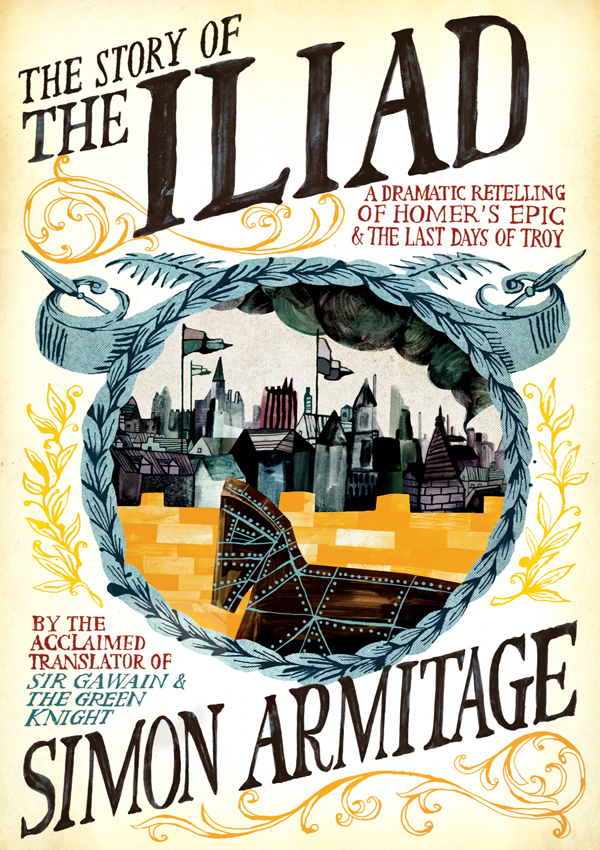

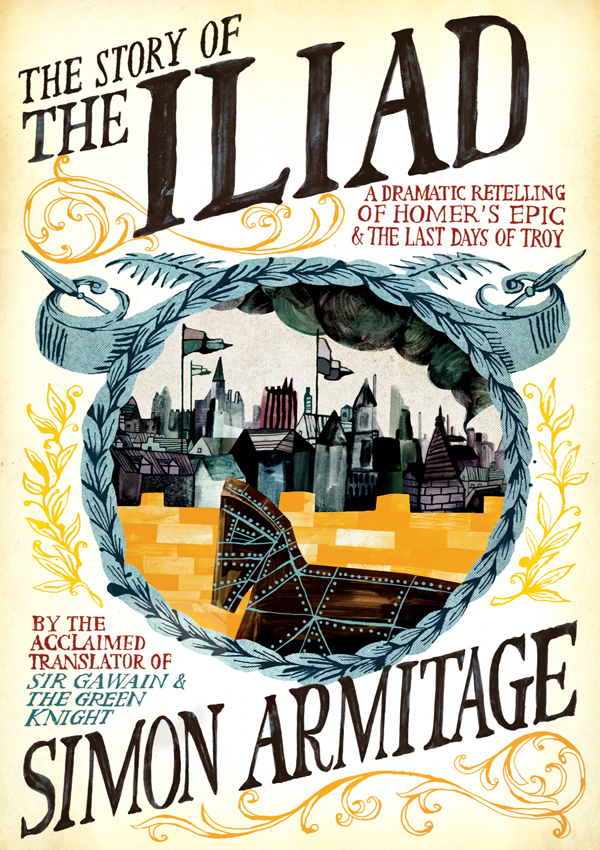

by the same author poetry ZOOM! XANADU KID BOOK OF MATCHES THE DEAD SEA POEMS CLOUDCUCKOOLAND KILLING TIME SELECTED POEMS TRAVELLING SONGS THE UNIVERSAL HOME DOCTOR TYRANNOSAURUS REX VERSUS THE CORDUROY KID SEEING STARS SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT THE DEATH OF KING ARTHUR drama MISTER HERACLES (after Euripides) JERUSALEM HOMERS ODYSSEY prose ALL POINTS NORTH LITTLE GREEN MAN MOON COUNTRY (with Glyn Maxwell) THE WHITE STUFF GIG WALKING HOME The Story of the Iliad A Dramatic Retelling of Homers Epic and the Last Days of Troy SIMON ARMITAGE

