Philippa Carr

Lament for a Lost Lover

Strolling Players at Congrve

ALTHOUGH I DID NOT REALIZE IT AT the time, the day Harriet Main came into our household was one of the most significant of my life. That Harriet was a woman to be reckoned with, that she had an outstanding and very forceful personality, was obvious from the first, and that she should take on the post of governessthough brieflywas altogether incongruous, for governesses are usually subdued in manner, eager to please and so much aware of the precarious nature of their employment that they suffer acute apprehension, which they cannot help betraying to those who are in a position to take advantage of it.

Of course the times were extraordinary and since the Great Rebellion had brought about such change in England, everything, as people about us constantly said, was topsy-turvy. Here we were, exiles from our native land, living on the hospitality of any foreign friends who would help us; and although it was a comfort to remember that the King of England shared our exile, that did not help us materially.

Being seventeen in this year 1658 and having fled with my parents when I was ten years old, I should be accustomed to the life by this timeand I suppose I was; but vivid memories lingered with me and I liked to talk to my brothers and sister of the old days, which made me appear wise and knowledgeable in their eyes.

There was so much talk of that past and so much speculation as to when it would return that it was constantly in our minds, and as no one ever expressed a doubt that it would, even the little ones were ready to hear the same stories of past splendours in the Old Country over and over again, for in recording them one was not only talking of the past but of the future.

Bersaba Tolworthy, my mother, was a woman of strong character. She was in her late thirties but looked like a much younger woman. She was not exactly beautiful but she had a vitality which attracted people. My father adored her. She represented something to him and so did I, for of all the children I was his favourite.

