Marie Brennan

WITHIN THE SANCTUARY OF WINGS

MEMOIR BY LADY TRENT

Writing the final volume of ones memoirs is a very peculiar experience. This book does not chronicle the end of my life, as I am not yet dead; indeed, I am still hale enough that I hope to enjoy many years to come. It does not even chronicle the end of my career: I have done a great many things since the events described herein, and am rather proud of some of them.

I suspect, however, that any sequelae would inevitably be a disappointment for the reader. Compared with what preceded it, my life in recent decades has been quite sedate. Harrowing experiences have been thin on the ground, the gossip about my personal life has long since grown stale, and although I am very proud of what I have learned about the digestive habits of the so-called meteor dragon of northern Othol, that is not something I expect anyone but a dedicated dragon naturalist to find interesting. (And such individuals, of course, may read my scholarly publications to sate their thirst.) This book is not the conclusion of my tale, but it is the conclusion of a tale: the story of how my interest in dragons led me to the series of discoveries which have made me famous around the world.

For you, my readers, who are already so familiar with the tales conclusion, the version of myself I have presented throughout these memoirs must seem terribly dense and slow of thought. Consider me akin to our ancestors who believed the sun revolved around the earth: I could only reason from the evidence before me, and that evidence was for many years incomplete. It was not until I had the final pieces that I could see the whole; and acquiring those final pieces required a good deal of effort (not to mention peril to life and limb). I have endeavoured here to re-create the world as it seemed to me at the time, without allowing it to be coloured overmuch by current knowledge. For the inevitable inaccuracies and omissions that has entailed, I apologize.