by the same author poetry ZOOM! XANADU KID BOOK OF MATCHES THE DEAD SEA POEMS CLOUDCUCKOOLAND KILLING TIME SELECTED POEMS TRAVELLING SONGS THE UNIVERSAL HOME DOCTOR TYRANNOSAURUS REX VERSUS THE CORDUROY KID SEEING STARS SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT THE DEATH OF KING ARTHUR drama MISTER HERACLES (after Euripides) JERUSALEM HOMERS ODYSSEY prose ALL POINTS NORTH LITTLE GREEN MAN MOON COUNTRY (with Glyn Maxwell) THE WHITE STUFF GIG WALKING HOME The Story of the Iliad A Dramatic Retelling of Homers Epic and the Last Days of Troy SIMON ARMITAGE  Copyright 2014 by Simon Armitage

Copyright 2014 by Simon Armitage

First American Edition 2015 Originally published in Great Britain under the title THE LAST DAYS OF TROY All rights reserved For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to Permissions, Liveright Publishing Corporation,

a division of W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.,

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110 For information about special discounts for bulk purchases, please contact W. W. Norton Special Sales at specialsales@wwnorton.com or 800-233-4830 Production manager: Julia Druskin The Library of Congress has cataloged the printed edition as follows: Armitage, Simon, 1963

[Last days of Troy]

The story of the Iliad : a dramatic retelling of Homers epic and the last days of Troy / Simon Armitage.First American edition

pages cm

Originally published in Great Britain under the title THE LAST DAYS OF TROY.t.p. verso.

ISBN 978-0-87140-890-7 (pbk.)

1.

Trojan WarDrama. 2. Troy (Extinct city)Drama. 3. Epic poetry, GreekAdaptations. I.

Title.

PR6051.R564L37 2015

822.914dc23

2014034515 ISBN 978-0-87140-893-8 (e-book) Liveright Publishing Corporation

500 Fifth Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10110

www.wwnorton.com W. W. Norton & Company Ltd.

Castle House, 75/76 Wells Street, London W1T 3QT INTRODUCTION NOTE: The Story of the Iliad: A Dramatic Retelling of Homers Epic and the Last Days of Troy has been performed under the name of The Last Days of Troy at the Royal Exchange Theatre in Manchester and Shakespeares Globe theatre in London. The accompanying text, The Last Days of Troy , was published by Faber and Faber in May 2014. Homers epic poem the Iliad , written around 700 BCE , begins in the final year of the Trojan War.

Led by Agamemnon, a loose alliance of Greek forces has sailed across the Aegean Sea to bring home Helen, the wife of Menelaus, abducted or seduced by Paris and now living as his wife or concubine within the walled city of Ilium, in the region of Troy. But after almost a decade, an end to the war is nowhere in sight. Infighting and personal enmity between the Greek leaders is threatening to split the coalition apart. Within the besieged city, Trojans are haunted not only by the idea of defeat but by the potential destruction of their civilisation. Even the Gods on Olympus are squabbling among themselves, their favouritism and interventions only prolonging the conflict and exacerbating the misery. Rather than chronicle the entire war, Homer chose to concentrate on a relatively short period of time about fifty days and to focus on relationships and interactions between leading characters on both sides.

Yes, there are big battles, but essentially his is a story which takes us behind the scenes, to what goes on in the tents, corridors, halls and chambers, and beyond the clouds. After some 15,000 lines, the Iliad comes to its enigmatic and poetic conclusion, but at that point we are still no nearer finding out what happened to its leading characters, or who won the war. Some of this information comes to light subsequently through other sources, including Homers Odyssey , in which we are told for the first time how Greek soldiers were smuggled through the impenetrable gates in a wooden horse. But the subject of the last days of Troy is taken up most compellingly by the Roman poet Virgil, over six hundred years later. In Book II of his Aeneid , through the voice of Aeneas, a survivor from Troy, we are given a graphic and intense account of those final hours and of the bloody fates of the defeated. My aim in this dramatisation has been to span those two ancient poems, and present in theatrical form a story that follows the Trojan War through to its bitter end.