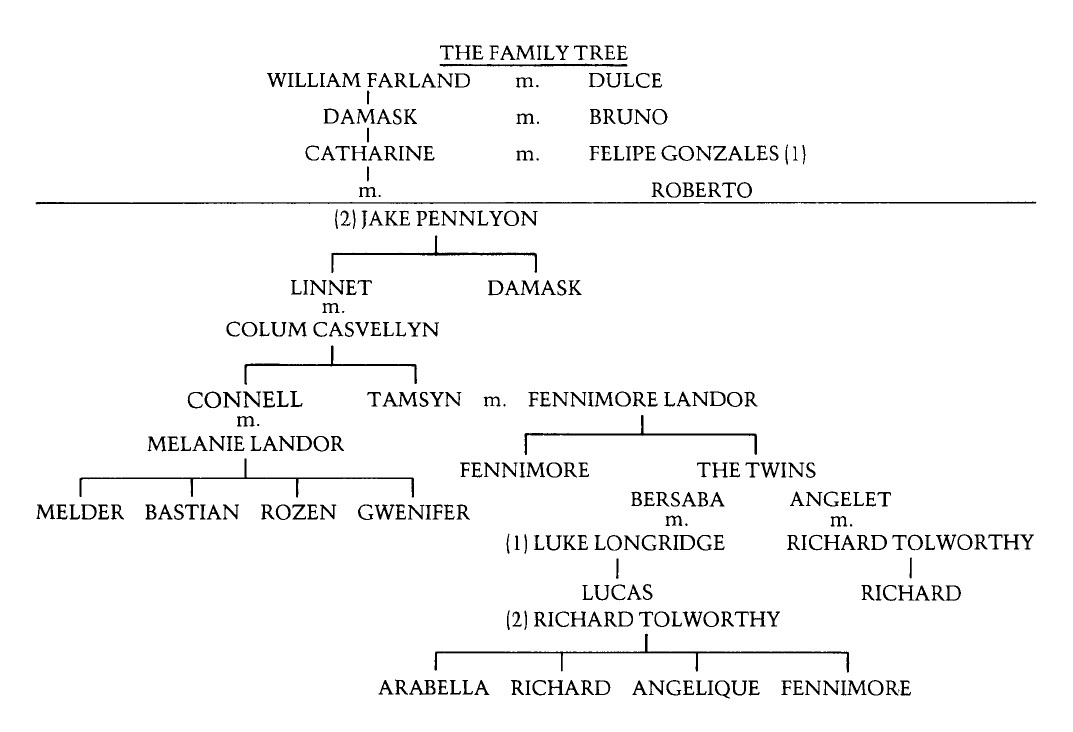

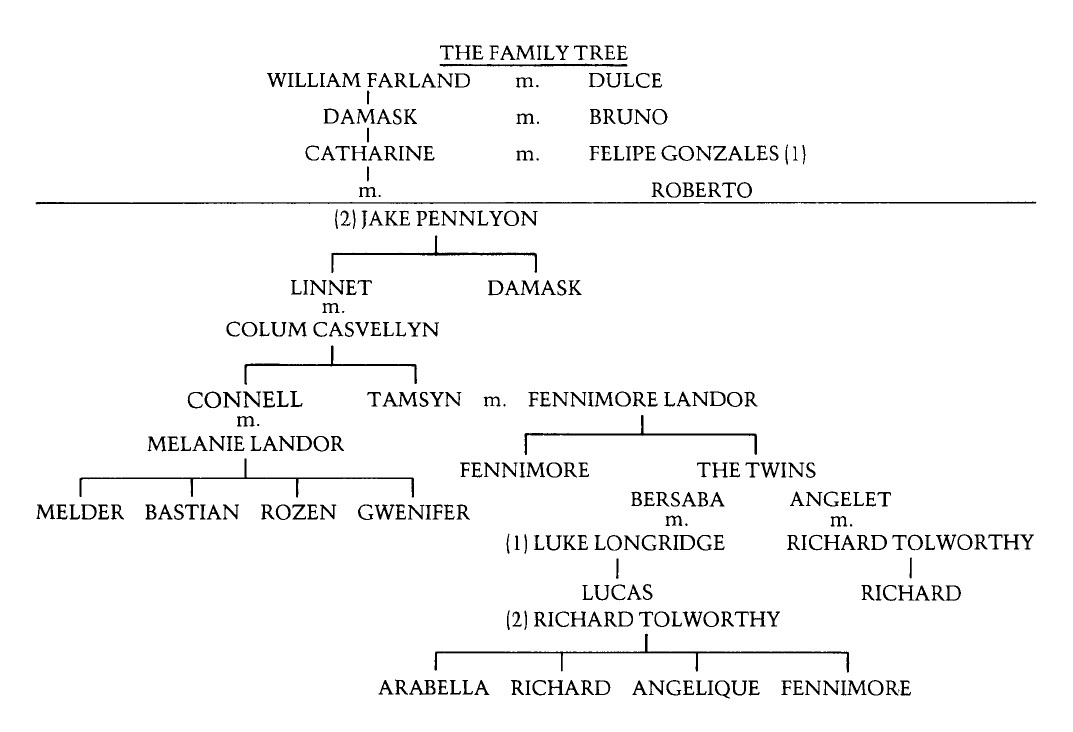

My mother kept a journal. She told me that her mother, whom I remembered, for we had stayed with her in Cornwall before we fled from England, had presented her and her sister Angelet with journals on their seventeenth birthdays and told them that it was a tradition in the family that the women should keep account of what happened to them and that these were preserved together in a locked box. She hoped I would carry on the custom, and the idea appealed to me. Particularly as there were journals going right back to my great-great-great-grandmother Damask Farland who had lived at the time of Henry VIII.

These journals cover not only the lives of your ancestors but tell you something about the events which were of importance to our country, said my mother. They will make you understand why your ancestors acted in the way they did.

Because there was something rather odd about my birth and she thought I should understand the position better if I knew exactly how it happened, she gave me her journals to read when I was sixteen.

She said: You are like me, Arabella. You have grown up quickly. You know that you have not the same father as Lucas, but share him with the little ones. That could be puzzling and I would not have you think that you did not belong to your father. Read the journals and you will understand how it came about.

So I read of my maternal ancestors, of gentle Dulce, Linnet and Tamsyn, of wild Catharine and my mother Bersaba, and as I progressed I realized why my mother had given me these diaries. It was because she thought there was something of Catharine and herself in me. Had I been like the others and her own sister, my Aunt Angelet who was now dead and whose life was so entwined with that of my mother, she might have hesitated.

So I learned of the stormy love of my mother and father, which they secretly consummated while he was married to Angelet, and of how because I was about to be born, my mother had married Luke Longridge and from that marriage came my half brother, Lucas, who was less than two years my junior. Luke Longridge had been killed at Marston Moor, and Angelet had died when her baby was born, but it was years after when my father and mother found each other. By that time the Royalist cause for which my soldier father had been fighting was lost, Charles I beheaded and Charles II had made a desperate and unsuccessful attempt to gain the throne. He had escaped from England, and my father and mother with Lucas and me joined the exiles in France.

Since then they had had three children, Richard named after my father, so always called Dick to distinguish them; Angelique, named with my mothers twin sister in mind although she had been Angelet, and FennFennimoreafter my mothers father and brother.

That was our family living the strange lives of exiles in a strange land, every day waiting to hear from England that the people were tired of Puritan rule and wanted the King back; when he went, we as staunch Royalists would go with him.

My mother used to say: A plague on these wars. I could be for the side which would let the other live in peace. I knew from her diary that she had been married to a Roundhead as well as a Cavalier, and that Lucas must remind her sometimes of his father. But the love of her life was my fatherand she was hisand I knew she would be on his side whichever that was. When they were together in our companyand that was not often, for he was a great general and must follow the King to be ready if ever it was decided to make a bid for the thronetheir feeling for each other was obvious.

I said to Lucas: When I marry I want my husband to be like our father is with our mother.

Lucas did not answer. He did not know that we had not the same father. He couldnt remember his own, and he was called Lucas Tolworthy, though he had been born Longridge as I suppose I had. He hated the thought of my marrying, and when he was a little boy he used to say he was going to marry me. I had bullied him, for I was of a dominating nature. Lucas used to say that the little ones were more afraid of me than of our parents.

I liked everything to be orderly and that meant done the way I wanted it, and because we were left a good deal alonefor when my father went away my mother accompanied him whenever possibleit did mean that I fancied myself as the head of the family. Being the eldest I slipped naturally into the role, for although I was less than two years older than Lucas, there was a big gap between Lucas and me and the little ones.

I could remember so well the time when we had left for France and before it too, for I was after all ten years old. I have vague pictures of Far Flamstead and the terror I sensed in the house when we were waiting for the soldiers to come. I can remember hiding from them and catching the fear of the grown-ups, which I only half believed was real; then I remember a new baby and my Aunt Angelet going to Heaven (as I was told) and how we went traveling interminably it seemed to Trystan Priory, which is clear in my memory even though it was seven years since I left it. My cozy grandmother, my kindly grandfather, my Uncle Fenn it is there forever in my memory. I can remember second cousin Bastian riding over from Castle Paling and always trying to be alone with my mother. Then suddenly it all changed. My father came. I had never seen him before. He was tall and grand and could have been frightening, but he did not frighten me. My mother has said: When youre frightened just stand and look right in the face of what frightens you and you will very likely find there is nothing to fear after all.