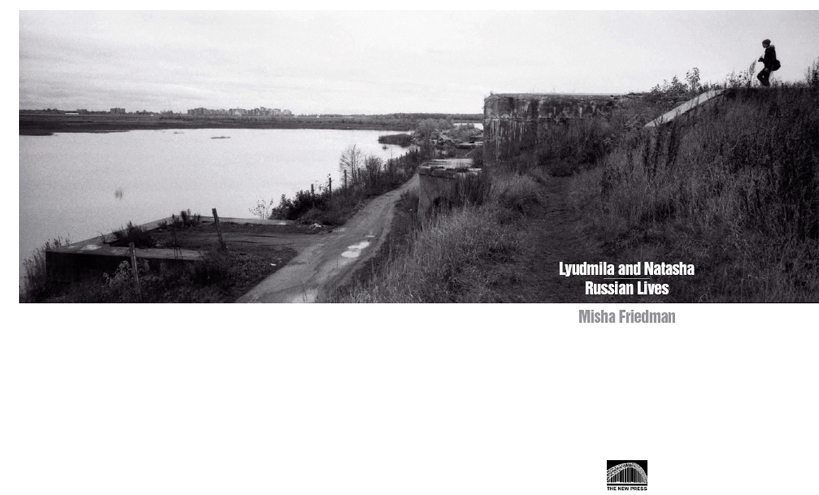

Lyudmila and Natasha

2014 by Misha Friedman

Preface 2014 by Jon Stryker

Introduction 2014 by Jeff Sharlet

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, in any form, without written permission from the publisher.

Requests for permission to reproduce selections from this book should be mailed to:

Permissions Department, The New Press, 120 Wall Street, 31st floor, New York, NY 10005.

Published in the United States by The New Press, New York, 2014

Distributed by Perseus Distribution

ISBN 978-1-62097-054-6 (e-book)

CIP data available

The New Press publishes books that promote and enrich public discussion and understanding of the issues vital to our democracy and to a more equitable world. These books are made possible by the enthusiasm of our readers; the support of a committed group of donors, large and small; the collaboration of our many partners in the independent media and the not-for-profit sector; booksellers, who often hand-sell New Press books; librarians; and above all by our authors.

www.thenewpress.com

Book design and composition 2014 by Emerson, Wajdowicz Studios (EWS)

This book was set in Helvetica Inserat, Helvetica Neue, Franklin Gothic, News Gothic and Roman Cyrillic Std.

Printed in the United States of America

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Contents

By Jon Stryker

The photographs in this book and future books anticipated in this series are part of a larger collective body of commissioned work by some of the worlds most gifted contemporary photojournalists. The project was born out of conversations that I had with Jurek Wajdowicz. He is an accomplished art photographer and frequent collaborator of mine, and I am a lover of and collector of photography. I owe a great debt to Jurek and his design partner, Lisa LaRochelle, in bringing this book series to life.

Both Jurek and I have been extremely active in social justice causesI as an activist and philanthropist and he as a creative collaborator with some of the household names in social change. Together we set out with an ambitious goal to explore and illuminate the most intimate and personal dimensions of self, still too often treated as taboo: gender identity and expression and sexual orientation. These books will reveal the amazing multiplicity in these core aspects of our being, played out against a vast array of distinct and varied cultures and customs from around the world.

Photography is a powerful medium for communication that can transform our understanding and awareness of the world we live in. We believe the photographs in this series will forever alter our perceptions of the arbitrary boundaries that we draw between others and ourselves and, at the same time, delight us with the broad spectrum of possibility for how we live our lives and love one another.

We are honored to have Misha Friedman as a collaborator in Lyudmila and Natasha. He, and the other photographers among our partners are more than craftsmen; they are communicators, translators, and facilitators of the kind of exchange that we hope will eventually allow all the worlds peoples to live in greater harmony.

