Mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities in this book does not imply endorsement by the author or publisher, nor does mention of specific companies, organizations, or authorities imply that they endorse this book, its author, or the publisher. Internet addresses and telephone numbers given in this book were accurate at the time it went to press.

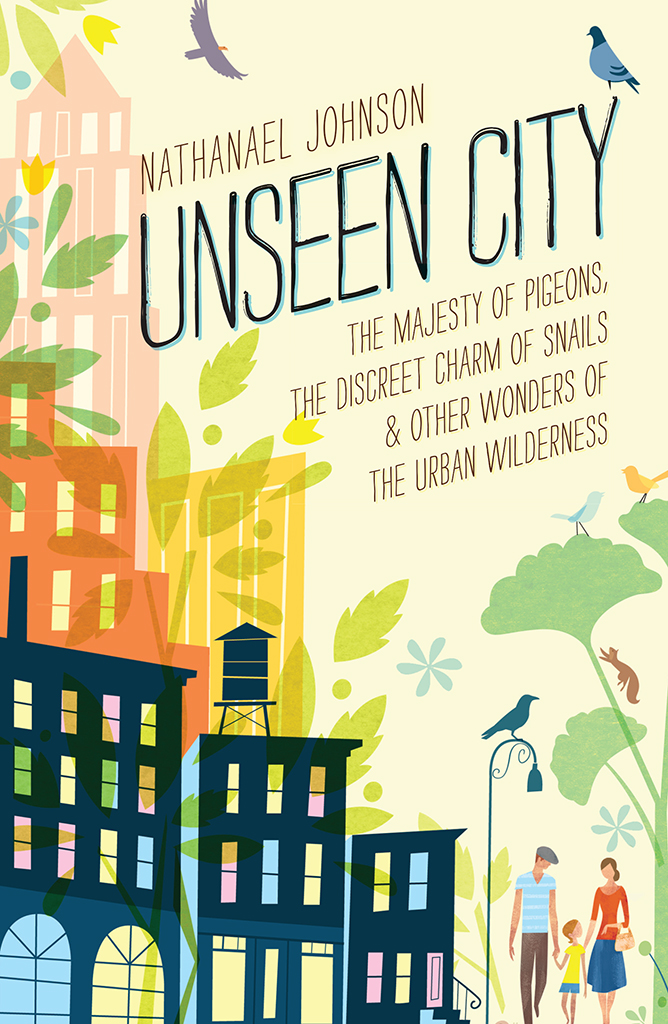

2016 by Nathanael Johnson

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any other information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the publisher.

Chapter icon illustrations by Paige Vickers

Book design by Carol Angstadt

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-62336-385-7 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-62336-386-4 e-book

We inspire and enable people to improve their lives and the world around them.

www.rodalewellness.com

To Beth

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

This whole thing got started because my one-year-old daughter, Josephine, wouldnt stop asking me about the world around us. The book that you are holding is an outgrowth of my attempts to deal with her questions.

Back then, Josephine had vanishingly pale eyebrows and hair that had grown into stylish jags. When she smiled, her eyes turned from thoughtful to impish, her cheeks dimpled, and she exposed the top four of her six teeth. She was just tall enough to clonk her head when she stood up suddenly under a table. She was not yet clever enough to understand the problem, so shed rise vigorously, driving her head into the particleboard. Then she would sit down, wide-eyed but stoic, shift to a slightly different position, and repeat the maneuver. The fontanel of her skull had nearly closed by that time. Id check it periodically as we descended the hill from daycare, she riding in a front pack. Walking two fingers back from her forehead and over the rolling smoothness of her straight blond hair, which smelled like playground sand, Id find good thick skull extending far enough back that Id begin to think it must have closed entirely, and then, under the pad of a forefingeran edge, a terrifying softness.

My every cell ached to protect her, but she did have a few unforgivable flaws. For one thing, shed ask me to name everything she saw. Her favorite word by far was that, usually uttered in a tone both interrogative and imperative. That? she would ask/command, extending an imperious finger. Thats a house, I would say.

That!this time leaning backward in the front pack until I could see only the underside of her chin and her extended arm.

That is the sky.

