Marie Brennan

WITH FATE CONSPIRE

Home is a name, a word, it is a strong one; stronger than magician ever spoke, or spirit ever answered to, in the strongest conjuration.

Charles Dickens,

Martin Chuzzlewit

The Onyx Hall, London: January 29, 1707

The lights hovered in midair, like a cloud of unearthly fireflies. The corners of the room lay in shadow; all illumination had drawn inward, to this spot before the empty hearth, and the woman who stood there in silence.

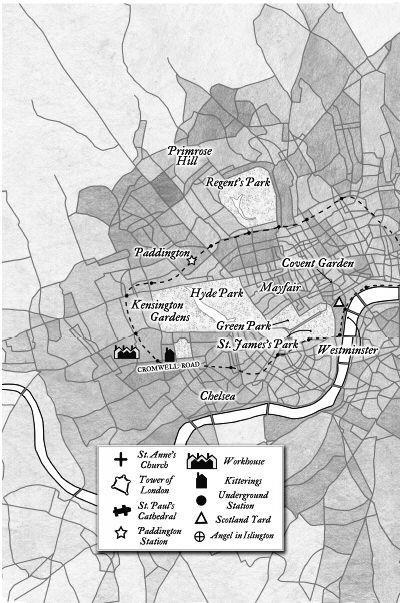

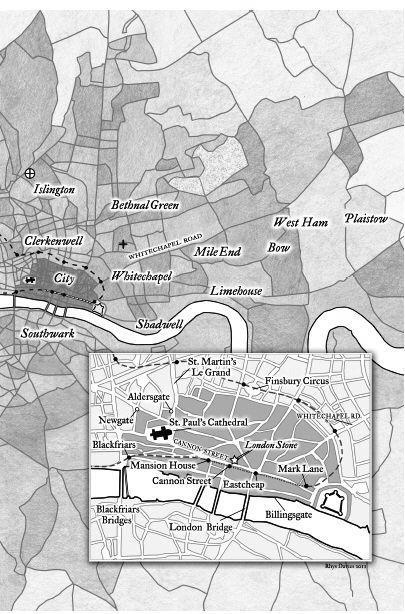

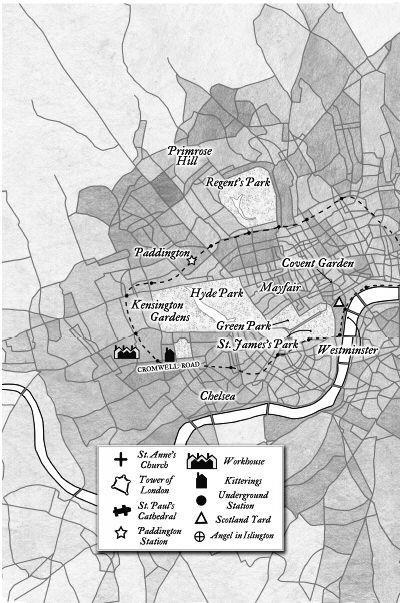

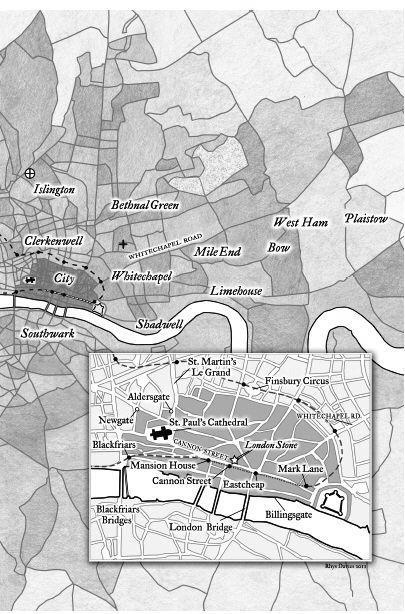

Her right hand moved with absent surety, coaxing the lights into position. The left hung stiff at her side, a rigid claw insufficiently masked by its glove. Without compass or ruler, guided only by bone-deep instinct, she formed the lights into a map. Here, the Tower of London. To the west, the cathedral of St. Pauls. The long line of the Thames below them, and the Walbrook running down from the north to meet it, passing the London Stone on its way; and around the whole, touching the river on both sides, the bent and uneven arc of the city wall.

For a moment it floated before her, brilliant and perfect.

Then her fingertip reached up to a northeastern point on the wall, and flicked a few of the lights away.

As if that had been a summons, the door opened. Only one person in all this place had the right to interrupt her unannounced, and so she stayed where she was, regarding the newly flawed map. Once the door was closed, she spoke, her voice carrying perfectly in the stillness of the room. You were unable to stop them.