By Jeff Sharlet

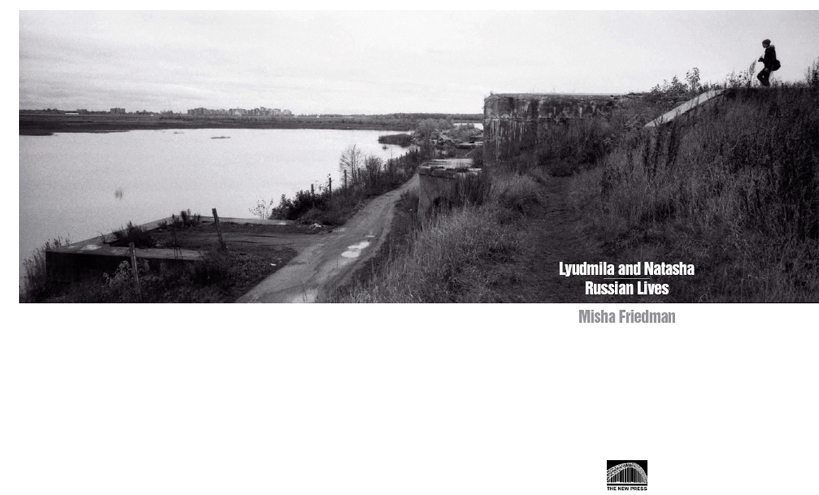

Here is a book about a couple, Lyudmila and Natasha, who appear in these photographs to be in love with one another, and who say they are in love, and who struggle. Because thats what we do when were in love. We struggle to hold onto one another, to ourselves, to a moment that is always leaving. Its like trying to hold on to a river, as if Lyudmila and Natasha have attempted to wrap their arms around the Neva with which this hard, beautiful, struggling book begins. Hold on to a river? Impossible. It cant be done. And yet we try, we try. This is our struggle as people in love, or people who remember love, or people waiting for loves return; that is why we recognize ourselves in Lyudmila and Natasha, two ordinary women in love, remembering love, waiting for each others return.

See Lyudmila and Natasha on the cover, chin to nose like yin and yang, lips between seeking connection. Contact, a kiss, completion. But its never so simple. opens with individual portraits, Lyudmila and Natasha each alone, separated from one another, broken up. Each speaks to Misha Friedman, to the camera, and through the camera to one another: I would like to be with Natasha, says Lyudmila, in soft light and gentle shadow. With my love. Natashasun drawing a sharper line across her eyesI dont have superhuman powers to fall in love just because I want to.

But she does. Thats the spoiler. This is a love story, after all. Common as water, as hard to grasp as a river. That Misha Friedman comes so close is his great achievement, his gift to us. Friedman has become like one of Wim Wenderss angels in Wings of Desire, a recording angel, an angel with a notebook and a camera, documenting the ordinary and by doing so revealing it as extraordinary. There are no iconic images here, no V-J Day in Times Square kiss, no Doisneaus Le baiser de lhtel de ville. Instead of the grand gesture, we have the real embrace. Consider Natasha through Lyudmilas eyes as they make love (), Natasha stunned and yet searching, seeing Lyudmila so fully that we see her, too. We are looking over Lyudmilas shoulder and yet seeing with Natashas eyes. Fleeting yet intimate, like water rushing around us.

These are the moments I prize most in Lyudmila and Natasha, but theyre not why Ive been asked to write an introduction. My connectionbeyond the human one anyone with eyes and heart can share with images as grainily specific and universal as theseis with the setting for Lyudmilas and Natashas love and struggle, Saint Petersburg: in particular, Russia more widely. Its not my settingI am neither a Russian nor a Russophile; I admire Saint Petersburg, but I cannot name the streets in these pictures. I am no expert. All I know is Article 6.21, signed into Russian law by President Vladimir Putin on June 30, 2013, after a vote in the Duma of 4360.

The language of the law is dull and deliberately vague, designed to deter close reading. So let us struggle with it:

Propaganda of nontraditional sexual relations among minors, manifested in the distribution of information aimed at forming nontraditional sexual orientations; the attraction of nontraditional sexual relations; distorted conceptions of the social equality of traditional and nontraditional sexual relations among minors; or imposing information on nontraditional sexual relations that evoke interest in these kinds of relationsif these actions are not punishable under criminal lawwill be subject to administrative fines.

Its almost genius in its perversion. Consider, especially, the third clause, outlawing distorted conceptions of the social equality of traditional and nontraditional sexual relations. What does it mean? Only this: in Russia, now it is a crime for Lyudmila and Natasha to assert that their love matters as much as that of a man and a woman. It is a crime to assert that they could ever even love each other as much as a man and a woman. If Lyudmila tells her two sons that she loves Natasha just as much as their father loves their stepmother, she is breaking the law. She might be forbidden from seeing her children.

Article 6.21 does not forbid sexual relations. It is not a revival of the Soviet-era Article 121, which punished sex between men with prison terms as long as five years. (Only menlesbians and other queer relations were, apparently, beyond the throttling grip of Stalins imagination.) Article 6.21 is subtler than that. Its more like a resurrection of the Soviet-era Article 70, which simplysimply!banned anti-Soviet agitation and propaganda. What constitutes propaganda? The police will inform you after your arrest. Or they may not. Best not to say anything at all. So, were it not for the fact that until just a few years ago LGBT rights in Russia were steadily advancingwere it not for the fact that a proposal similar to Article 6.21 was laughed out of the Duma as hopelessly provincial without a vote as recently as 2006were it not for these facts we might say Article 6.21 provides a kind of progress. Its not as all-encompassing as Article 70. Article 6.21 provides focus. Its concerned with merely one or two aspects of life: love and sex, sex and love, and, for good measure, anything to do with children, because we must protect the children. From what?

Next page