For Simon Prosser

Omissions are not accidents.

Marianne Moore, epigraph to The Complete Poems of Marianne Moore

History is not merely what happened; it is what happened in the context of what might have happened.

Hugh Trevor-Roper, History and Imagination

Nobody I know would take advice from Hamlet.

Jennifer Grotz, The Nunnery

Contents

Prologue

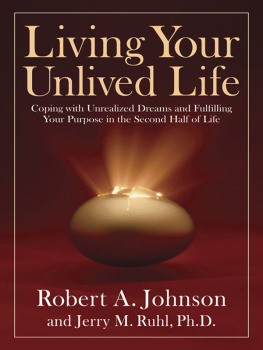

The unexamined life is surely worth living, but is the unlived life worth examining? It seems a strange question until one realizes how much of our so-called mental life is about the lives we are not living, the lives we are missing out on, the lives we could be leading but for some reason are not. What we fantasize about, what we long for, are the experiences, the things and the people that are absent. It is the absence of what we need that makes us think, that makes us cross and sad. We have to be aware of what is missing in our lives even if this often obscures both what we already have and what is actually available because we can survive only if our appetites more or less work for us. Indeed, we have to survive our appetites by making people cooperate with our wanting. We pressurize the world to be there for our benefit. And yet we quickly notice as children it is, perhaps, the first thing we do notice that our needs, like our wishes, are always potentially unmet. Because we are always shadowed by the possibility of not getting what we want, we learn, at best, to ironize our wishes that is, to call our wants wishes: a wish is only a wish until, as we say, it comes true and, at worst, to hate our needs. But we also learn to live somewhere between the lives we have and the lives we would like. This book is about some versions of these double lives we cant help but live.

There is always what will turn out to be the life we led, and the life that accompanied it, the parallel life (or lives) that never actually happened, that we lived in our minds, the wished-for life (or lives): the risks untaken and the opportunities avoided or unprovided. We refer to them as our unlived lives because somewhere we believe that they were open to us; but for some reason and we might spend a great deal of our lived lives trying to find and give the reason they were not possible. And what was not possible all too easily becomes the story of our lives. Indeed, our lived lives might become a protracted mourning for, or an endless tantrum about, the lives we were unable to live. But the exemptions we suffer, whether forced or chosen, make us who we are. As we know more now than ever before about the kinds of lives it is possible to live and affluence has allowed more people than ever before to think of their lives in terms of choices and options we are always haunted by the myth of our potential, of what we might have it in ourselves to be or do. So when we are not thinking, like the character in Randall Jarrells poem, that The ways we miss our lives is life, we are grieving or regretting or resenting our failure to be ourselves as we imagine we could be. We share our lives with the people we have failed to be.

We discover these unlived lives most obviously in our envy of other people, and in the conscious (and unconscious) demands we make on our children to become something that was beyond us. And, of course, in our daily frustrations. Our lives become an elegy to needs unmet and desires sacrificed, to possibilities refused, to roads not taken. The myth of our potential can make of our lives a perpetual falling-short, a continual and continuing loss, a sustained and sometimes sustaining rage; though at its best it lures us into the future, but without letting us wonder why such lures are required (we become promising through the promises made to us). The myth of potential makes mourning and complaining feel like the realest things we ever do; and makes of our frustration a secret life of grudges. Even if we set aside the inevitable questions How would we know if we had realized our potential? Where did we get our picture of this potential from? If we dont have potential what do we have? we cant imagine our lives without the unlived lives they contain. We have an abiding sense, however obscure and obscured, that the lives we do lead are informed by the lives that escape us. That our lives are defined by loss, but loss of what might have been; loss, that is, of things never experienced. Once the next life the better life, the fuller life has to be in this one, we have a considerable task on our hands. Now someone is asking us not only to survive but to flourish, not simply or solely to be good but to make the most of our lives. It is a quite different kind of demand. The story of our lives becomes the story of the lives we were prevented from living.

Darwin showed us that everything in life is vulnerable, ephemeral and without design or God-given purpose. For disillusioned non-believers who, of course, pre-dated Darwin and created the conditions for his work and its reception belief in God (and providential design) was replaced by belief in the infinite untapped talents and ambitions of human beings (and in the limitless resources of the earth). It became the enduring project of our modern cultures of redemption cultures committed above all to science and progress to create societies in which people can realize their potential, in which growth and productivity and opportunity are the watchwords (it is essential to the myth of potential that scarcity is scarcely mentioned: and growth is always possible and expected). And yet, as William Empson wrote in the appropriately entitled Some Versions of Pastoral , it is only in degree that any improvement of society could prevent wastage of human powers; the waste even in a fortunate life, the isolation even of a life rich in intimacy, cannot but be felt deeply, and is the central feeling of tragedy. Our wished-for lives, the lives we miss out on, are at once both an acknowledgement of, and part of our toolkit for dealing with, this unavoidable waste. They are the ways as are the tragedies discussed in this book of thinking about, of transforming, the isolation and the waste.

Because we are nothing special on a par with ants and daffodils it is the work of culture to make us feel special; just as parents need to make their children feel special to help them bear and bear with and hopefully enjoy their insignificance in the larger scheme of things. In this sense growing up is always an undoing of what needed to be done: first, ideally, we are made to feel special; then we are expected to enjoy a world in which we are not. After Darwin we have to work out what, other than specialness, might make our lives worth living; after Darwin we can say, when people realize how accidental they are, they are tempted to think of themselves as chosen. We certainly tend to be more special, if only to ourselves, in our (imaginary) unlived lives.

So it is worth wondering what the need to be special prevents us seeing about ourselves other, that is, than the unfailing transience of our lives; what the need to be special stops us from being. This, essentially, is the question psychoanalysis was invented to address: what kind of pleasures can sustain a creature that is nothing special? Once the promise of immortality, of being chosen, was displaced by the promise of more life the promise, as we say, of getting more out of life the unlived life became a haunting presence in a life legitimated by nothing more than the desire to live it. For modern people, stalked by their choices, the good life is a life lived to the full. We become obsessed, in a new way, by what is missing in our lives; and by what sabotages the pleasures that we seek. Childhood is a problem because of the effect it has on the adults we are able to become. No one has ever had the adolescence they should have had. No one has ever taken enough of their chances, or had enough chances to take, and so on.