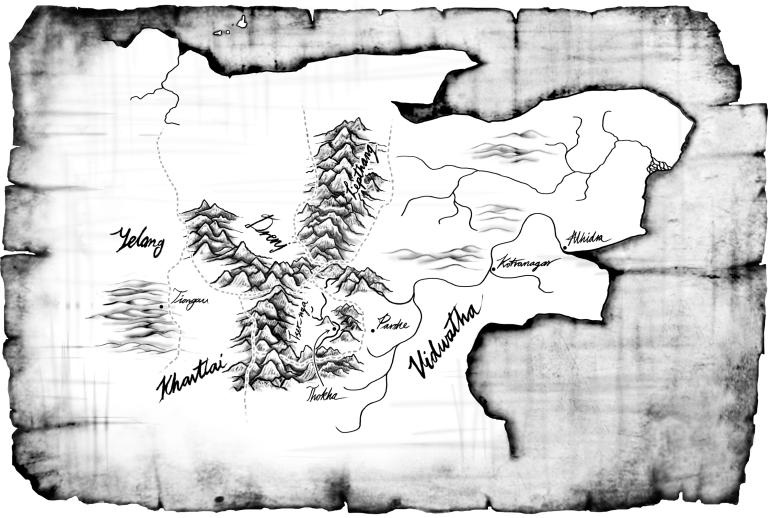

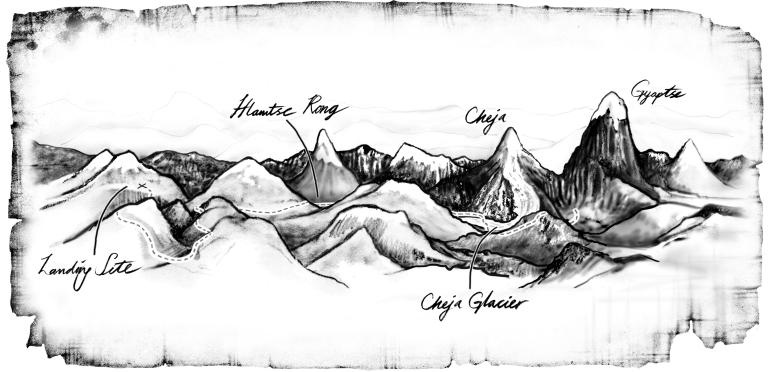

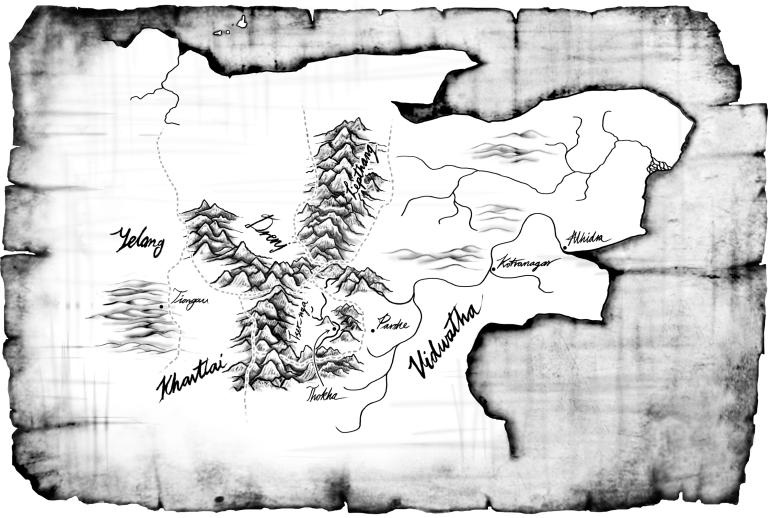

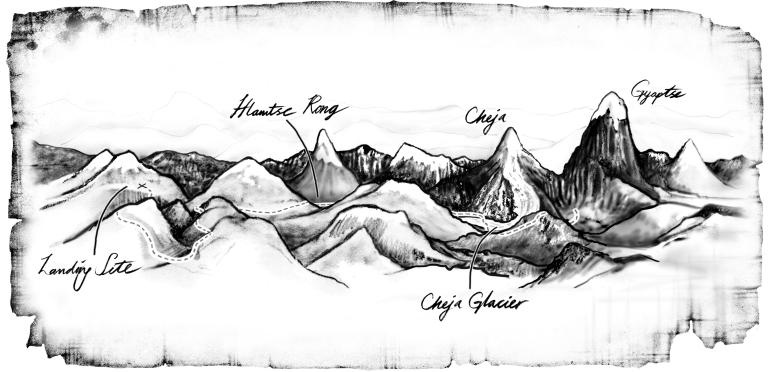

But we must not rush ahead. Before we reach the end of my journey, there is more to be told: the scientific advances of the time; the various conflicts which came to be termed the Aerial War; and the fateful encounter which sent me into the dizzying heights of the Mrtyahaima Mountains. I hope my words may convey to you even a quarter of the sheer astonishment and wonder I experiencedand, perhaps, a fraction of the terror as well. After all, without both sides of that coin, you cannot truly know its worth.

Isabella, Lady TrentCasselthwaite, Linshire10 Ventis, 5662

In which the memoirist acquires a most unexpected allyLife as a ladyA lecture at Caffrey HallMy husbands studentThe state of our knowledgeSuhails theoryA foreign visitorMembers of the peerage, I need hardly tell you, are not always well behaved. Upon my ascension to their ranks, I might have become dissolute, gambling away my wealth in ways ranging from the respectable to quite otherwise. I might have ensconced myself in the social world of the aristocracy, filling my days with visits to the parlours of other ladies and the gossip of fashion and scandal. I might, were I a man, have involved myself in politics, attempting to carve out a place in the entourage of some more influential fellow.

I imagine that by now very few of my readers will be surprised to hear that I eschewed all these things. I have never been inclined to gamble (at least not with my money); I find both fashion and scandal to be tedious in the extreme; and my engagement with politics I have always limited as much as possible.

Of course this does not mean I divorced myself entirely from such matters. It would be more accurate to say I deceived myself: surely, I reasoned, it was not at all political to pursue certain goals. True, I lent my name and support to Lucy Devere, who for years had campaigned tirelessly on behalf of womens suffrage, and I could not pretend anything other than a political motive there. My name carried a certain aura by then, and my support had become a meaningful asset. After all, was I not the renowned Lady Trent, the woman who had won the Battle of Keonga? Had I not marched on Point Miriam with an army of my own when the Ikwunde invaded Bayembe? Had I not unlocked the secrets of the Draconean language, undeciphered since that empires fall?

The answer to all these things, of course, was no. The popular narrative of my life has always outshone the reality by rather a lot. But I was aware of that radiance, and felt obliged to use it when and where I could.

But surely the other uses to which I put it were only scholarly. For example, I helped to found the Trent Academy for Girls in Falchester, educating its students not only in the usual female accomplishments of music and literature, but also in mathematics and various branches of science. When Merritford University began awarding the first degrees in Draconic Studies, I was pleased to endow the Trent Chair for that field. I contributed both monetary and social support to the International Fraternity for Draconic Research, an outgrowth of the work Sir Thomas Wilker and I had begun at Dar al-Tannaneen in Qurrat. Less formally, I encouraged the growth of the Flying University until it formed a network of friendships and lending libraries all across Scirland, catching in its net a great many people who would otherwise not have had access to such educational opportunities.

Such things accumulate, bit by bit, and one does not notice until it is too late that they have eaten ones life whole.

On the day that I went to attend a certain lecture at Caffrey Hall, I was running behind schedule, which had become the common state of my life. Indeed, the only reason I did not miss it entirely was because I had purchased a clock of phenomenal ugliness, whose sole virtuemost would call it a flawwas its intolerably loud chiming. This was the only force capable of rousing me from my haze of letter-writing, for our butler had recently joined the army, our housekeeper had left us to care for her elderly mother, and I was not yet on good enough terms with their replacements to rely on them to evict me from my study by force.

But they had the carriage waiting when I came flying down the stairs, and in short order I was on my way to Caffrey Hall. At the time I was grateful because I would have been sorely disappointed to miss the lecture. In hindsight, I would have missed out on a great deal more.

The crowd on the street outside was large enough that I directed my driver around the corner, where I disembarked and entered the hall by a side entrance. This deposited me much closer to my first port of call, which was a room near the lecture hall proper. I pressed my ear to the door and heard a voice murmuring inside, which warned me not to disturb him by knocking. Instead I eased the door open and slipped quietly through.

Suhail was pacing a narrow circuit across the floor, sheaf of papers in one hand, the other fiddling with the edge of his untied cravat as if it were a headscarf, muttering in a low, quick voice. It was his habit before any lecture to make one final pass through his points. When he saw me, though, he stopped and took out his pocket watch. Is it time?

Not yet, I said. One could not have guessed it by the hubbub, which was audible even through the door. I am dreadfully late, though. There was a new report from Dar al-Tannaneen.