That!

A tree.

That!

Still a tree.

That.

Yet another tree.

It was one of those awful bargains you find yourself striking as a parent: If you agree not to scream, I will allow you to suck the life out of me with this horrible and stultifying game. And so, after a few weeks, I added a rule to complicate the gameI would give the same answer only once per outing. The second time Josephine inquired about a tree, I would have to be more specific. Trunk, I would say, or leaves, a branch, a twig, a flower. And it was in this way that I noticed for the first time, though Id walked by this tree hundreds of times, that it had tiny yellow flowers. The leaves were long and narrow, dark green on the top and, on the underside, nearly white, spotted with black. At the center of each cluster of leaves were tiny yellow flowers. I picked a few (a difficult task because breaking the supple green branch was like tearing a red licorice rope) and stuffed them in my pocket. Later, when I examined them, I saw that I had come away with about fifteen flowers, each one at a slightly different stage of maturity, revealing the stages of their development in my palm. A clusters flowers started as little green balls that would split and open, the petals of each pushing outward and then opening backward until the five yellow petals had perfectly interdigitated with the five green pieces of the sheath, alternating yellow, green, yellow, green. Orangey hairs tufted in the middle, with a single transparent rod at the exact center. In the next stage of life, this rod rose, carried upward by a bulging green fruit swelling from beneath, the yellow bits now falling away, until finally what was left was a ball about the size of a pea, topped by a spike. I had never seen any of this before.

The next day I put Josephine in the carrier a little early so we could make a one-block detour to the bookstore. There, I bought a used copy of The Trees of San Francisco. My flowers had come, the book told me, from Tristaniopsis laurina. It was one of the most common street trees in the city, and the author noted (uncharitably, I thought, after my intimate examination) that its bloom was semishowy. The name was a bit of a disappointment: I like a name that tells you something of a trees place in the larger scheme of things. To pass a tree and simply register it as a tree is to never really see itand certainly never notice the flowers. To pass a tree and simply register it as T. laurina isnt much betterworse if I memorized the name to inflict Latinate pedantry upon my friends. But knowing a name can also be a first step up a staircase to significance. Tristaniopsis, it turns out, indicates that the species resembles (-opsis means likeness) a shrub first identified by the French botanist Jules M. C. Tristan. Laurina came from the fact that it looked like a laurel tree. I liked this: It was the grittier, tougher Australian version of the Grecian laurel, this one woven into wreaths to crown rugby players and crocodile hunters rather than scholars and Olympians.

The flowers are supposed to emerge between April and June, yet all the treesI had started noticing them everywhere by this pointwere blooming in early November. Were the trees confused by San Franciscos Indian summer? Or did they bloom twice, once in the April warmth and then again in the second summer following Augusts false winter? If they bloomed twice, did that mean that, from the trees perspective, two years had passed, with Earth perhaps tilting faster on this side of the globe, causing it to lay down two rings in its trunk each calendar year? None of the answers were in my book, nor were there any of the stories Id wanted to learn once I began examining the flowers. For whom are these fruits produced for, and how does that relationship work? Was it love, enslavement, a con? I resolved to watch more carefully.

My sudden fascination with the lives of trees wasnt a random result of Josephines That game. There was a reason Id bought a book about trees rather than a book on garage doors or telephone poles, which my daughter inquired about just as often. As a kid, Id known all the trees that grew around my home in the foothills of the Sierra Nevada, and this had given me access to a world otherwise invisible: When I saw a gray pinescraggy branches, curving trunk, and dull, gray-green needlesI knew the earth beneath my feet was laced with serpentinite rock, and very little water. It meant I was at the lower, hotter edge of the Sierras forests. I knew these trees are also called digger pines, after the local Native Americans, whom the white gold miners had dismissed as diggers miserably grubbing for food. The gray pines twisting trunks, in the miners view, were as useless for timber as the native population was for servitude, and the two therefore shared the epithet. What the whites didnt know was that the Indians werent digging around these trees, they were snacking: The pine nuts in their cones are fat and tasty. (It is telling that the prospectorswho could much more aptly be described as diggerschose to mock digging as a sign of baseness.)