Im sorry, Lune. Joseph Winslow came forward, to the edge of the cool light. It gave his ordinary features a peculiar cast; what would have seemed like youth in the brightness of daymore youth than he should claimturned into strange agelessness under such illumination. It is too much in the way. An impediment to carts, riders, carriages, people on foot it serves no purpose anymore. None that I can tell them, at least.

The silver of her eyes reflected blue as she traced the line of the wall. The old Roman and medieval fortification, much patched and altered over the centuries, but still, in its essence, the boundary of old London.

And of her realm, lying hidden below.

She should have seen this coming. Once it became impossible to crowd more people within the confines of London, they began to spill outside the wall. Up the river to Westminster, in great houses along the bank and pestilential tenements behind. Down the river to the shipbuilding yards, where sailors drank away their pay among the warehouses of goods from foreign lands. Across the river in Southwark, and north of the wall in suburbsbut at the heart of it, always, the City of London. And as the years went by, the seven great gates became ever more clogged, until they could not admit the endless rivers of humanity that flowed in and out.

In the hushed tone of a man asking a doctor for what he fears will be bad news, Winslow said, What will this do to the Onyx Hall?

Lune closed her eyes. She did not need them to look at her domain, the faerie palace that stretched beneath the square mile enclosed by the walls. Those black stones might have been her own bones, for a faerie queen ruled by virtue of the bond with her realm. I do not know, she admitted. Fifty years ago, when Parliament commanded General Monck to tear the gates from their hinges, I feared it might harm the Hall. Nothing came of it. Forty years ago, when the Great Fire burned the entrances to this place, and even St. Pauls Cathedral, I feared we might not recover. Those have been rebuilt. But now

Now, the mortals of London proposed to tear down part of the walltear it down, and not replace it. With the gates disabled, the City could no longer protect itself in war; in reality, it had no need to do so. Which made the wall itself little more than a historical curiosity, and an obstruction to Londons growth.

Perhaps the Hall would yet stand, like a table with one of its legs broken away.

Perhaps it would not.

Im sorry, Winslow said again, hating the inadequacy of the words. He was her mortal consort, the Prince of the Stone; it was his privilege and duty to oversee the points at which faerie and mortal London came together. Lune had asked him to prevent the destruction of the wall, and he had failed.

Lunes posture was rarely less than perfect, but somehow she pulled herself even more upright, her shoulders going back to form a line hed come to recognize. It was an impossible task. And perhaps an unnecessary one; the Hall has survived difficulties before. But if some trouble comes of this, then we will surmount it, as we always have.

She presented her arm to him, and he took it, guiding her with formal courtesy from the room. Back to their court, a world of faeries both kind and cruel, and the few mortals who knew of their presence beneath London.

Behind them, alone in the empty room, the lights drifted free once more, the map dissolving into meaningless chaos.

I behold London; a Human awful wonder of God!

William Blake,

Jerusalem: The Emanation of the Giant AlbionOh City! Oh latest Throne! where I was raisd

To be a mystery of loveliness

Unto all eyes, the time is well nigh come

When I must render up this glorious home

To keen Discovery: soon yon brilliant towers

Shall darken with the waving of her wand;

Darken, and shrink and shiver into huts,

Black specks amid a waste of dreary sand,

Low-built, mud-walled, Barbarian settlement,

How changd from this fair City!

Alfred, Lord Tennyson, Timbuctoo

A great town is like a forestthat is not the whole of it that you see above ground.

Mr. Lowe, MP, address at the opening of the Metropolitan Railway, reported in the

Times, January 10, 1863

Given enough time, anything can become familiar enough to be ignored.

Even pain.

The searing nails driven through her flesh ache as they always have, but those aches are known, enumerated, incorporated into her world. If her body is stretched upon a rack, muscles and sinews torn and ragged from the strain, at least no one has stretched it further of late. This is familiar. She can disregard it.

But the unfamiliar, the unpredictable, disrupts that disregard. This new pain is irregular and intense, not the steady torment of before. It is a knife driven into her shoulder, a sudden agony stabbing through her again. And again. And again.

Creeping ever closer to her heart.

Each new thrust awakens all the other pains, every bleeding nerve she had learned to accept. Nothing can be ignored, then. All she can do is endure. And this she does because she has no choice; she has bound herself to this agony, with chains that cannot be broken by any force short of death.

Or, perhaps, salvation.

Like a patient cast down by disease, she waits, and in her lucid moments she prays for a cure. No physician exists who can treat this sickness, but perhapsif she endures long enoughsomeone will teach himself that science, and save her from this terrible death by degrees.

So she hopes, and has hoped for longer than she can recall. But each thrust brings the knife that much closer to her heart.