The play opens in modern day Hisarlik on the tip of north-west Turkey, the archaeological site of what is widely considered to be the actual geographical location of Troy. To visit the dusty ruins and crumbling walls is to suffer a confusion of information and to experience a tug of war between the heart and the head. Legend and artefact coexist here; fact and fantasy mingle and blur, to the point where its impossible to say where history ends and mythology begins. In relation to the Trojan War this is as true today as it was for Homer, who was writing about events said to have taken place in the Bronze Age, four or five hundred years before he was born. Indeed, even Homers authorship and his very existence are by no means universally accepted. We are dealing with a mystery that has come to us in echoes and whispers from over three thousand years ago.

Ancient fables endure for all kinds of reasons, but their continued relevance to the way we live now plays a major part in their survival. At the time when this play will be premiered, many countries will be marking and commemorating the centenary of the First World War, with images of atrocities and questions of military morality high in peoples minds, just as they were for Homer. Moreover, the channel or strait that runs from the Bosphorus to the Dardanelles or Hellespont continues to symbolise a political, economic, cultural, philosophical and religious fault line between east and west. In that context, the story of Troy is a blueprint for a conflict that rages to this day. Homer was also astute enough to know that although it is armies who go to war it is usually the individual psychologies of their leaders that send their people into battle. Prejudice, pigheadedness, petulance or just a momentary whim can result in the slaughter of millions.

Nothing has changed. If Helen is said to be the face that launched a thousand ships, and if each Greek vessel was crewed by up to two hundred men, and if the Trojan forces were equal in number, as they must have been to ensure a reasonably fair fight, then as well as reducing ten years worth of backstory to two or three hours of performance, I was also faced with the task of reducing over four hundred thousand participants to a cast of about a dozen. So a whole pantheon of gods, with their various allegiances and attributes, are represented through Zeus, Hera and Athene. On the ground, minor characters, parallel narratives and self-contained episodes have been omitted, and some principal characters rolled into one. Odysseus, for example, is an amalgamation of several high-ranking nobles in the Greek encampment, though he still retains (I hope) those personal traits forever associated with him. But challenges often present unanticipated opportunities: Menelaus is an important figure in the original story, but as the play developed I found his absence to be a more useful dramatic device than his presence.

His brother, Agamemnon, must do his bidding, just as the whole Greek army must sail to war on behalf of a cuckold. Other characters and scenes have grown in relation to their original status. Helen, little more than a walk-on part in Homers poem, is pivotal to this version. And at one point I require several thousand Trojan soldiers to surge across no-mans-land, a problem I have left at the door of the director. The Last Days of Troy was commissioned by the Royal Exchange Theatre, Manchester, for production in spring 2014. Further performances were then scheduled at Shakespeares Globe in London via a full stage transfer.

Next page

by the same author poetry ZOOM! XANADU KID BOOK OF MATCHES THE DEAD SEA POEMS CLOUDCUCKOOLAND KILLING TIME SELECTED POEMS TRAVELLING SONGS THE UNIVERSAL HOME DOCTOR TYRANNOSAURUS REX VERSUS THE CORDUROY KID SEEING STARS SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT THE DEATH OF KING ARTHUR drama MISTER HERACLES (after Euripides) JERUSALEM HOMERS ODYSSEY prose ALL POINTS NORTH LITTLE GREEN MAN MOON COUNTRY (with Glyn Maxwell) THE WHITE STUFF GIG WALKING HOME The Story of the Iliad A Dramatic Retelling of Homers Epic and the Last Days of Troy SIMON ARMITAGE

by the same author poetry ZOOM! XANADU KID BOOK OF MATCHES THE DEAD SEA POEMS CLOUDCUCKOOLAND KILLING TIME SELECTED POEMS TRAVELLING SONGS THE UNIVERSAL HOME DOCTOR TYRANNOSAURUS REX VERSUS THE CORDUROY KID SEEING STARS SIR GAWAIN AND THE GREEN KNIGHT THE DEATH OF KING ARTHUR drama MISTER HERACLES (after Euripides) JERUSALEM HOMERS ODYSSEY prose ALL POINTS NORTH LITTLE GREEN MAN MOON COUNTRY (with Glyn Maxwell) THE WHITE STUFF GIG WALKING HOME The Story of the Iliad A Dramatic Retelling of Homers Epic and the Last Days of Troy SIMON ARMITAGE  Copyright 2014 by Simon Armitage

Copyright 2014 by Simon Armitage